Nutrients of Concern

Contents

Nutrients of Actual Concern

B12

The scientific consensus is that vegans need to supplement B-12 since it is not generally found in or on plant foods in significant amounts.

"Vegans who do not ingest vitamin B12 supplements were found to be at especially high risk. Vegetarians, especially vegans, should give strong consideration to the use of vitamin B12 supplements to ensure adequate vitamin B12 intake." [1]

"The main finding of this review is that vegetarians develop B12 depletion or deficiency regardless of demographic characteristics, place of residency, age, or type of vegetarian diet. Vegetarians should thus take preventive measures to ensure adequate intake of this vitamin, including regular consumption of supplements containing B12." [2]

"In order to prevent vitamin deficiency due to inadequate dietary intake, there is an urgent need for vegans to incorporate reliable vitamin B12 sources including vitamin B12-fortified foods such as fortified soy and rice beverages, certain breakfast cereals, or vitamin B12 dietary supplements which usually provide high absorption capacities."[3]

Some people therefore use this lack of B-12 as an excuse not to go vegan--and adopting this stance is a mistake (see Where B-12 Comes From, Everybody Needs B-12).

While it is true that many omnivores also show low levels of B-12 (see Everybody Needs B-12) vegans face a higher risk of severe deficiency. While everyone should supplement B-12, every vegan must supplement B-12. Every major vegan advocacy group and health professional endorses this consensus, namely:

The Vegan Society (UK), People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Michael Greger MD, EVA – Ethisch Vegetarisch Alternatief Belgium, Farm Animal Reform Movement (FARM), Portuguese Vegetarian Association (Associação Portuguesa Vegetariana), Vegan Action (US), Vegan Outreach (US), and over a dozen other professionals.[4]

Since animal products usually contain at the very least a tiny amount of B-12 (aside from honey, which contains none), most omnivores reach the minimum B-12 quantity required to function. However, vegans who do not supplement B-12 or regularly eat foods fortified in B-12 risk getting virtually no B-12 at all because no safe and reliable vegan source of B-12 exists, aside from supplementation (see Vegan B-12 Sources). B-12 deficiency can lead to serious health complications like nerve damage if not recognized and treated immediately, especially since high folate consumption can mask the earlier signs of deficiency like megaloblastic anemia.[5][6]

The recommended B-12 dosage for vegans is from 25 - 100 mcg a day, and many vegan supplements meet these requirements. Unless formulated for particular groups with higher B-12 needs, mainstream multivitamin brands tend to have lower levels of B-12. Still, such products may prevent deficiency if combined with regular consumption of food sources fortified in B-12.

Please do not compromise the health benefits of a vegan diet by doing something foolish like neglecting a simple, cheap, safe and reliable supplement.

See recommendations for details.

Everybody Needs B-12

Everybody, vegan and non-vegan (and even ostrovegan), should supplement with vitamin B-12 for optimal health.

While some animal products may be better sources than others, large amounts of meat or other animal products aren't an optimal strategy to obtain good B-12 levels for anybody because none have levels comparable to or as convenient and reliable as vitamins.

As another downside of trying to get the B-12 needed through food sources, there's a consideration to be made that heat degrades B-12, losing 10% to 60% of B-12 depending on how high the temperature is. [7]

Some people may not need to supplement if they get a lot from their diet and have good absorption, but as a water soluble vitamin it's extremely safe, does not promote risk of overdose, and ensures good levels of the vitamin which is necessary for many vital functions from cell division (particularly blood cells) to nerve function. When we compare the risks (which are virtually nil) to the potential benefits for people who have low or marginal status, and consider the very low cost, it's a clear win.

Most people worldwide, including many meat-eaters, show sub-optimal levels (likely under 600 pg/ml, although this is complicated by disagreement and poor information about what optimal is) and a significant number even show borderline deficiency in B-12. Deficiency or borderline deficiency is particularly common in older people (of which up to 20% are deficient by some sources), but marginal status of 148–221 pmol/L (200-300 pg/ml) is also present in 14-16% under the age of 60[8].

Typical non-vegans (at least pre-middle age) can probably get adequate supplementation as a safety net for optimal levels from mainstream multivitamins which complement food sources (40% of adults are already taking multivitamins). Those middle-aged or older may need to take more and/or eat fortified foods. If vegans are relying on the lower doses in multivitamins, they probably also need to combine that with fortified foods in a couple meals during the day. See recommendations for details.

The prevalence of low levels and benefit of supplementation is not likely explained by lower consumption of animal products in modern man, given that the western diet contains a high percentage of calories from animal products (and more frequent consumption) than in apes (under 10% of calories from animal products). The explanation probably comes down to where B-12 ultimately comes from.

Where B-12 Comes From

A common explanation for B-12 deficiency in modern countries is that we are "too clean".

B-12 is not an animal product. Animals can not produce B-12, and neither can plants.

B-12 is only produced by certain bacteria.

Animal products contain some B-12 because the animals ate B-12 in the form of supplements added to their feed, or by way of coprophagy (The only exceptions to this is that some B-12 is produced internally by bacteria in ruminant animals' stomachs, enteric fermentation, but these animals are also often supplemented with B-12).

Those who take supplements (like vegans) are getting the B-12 more directly from bacteria, while omnivores are getting it from animals... which were likely fed supplements, where it came again from bacteria.

Most animal products are not very concentrated sources of B-12. The only exceptions are beef liver, termites, and bivalves. Exceptions like these are not very popular foods for most people.

At under 5% of the diet, and only consumed a few days out of the year, our ancient ancestors (like modern apes) certainly did not consume enough "meat" of the typical kind of reach anywhere near optimal levels of B-12.

If you're looking for the most "natural" source, there are only a few possibilities:

1. It's a possibility that a substantial amount of dietary B-12 for our ancestors came from the practice of eating insects, particularly termites as other apes do. These are relatively rich sources because of the bacteria they use to digest wood, and they are eaten more regularly making them a more viable source in terms of absorption.

2. If the aquatic ape hypothesis is correct (although it's not a hypothesis with a lot of support), bivalves may have supplied our ancestors with their B-12.

3. Or like other wild herbivores including Chimpanzees, gorillas, and other non-ruminant animals, we likely primarily obtained regular B-12 from the practice of coprophagy (not safe, not recommended).

4. Or other environmental contamination, like drinking dirty lake water which may contain adequate B-12 if consumed regularly (although this is quite speculative, and may be unlikely given the number of people in poorer parts of Africa and Asia drinking contaminated water who suffer from B-12 deficiency).

While there's a lot of good to be said for hygiene, the "too clean" hypothesis has some merit when it comes to bacterial vitamins like B-12. If you lived in the jungle and drank dangerously contaminated lake water and practiced coprophagy you might be fine, but like anybody in our modern society (who wisely abstains from coprophagy and drinks clean water) you have at least a good chance of benefiting from B-12 supplementation even if you eat oysters, and if you're full vegan you almost certainly need to find a reliable source to avoid serious risk of potentially life threatening deficiency.

There are a few mythical vegan sources (some clean, some less so), but none have been well substantiated.

Vegan B-12 Sources

Supplementation is a vegan source, produced from bacteria.

It's worth checking for lactose or gelatin in the supplements, but this is rare and they should otherwise be vegan.

That said, if all you can find is non-vegan supplements, you should take those to stay healthy under the medical exemption.

Bacteria is a natural source (in any way it matters), but "natural" plant sources are more complicated, because B-12 is a very complicated molecule and its absorption and use can be affected by other substances.

It's very difficult to tell apart B-12 and B-12 analogues (molecules that look very much like B-12 and show up like B-12). As such, it's common for sources to be reported to contain B-12 when in reality they primarily or almost exclusively contain an analogue. And an analogue may be worse than useless because it could interfere with the absorption of actual B-12 and it could trick a test to make it look like your levels are good enough. The only true test is to reverse deficiency and reach healthy levels of MMA and Homocysteine.

To date, there have been no proven reliable plant sources of active B-12 that would be viable and safe as a source for vegans to correct deficiency (some make deficiency worse, some have had limited effects at improving but not fully correcting it); the only reliable source is supplements derived from bacteria (which is vegan).

Not seaweed: which may contain some B-12 at very low levels, although the adequate levels of consumption would be huge and threaten an iodine overdose.

Not algae: Spirulina contains large amounts of analogues. Chlorella may contain some active B-12, but this is not yet clear and we don't know if it can correct deficiency (it seems like it can not).

Not fermented foods: The bacteria used in fermentation are not the kind that produce B-12.

While not a plant source, not even the trace of soil (feces) on organic vegetables: feces is a source, but you'd need a real mouth-full to get a significant dose of B-12. Wash your vegetables: failing to do so is not a source of B-12, just a source of food poisoning and antibiotic resistant bacteria (if it's manure on them).

Jack Norris of Veganhealth.org has a more extensive breakdown of claimed plant sources and the research into them here: https://veganhealth.org/vitamin-b12/vitamin-b12-plant-foods/

B-12 stores

It's true that some people have large B-12 stores and can go vegan and then wait many years without supplementing, subsisting on their body's stored up B-12 from when they were omnivores.

But consider this: If we know that even most omnivores are borderline deficient, how is it that new vegans would have any reserves to draw from?

The answer: They probably don't.

If you were a regular consumer of beef liver as an omnivore and just went vegan, you may in fact have plenty of B-12 stored up to last you years. But if you ate a typical omnivore diet, you were probably already borderline deficient, or possibly already deficient in B-12. In the latter case, you will have no stores to fall back on, and you should supplement immediately to be safe. Even if you ate a significant amount of liver, B-12 absorption varies by individual and that is no guarantee. There is no test for B-12 storage, so the only guarantee against deficiency is to have a regular and reliable source of B-12.

B-12 Testing

To make matters worse, because of the often high levels of B-12 analogues (fake B-12) in vegan diets from foods like seaweed, a typical B-12 blood test is not reliable. The only reliable test is a test for Methylmalonic Acid levels, which rise as a result of B-12 deficiency. This test is not common and is something you would probably have to pay for out-of-pocket. There's no reason to waste money on a blood test when:

- Supplements are cheaper than the blood test, at pennies a day

- If you have no B-12 source, it's safe to assume your levels will be low or will soon become low as your minimal stores are depleted (there is no test for B-12 storage, and because you won't be testing every week a normal test result could give you a false sense of security).

- Excess B-12 is harmless in most people (it's actually one of the safest vitamins there are). Megadoses (well in excess of that required) may create mild acne-like symptoms, but reducing the dose to a normal level will reverse this. The only known exception is in smokers, covered below here.

If you are supplementing and you want a test for peace of mind, then you can order a MMA test to confirm your supplements are working.

B-12 & cancer

High intake of B-12 supplementation (over 55 mcg a day) in addition to large dietary intake seems to significantly increase risk of lung cancer in smokers.[9]

There's no consistent evidence to suggest this effect applies to non-smokers (due to the much smaller risk non-smokers are at, and small sample size of non-smokers who develop lung cancer), and particularly in never-smokers, but it may also apply to people exposed to very large amounts of second hand smoke and people who have smoked in the recent past (all vulnerable to the same cancers smokers are).

There's also no evidence that supplementation at levels vegans typically take alone without high dietary intake can result in this outcome for vegan smokers, although it is plausible (In one analysis there was no effect in female smokers, who had lower dietary intake of B-12, and there was no association with multivitamin use containing B-12[10]).

There are a couple non-exclusive possibilities for the effect relative to absorption:

1. It may be the overall higher level of B-12 in the blood in general (as a result of good absorption and adequate status)

2. It may be due to shorter term spikes in blood concentration of B-12 after a particularly large absorbed dose (before it has time to be stored away where the cancer has no access to it)

In the former case, without high levels of dietary B-12 the effect would likely only manifest at much higher supplement levels; possibly higher than 100 mcg a day (because proportionally less is absorbed through single supplements than from dietary sources throughout the day), and any dosage with comparable absorption, such as over 1000 mcg twice a week. The lack of correlation in women for some studies may support this, indicating a threshold of B-12 levels that must be passed for the effect to appear.

In the latter case, large supplement doses may be a concern in themselves, particularly twice a week doses which must be larger to provide enough absorbed B-12 for the non-supplementing days. Smaller, more spread-out doses would help facilitate absorption and storage for adequate status without peaks in B-12 concentration speculatively accessible to the cancer cells.

To be clear, B-12 is not believed to *cause* cancer; it is not a carcinogen or a mutagen, and there is no mechanism by which it would be expected to directly increase risk on its own.

Rather, the mechanism of action seems to be that high B-12 status may be protective or nutritive of cancer cells that already exist (caused by the smoking).

Protective effects could come from reducing the effects of the smoke on the cancer (and it would make the most sense if this applies to overall/average blood B-12 levels, with minor spikes in blood B-12 levels not being particularly relevant).

Cigarette smoke is a double edged sword, both causing cancer and killing cancer cells (on balance, it does the former quite a bit more than the latter).

B-12 sequesters and is used in detoxification of one of the main poisons in cigarette smoke, cyanide, which kills cancer. Of course cyanide kills normal cells too and alt-med cyanide therapy can be deadly[11], but some therapies are being developed to target cancer cells with cyanide producing enzymes[12] so this may be a viable treatment in the future.

By this mechanism large amounts of B-12 may be protective of cancer cells from the deadly effects of cigarette smoke while not offering any protection to normal cells from the carcinogenic effects of the smoke, thus increasing risk of cancer development by further dulling the protective edge of the double edged sword of cigarette smoke in cancer development.

It may also be possible that, by deactivating free B-12 in the lungs, cigarette smoke deprives cancer cells of an essential vitamin for growth and cell function. B-12 is needed for methionine production from homocysteine using certain enzymes[13] In the unique high-cyanide environment of the smoker's lung, B-12 may be a limiting factor to growth. In this case, spikes in B-12 may temporarily overcome the effects of the smoke and provide cancer adequate B-12 to grow during the period after high doses.

A combination of these two mechanisms, or others, may be responsible. Either way, it's the combination of the smoke causing cancer and either protective or nutritive effects of the B-12 for the cancer in the unique environment of a smoker's lung, not the B-12 alone, and it only occurs with larger doses and is only correlated with increased cancer risk for primarily smoking-caused cancer types, not in adenocarcinoma (which is less related to smoking)[14].

B-12 Recommendations

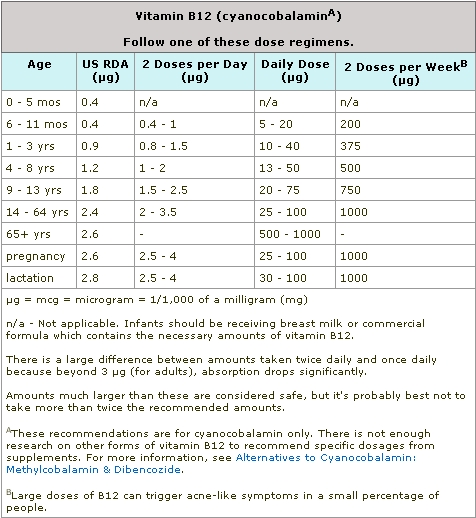

B-12 is more easily absorbed in small amounts, spread out over time. This is because the absorption rate is roughly equivalent to 1.5-2 mcg + 1% of the total amount taken of B12 at a given time before your B12 receptors become saturated. This makes it so that, for example, taking two doses at different times of 5 mcg each is roughly equivalent to taking one dose of 250 mcg.

Jack Norris of Veganhealth.com has a convenient table for reference[15]

If you are supplementing daily, 25-100 mcg is adequate (and can be found in some vegan multivitamins). If you are supplementing only twice a week, you will need 1,000 mcg each time (also a common supplement amount for dedicated B-12 supplements) which averages to almost 300 mcg a day. Larger doses like this slightly increase the risk of minor acne-like side effects, which can be eliminated by taking smaller supplements more frequently.

The science so far is pretty conclusive: the recommended form is cyanocobalamin because it is very stable and reliable. Other forms may be less stable. Cyanocobalamin is also preferred because the body can synthetize it in the two active forms (methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin) on its own. Both methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin are required for different reactions.

If you're looking for cheap, vegan, GMP certified, cyanocobalamin B-12, you can get Solgar's Vitamin B12 1000 mcg (this is an affiliate link, and it helps this site to buy from it).

B-12 is often found in the methylcobalamin form, which doesn't include the adenosylcobalamin form. Adenosylcobalamin is just as essential as methylcobalamin, and the deficiency of it results in an interference with the formation of myelin (nerve health). [16] [17]

That's why supplementing just one of the two active forms would be worse than just getting the cyanocobalamin form.

The trace of cyanide in 100 mcg of B-12 is not harmful, and it is comparable to the natural levels of cyanide in other healthy foods like almonds, but is actually safer than those forms because B-12 binds and neutralizes cyanide preventing acute effect even from huge doses. Even without the B-12, you would need thousands of times the amount to pose a risk (the dose makes the poison).

For those who are deficient or borderline deficient, it is recommended to take a dose of 1000 mcg daily of cyanocobalamin for at least a month [18], before bringing it down to the usual recommended supplementation (while keeping it at 1000 mcg daily for those with pernicious anaemia)--even 500 mcg daily for 2 months wasn't enough to bring poor levels of B-12 back to optimal [19].

B-12 shots are not recommended.

A liquid supplement poses no risk and is suitable for anybody, and pills pose virtually no risk (they can be choking hazards for young children), but a shot can (in a freak accident) hit a nerve and cause serious damage.

Vegans using shots for B-12 also mislead people into thinking they need to get shots to go vegan, and this has been used as a reason not to go vegan (fear of needles is very common).

Please do not get B-12 shots unless ordered by a doctor.

For Smokers

For smokers, the issue is more complicated by the fact that high levels of B-12 supplementation have been correlated with cancer formation as discussed above.

The best recommendation to smokers is this: Stop smoking. It's a recommendation echoed by every major health organization in the world.

But if you will not or can not stop smoking, it may be wise to limit supplementation to 25 mcg a day which would both avoid the blood level spikes and hopefully keep your overall B-12 status high enough to avoid nerve damage but low enough to avoid the increased cancer risk and maintain the likely poisonous effects of cigarette smoke's cyanide on developing cancer cells and/or deny the cancer B-12 for vital functions (whatever the mechanisms may be).

Most B-12 supplements come in larger dosages, so the best option for smokers is probably a multivitamin source (like the vegan society supplement[20]), but otherwise liquid supplements are relatively easy to dilute, and fortified foods (taken regularly and with variety) can be a fairly reliable low-dosage source.

Smokers choosing to limit B-12 supplementation, because of the possible effect of smoking on causing more loss of B-12 and increasing the need for it, might be served by occasional MMA tests to ensure adequate B-12 status, particularly if experiencing symptoms of deficiency.

Vitamin D

This isn't just a vegan issue, everybody needs Vitamin D. While it is true that your body can make it from sunlight pretty easily IF you get enough direct and intense sunlight, sun based production has a few serious drawbacks in terms of safety and reliability:

- Skin Cancer Risk

"Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States.1-2"

While it is possible that some dietary factors (like eating more vegetables) may slightly reduce skin cancer risk, being vegan alone, or any dietary measure (including a tomato only diet to maximize lycopene) is not a reliable way to protect you from skin cancer.

"Current estimates are that one in five Americans will develop skin cancer in their lifetime.3-4"

-American Academy of Dermatology[21]

"Because exposure to UV light is the most preventable risk factor for all skin cancers,6 the American Academy of Dermatology encourages everyone to protect their skin from the sun’s harmful UV rays by seeking shade, wearing protective clothing and using a sunscreen with a Sun Protection Factor of 30 or higher."

- Darker Skin Produces Less, as does wearing sunscreen (as recommended to prevent skin cancer)

To be clear, if you're out in the sun for more than a few minutes, particularly in the summer, and you have light skin you should be using sunscreen (a physical zinc-based sunscreen is probably optimal, since chemical sunscreens have to be reapplied every couple hours). BUT sunscreen does in theory limit vitamin D production by blocking UVB rays (in practice, people out in the sun for a long time will probably still produce enough). There's no way to completely cheat the system here; if you're producing adequate vitamin D from the sun, you're also increasing your risk of skin cancer. - Low UV regions and times of the year can lead to inadequate production.

High Latitudes, Winter, and cloudy seasons are all issues. Air pollution is even an issue (it scatters and absorbs UVB). When attempting to get adequate vitamin D production from the sun, it's important to know the UV index, and this can be hard to keep track of. Some days you may literally need to spend hours outside, or for some people, you may need more hours of sunlight than the day is long. Your needs and the ability of the sun in your area to meet them are not easy to predict.

This is not a unique issue for vegans, most animal products "naturally" contain very little vitamin D. However, some common non-vegan products on the market like cow milk and some breakfast cereals are often fortified with added vitamin D3 (usually animal based), and vegans don't always drink fortified plant milks or eat fortified cereal. Because of this, vegans can be at a higher risk for low vitamin D levels if they do not supplement or get adequate sun exposure for their skin types, which can result in a feeling of being generally unwell/having low energy even in levels below clinical deficiency.

There is one vegan food that can contain vitamin D without being fortified: UV exposed mushrooms. However, this is not likely to be a practical or reliable source for most people. Not only are they inordinately expensive as a vitamin D source, but it's not clear how much vitamin D is going to be present in the mushrooms due to type, duration of exposure, and how long it has been since the mushrooms were exposed and the storage conditions. It's also not clear how well the vitamin D in mushrooms would be absorbed since it may depend on other variables like food preparation and even how well you chew your food.

Oysters are also a source of vitamin D for ostrovegans, but come with many of the same issues as mushrooms in terms of variability.

The cheapest and most reliable source is supplementation.

Most multivitamins are a good option. Vegan multivitamins usually contain D2, which is an adequate source.

Vitamin D2 is plant based. Vitamin D3 is usually derived from lanolin, or sheep wool grease. There is vegan D3 on the market derived from lichen, but it's not used in any fortified foods yet.

Animal derived vitamin D3 in food or supplements is probably an issue of least concern in terms of animal welfare. See trace animal products and byproducts. If you can only find non-vegan vitamin D3, remember this is a tiny trace of animal derived ingredient; it would be better to take this and otherwise stay vegan, and be a healthy vegan, rather than not take it and feel bad risking recidivism or ill health (you can't do much to help the animals if you aren't healthy).

If you already get ample sun exposure due to your current lifestyle, check your local UV index against your skin type: you probably don't need to supplement vitamin D, although it would still be a good idea to start reducing sun exposure, wearing more sunscreen, and supplementing instead if that is an option for you. If you do not get much sun exposure, it would be ill advised to go out of your way to get more sun exposure for vitamin D production when supplements are easier and safer.

The recommended daily supplement dose of vitamin D3 is 2000 UI, which is a safe amount, as lower doses seem to be insufficient for keeping optimal levels long-term. [22]

Iodine

Iodine deficiency is rare in the developed world due to access to iodized salt, and vegans who regularly consume iodized salt are at no greater risk than anybody else. The recommended amount of daily iodine intake is 150 mcg (micrograms) for most adults. This is a fairly easy threshold to reach with iodized salt. 3 grams of iodized salt would roughly give you the recommended daily intake of iodine already.

Processed foods, however, typically do not contain iodized salt. On the other side of the spectrum, unfortunately, some health and natural food trends which correlate with veganism have caused certain consumer groups to reject iodized salt (or even virtually eliminate salt consumption entirely). For vegans, this can be a bigger problem because dairy (in a large part due to iodine-based disinfectants used on the udders) and sea food are often sources of iodine for omnivores, and some vegetables contain iodine antagonists which impair absorption of iodine, thus increasing need for iodine.

It is possible for vegans to get enough iodine from sea vegetables like nori, dulce, etc. However, the amount of iodine present in these foods varies wildly from species to species, and likely even between different crops and regions. Sea vegetables as a major source present the risk of either getting too little or too much [23] due to that variability, and due to ocean contamination may also contain heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and arsenic. Especially when it comes to kelp, the levels of iodine get dangerously high - so high that even eating a small amount of kelp may pass the threshold of the upper safe intake of iodine. [24] It is therefore recommended to avoid eating kelp altogether.

Iodine deficiency in adults causes abnormal thyroid function and goiter, but so can excess iodine. With corrected iodine consumption, goiter (if caused by this) will usually reduce on its own.

In pregnant women, deficiency can result in mental retardation of the child among other developmental problems; these are permanent, so adequate iodine levels are essential in pregnancy.

Iodized salt, or a potassium iodide supplement (alone or as part of a multi) is the safest and most reliable source. However, if your supplement contains iodine from kelp there is probably no reason to worry, due to the small amount.

Outside the developed world, iodine is a bigger concern, roughly 30% of the world's population is iodine deficient[25] due to inadequate access to iodized salt or inconsistent salt iodization legislation. If your country lacks iodized salt, supplementation is probably the only viable option.

All things considered, if you don't have access to iodized salt (or don't consume salt at all, in which case you'd still have to consume sodium through other things like miso), and if you don't regularly eat an adequate amount of seaweed with safe amounts of iodine, then it's strongly recommended to take a daily supplement of 150 mcg of iodine (preferably potassium iodide).

Omega 3, EPA & DHA

EPA and DHA are long-chain forms of Omega-3 fatty acids. The body is able to convert a part of ALA (the easy to get, short-chain form of Omega-3) into EPA and DHA, albeit very inefficiently. EPA and DHA have been found to be protective against brain matter loss from aging and to be preserving of brain functions. [26] , [27] , [28]

Omega-3 ALA can be obtained from whole-plant sources, like walnuts, hempseeds, chiaseeds, flax seeds, and kidney beans. Approximately 8% and 21% of ALA is converted to EPA, respectively for young men and young women, and no more than 4% (men) to 9% (women) converted to DHA. [29] , [30] This conversion rate would make getting the recommended amount of EPA and DHA to preserve brain functions seem complicated. In fact, research suggests that both vegans and omnivores that do not supplement may be falling under the required amount to have preventive effects - as both probably do not regularly eat sources of EPA/DHA, like fish and algae. [31]

The study also shows that to get people with a low index of DHA to be past the threshold where the preventive effects take place, the amount of supplementation required is 250 mg of EPA/DHA.

However, considering the lower end of the spectrum of the conversion rate and the amount of EPA/DHA required, the following daily consumption of ALA-rich foods should be safe:

3 tablespoons (21g) of flax seeds (2g of ALA per tablespoon * 3 tablespoons * 0.04 conversion rate for young men = 240mg DHA)

OR

70g of walnuts (roughly 9% of walnuts are ALA * 70g * 0.04 conversion rate for young men = 252mg DHA)

OR

35g of chia seeds (roughly 18% of chia seeds are ALA * 35g * 0.04 conversion rate for young men = 252mg DHA)

Still, these conversion rates are subjective, as they vary from person to person depending on their genetics and age - and the conversion rate from ALA to DHA for young males can fall below 4%.

As such, unless eating a high amount of ALA from food sources daily and *not being of old age*, or unless eating seaweed daily (which would have to be planned for not exceeding the upper safe limit of iodine intake), it would be preferable to take daily supplements of 250 mg of EPA/DHA from vegan sources.

There are a couple caveats:

- You have to avoid getting too much Omega-6 in your diet, because an excess can interfere with ALA conversion. A 1 to 4 (1:4) ratio of Omega-3 to Omega-6 is often recommended, although the ideal ratio is not known. Trying to maintain this 1:4 (or more Omega-3, up to a 1:1 ratio) is a good idea if you are not supplementing EPA/DHA.

- Pregnant women and infants are very strongly recommended to supplement - as EPA/DHA may be important for brain health in infants - and it’d be beneficial to supplement if you’re young. Infant formulas are supplemented with EPA/DHA to promote a healthy level of Omega-3.

- ALA conversion in older people (after middle age) can be very poor, so it is somewhat strongly recommended to supplement after middle age, while strongly recommended to supplement EPA/DHA later in life.

All in all, taking a supplement of EPA/DHA could range from having some benefits if you’re a young adult, to having significant benefits if you’re old, as it is harmless to take. The only drawback is the cost of the supplements and the fishy aftertaste of some brands (even algae based supplements have this taste), but because the price has dropped significantly for vegan DHA supplements these are likely to be cheaper than regularly consuming fish that contain it (unlike farm grown fish such as tilapia which lack it because they're fed on corn rather than algae where the fatty acids originate).

If you do supplement EPA/DHA, only supplementing DHA should be adequate because it is readily converted into EPA, as the body can effect this conversion much more easily than with the Omega-3 ALA to EPA/DHA conversion.

Calcium

There's a long-standing myth that vegans need less calcium than meat-eaters, because the acidification of animal products during digestion leeches calcium from the bones.

This isn't true, the calcium excreted by meat-eaters in studies was consumed from the meat (it didn't come from the bones).

However, it may be true that calcium needs are just not that high period [32], since we excrete most of what we eat and the body upregulates and downregulates absorption based on need.

For vegans, calcium can be obtained from whole plant sources like dark leafy greens, and particularly collards. Most beans and legumes are also comparatively rich in calcium against grains.

However, the U.S. RDI for calcium is abnormally high and can be hard for vegans to meet unless they really love eating a lot of leafy vegetables (likely too high to reach with beans alone), so for many vegans supplementation can be convenient if attempting to reach the RDI. Fortified plant milks, and even calcium based antacids are good convenient sources (the latter is available world-wide and very cheap).

Tahini is often referenced as a source of calcium for vegans, and this can be true, but it only applies to unhulled tahini (including the shell) which is more bitter and not widely available. Mistakenly relying on hulled tahini for calcium (which has virtually none) could be dangerous, so tahini is not a good recommendation since it's unreliable.

That said, it may not be a concern at all, because the U.S. RDI is unnecessarily high. While we do not like to contradict the U.S. RDI, in this case there seems to be little evidence for it, and RDI in other countries tends to be lower. In the UK it is 700 mg, which is much easier for vegans to meet with a sensible amount of vegetables and legumes. There's reason to believe this is perfectly adequate for adults (although growing teens may need more), bone health is much more dependent on good sources of Vitamin D and exercise than upon calcium consumption beyond a certain point.

Recent studies report that levels as low as 500 mg a day are probably adequate for bone health, and when it comes to cardiovascular mortality the optimal level may be around 800 mg, with a U shaped curve of higher mortality at both very high and very low consumption, although we don't know if this is causal. Recent recommendations for those with oseoporosis are to focus on weight management and exercise instead of calcium supplementation[33].

It's unlikely that a typical vegan diet would reach such low levels (under 500) unless focused on grains to the exclusion of beans and vegetables, so depending on your diet, calcium supplementation may be unnecessary unless you're pregnant, breast feeding, or a growing teen (or possibly over 50 if you're a woman, or over 70 if a man).

Beyond basic needs for bone health, calcium is a complicated topic because there are both protective and harmful correlations with various diseases (reduced risk of some cancers, reduced and increased risk for heart disease), and the mechanisms of action for calcium on those diseases are not at all clear, and frequently contradicted by better evidence. For example, with respect to calcium's involvement in coronary artery calcium (CAC) levels (a risk factor for heart disease) neither supplementation nor circulating calcium has been demonstrated to cause higher levels CAC. In a placebo controlled study 1,000 mg a day calcium carbonate with Vitamin D didn't affect CAC [34].

Some studies generated concern that large amounts of calcium could be correlated with heart disease risk, but recent meta-analyses suggest this only occurs with large amounts (up to around 2 to 2.5 grams a day) [35], and those correlations are poorly controlled and very likely due to mutual causes of heart disease and osteoporosis (like obesity and little exercise), where the osteoporosis prompts people to supplement for calcium and giving the appearance of a correlation with heart disease[36].

Until more information on optimal levels is available, minimum calcium intake probably isn't a concern for vegans eating a varied diet including ample beans and vegetables, but it may be good to assure with a nutrient tracking application that you're getting at least 700 mg (and more if a teen, or pregnant/breast feeding). Likewise, unless a credible mechanism is demonstrated by evidence to differentiate dietary and supplemental calcium, supplemental calcium from plant milks is also not likely a health issue unless eating very large amounts (as mentioned above). As far as the evidence goes, it's probably perfectly safe in moderate amounts, and there's no reason to believe it poses a cardiovascular health risk. If you want to meet or even slightly exceed the U.S. RDI, there should be no risk in doing so.

The largest evidence based danger (where the mechanism of action is known) of calcium consumption is in neutralizing stomach acid and making it more difficult to absorb minerals like iron, which are absorbed best in more acidic stomach conditions. This has less to do with the amount eaten, as which forms and when they are eating (since most supplemental calcium, like from plant milks, are alkaline). It would be a good idea, particularly if you're struggling with iron and other minerals, to consume your supplemental calcium (if you eat it, from plant milks or other added sources) at different meals from your primary iron source.

Zinc

Zinc is mainly an issue for vegans who eat low fat or low protein diets. In protein and fat rich foods like legumes and nuts, zinc is a pretty prevalent mineral and at least for women hard not to get enough of if eating appropriate amounts of these.

For men it may be more difficult since Zinc is exhausted in seminal fluid, so a modest supplement, or a focus on eating more pumpkin seeds and other rich sources, may be a good idea.

If you're eating a varied diet rich in plant proteins and fats from mostly whole food sources, check some sample days in a nutrition tracking app and see if you're meeting the RDA of 11 mg for men and 8 for women (you probably are, or at least close). If you are, supplementation is probably unnecessary. While phytates can bind zinc, it's very likely that most people will adapt and upregulate absorption to compensate.

For those with complexion problems, Zinc is also one of the only supplements with good evidence of efficacy (in modest doses) for improving skin.[37] Problems may indicate poor Zinc status and suggest using a modest supplement or paying more attention to zinc intake.[38] Precaution should be used, because Zinc supplements are not without risk. Remember that the tolerable upper intake for Zinc is 40 mg/day. [39]

Iron

Iron is not typically an issue for vegans or vegetarians. While vegetarians and vegans do often have slightly lower iron stores, they do not have such low levels that they are deficient or develop iron-deficient anemia more often than average meat-eaters.

"Although it is clear that vegetarians have lower iron stores, adverse health effects from lower iron and zinc absorption have not been demonstrated with varied vegetarian diets in developed countries, and moderately lower iron stores have even been hypothesized to reduce the risk of chronic diseases."[40]

Additionally, lower iron stores (without anemia) can be a good thing in the developed world when there is little to no risk of famine (particularly with the risk of antibiotic resistant "superbugs"), as it likely reduces the risk of infection: sequestering iron is one of the primary means multi-cellular organisms defend against pathogens, since iron is necessary for bacterial growth. Speculatively, this may be the best explanation for anecdotal reports of improved immunity in vegetarians and vegans; that the immune system is not stronger, but that bacterial invaders find more hostile conditions because they're deprived of readily available iron. High iron levels are also associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes, and seem to reduce insulin sensitivity, so this could also explain the lower incidence of type two diabetes among vegetarians (Jack Norris discusses this briefly here[41]). Finally, it's not directly related to iron stores, but heme iron (the form of iron in meat) is itself carcinogenic, and one of the prime culprits for the increased risk of colorectal cancer among meat eaters[42].

It's ironic that the excuse many people give for continuing to eat meat (iron) could be one of the main benefits of a vegetarian or vegan diet [43].

In terms of getting enough iron, as long as calcium supplements (which decrease stomach acid) and inhibiting beverages (like coffee and tea [44] , [45]) are avoided at meal-times, iron is easily obtained from plant sources, and particularly if you're eating enough protein from whole plant foods. Consuming vitamin C with an iron rich meal can also help with absorption, and is probably more practical than simply consuming more iron (unless you're consuming very little). The richest plant sources of iron are lentils and dark leafy greens, but most beans and vegetables are good sources. Fortified cereals are also rich sources.

Plant foods are only non-heme iron, and animal products are a mix of both, with a prevalence of non-heme iron--animal products have an average of 40-45% heme iron, and 55-60% non-heme iron.

Non-heme iron is absorbed at a lower rate than heme iron:

"The initial uptake and absorption of nonheme iron were 11% and 7%, respectively, and the absorption of heme iron was 15%." [46]

"Depending on an individual's iron stores, 15% to 35% of heme iron is absorbed. Food contains more nonheme iron and, thus, it makes the larger contribution to the body's iron pool despite its lower absorption rate of 2% to 20%." [47]

So, in the first study it would average to 9% absorption rate for non-heme, and 15% absorption rate for heme; while in the second, it would average to be 11% and 25% respectively.

To understand how the absorption rate of iron between plant foods and animal products differs, let's take into consideration the second study with a bigger difference between the two, for the sake of playing it safe.

We also know that animal products average to be 57.5% non-heme, and 42.5% heme. We can therefore understand that iron sourced from animal products has an average absorption rate of 17%: that is, (57.5% non-heme * 11%) + (42.5% heme * 25%) = 17%.

Meanwhile, plants are 100% heme iron, thus 11% (100% non-heme * 11% = 11%).

These two numbers mean that when trying to understand how much more iron you should get on a plant-based diet compared to someone exclusively eating animal products, it is 1.55 times more (17% / 11% = 1.55).

When compared to an omnivorous diet, it would be even less than 1.55 times higher, as an omnivorous diet would include plant food too--thus, even more non-heme iron (lower absorption) than a 100% animal products diet (which is not realistic).

For the sake of comparison, let's say an omnivorous diet would have half the iron from animal products, and half the iron from plant sources. That would mean that half the iron would be a composition of 57.5% non-heme and 42.5% heme, and the other half iron would be 100% non-heme (plant foods): for a totality of 21.25% heme iron, and 78.75% non-heme.

Therefore, and omnivorous diet whose iron is sourced half from animal products and half from plants, would result in an absorption rate of (78.75% non-heme * 11%) + (21.25% heme * 25%) = about 14%.

When that is compared with a wholly plant-based diet, 14% is not much different from 11%.

In fact, to understand how much more iron you should get on a plant-based diet to match someone on an omnivorous diet (50/50 iron animals/plants), it is 1.27 times more (14% / 11% = 1.27).

All of this is not considering that, as the study says, non-heme iron absorption is markedly influenced by the levels of iron stores and dietary components you eat it with (such as vitamin C), so if low on iron stores and/or consuming vitamin C alongside iron rich-foods consistently, the absorption rate of non-heme iron might be similar to or even surpass that of heme iron. Acidic foods eaten alongside iron-rich foods will result in a very significant increase of the bioavailability of non-heme iron.

For example,

"adding hydrochloric acid to a solution of ferric chloride increased iron absorption more than fourfold, but had no effect on heme iron absorption" [48]

Another two factors to consider when it comes to iron absorption are that fiber intake decreases absorption, and animal protein may increase it. However, it is also reasonable to believe that these two factors would already be accounted for in the results of the studies, as non-heme would be fed through fiber-rich (plant) food, and heme protein would be fed through animal-protein foods, thus the difference in absorption would already be present in the %absorption rate results (unless iron absorption would be measured in a solution without any added food, in which case the absorption could be compared to the various nutrients when eating iron-rich foods instead, or compared to other solutions with added iron and a specific food component that wants to be studied, and conclusions could be drawn as to what makes iron be absorbed less or more and by how much--similarly to vitamin C and acidic foods).

For men, iron deficiency is rarely an issue because needs are much lower. It is occasionally an issue for pre-menopausal women due to monthly iron loss through bleeding. If you have heavy periods, paying close attention to your iron consumption and focusing on lentils and other good iron sources with Vitamin C will likely be adequate. If not, or if you suffer food aversions that make this difficult, a modest iron supplement may be helpful; however, you should talk to your doctor to ascertain that you are in fact low in iron before taking anything more significant than a multivitamin. Iron supplements can be dangerous; while the body will down-regulate absorption from dietary iron and when iron stores are high, a sudden dose via supplement that your body isn't used to can be over-absorbed since your body doesn't have time to down-regulate absorption.

If you do need to supplement, iron can upset the stomach, so following your doctor's dosing advice but spacing out the supplement throughout the day may help with toleration.

Alternatively, wheatgrass powder is an amazing whole-food source of iron, with just 2 tablespoons of it containing roughly up to 14 mg of iron, depending on the brand (as much as you would find in some multivitamins containing iron supplement). Wheatgrass powder goes well in smoothies, where the iron would also be well absorbed thanks to the vitamin C from fruits in the smoothie.

The drawback is the cost of the powder, as the availability of it differs from country to country.

Heme Iron

If you're vegan, you may have heard that the animal based iron (heme) is "better" than the plant based version of iron (non-heme).

The reason that is usually given for this assertion, is heme iron has higher absorption and bioavailability than the plant based non-heme.

And since meats (including red and processed meat) are the highest sources of heme iron, they are usually recommended. The argument, is sometimes used for why you should not be vegetarian/vegan.

If we roughly translate the argument to propositional logic, we get the following:

P1- if X food has heme iron, it is more absorbable than X food with non-heme iron (P⇒Q)P2- If x food is more absorbable than non-heme iron, then it is preferable to non-heme iron (Q⇒R)

C- Therefore, if X food has heme iron, it is preferable to X food with non-heme iron (∴P⇒R)

P⇒Q Q⇒R ∴P⇒R

While this argument is deductively valid there are glaring issues...

P2 doesn’t follow, since even if heme iron is more absorbable, it doesn’t follow from that that it will be preferable to non heme iron in overall health outcomes (total mortality or morbidity metrics)

Therefore, simply looking at absorption can't tell us anything about whether heme iron is actually a better choice for health.

As for P1, it's true that the heme form of iron in animal products is more easily absorbed for most people, but this is irrelevant unless the diet is very low in total iron (this is important in the developing world where malnutrition is common). Most vegans in the developed world eat more than enough to make up for this, because iron absorption is upregulated substantially when stores are low.

Incidentally, Heme iron can not be meaningfully upregulated due to its mechanisms of absorption, and as such is functionally useless at quickly resolving anemia (which is the one thing one might expect it to be able to do fundamentally better than non-heme iron). The proper treatment for iron deficient anemia is non-heme iron supplementation, NOT red meat. Beyond that, the diet should be corrected to introduce more iron rich plant foods, and fortified foods like breakfast cereals, along with vitamin C sources.

There is no plausible reason anybody in the developed world should need to consume heme iron specifically, and due to the carcinogenicity[49] and the difficulty the body has with down-regulating it, it's arguably the worst possible source of iron and only makes sense for people who have no other viable options.

While there may be significant genetic differences for other nutrients' absorption and synthesis, iron is absorbed via a protein called DMT1 (Divalent metal transporter 1), and not only is a deficiency in this incredibly rare (less than one in a million with the genetic mutation, which would be diagnosed in infancy), it also has significant metabolic consequences which are NOT treated with a red-meat rich diet, but rather with transfusions or erythropoietin along with oral iron supplementation[50].

If you are suffering from anemia and your doctor prescribed red meat and will not listen to your objections and give you advice on supplementation, you should try to find another (more competent) doctor who will consider your wishes.

Vitamin A

Your body converts alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, and beta-cryptoxanthin into vitamin A, but the efficiency is low so large doses are needed.

Alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, and beta-cryptoxanthin are provitamin A carotenoids (meaning that they can be converted to retinol), while lutein, zeaxanthin, and lycopene are non-provitamin A carotenoids (meaning that they cannot be converted to retinol). [51]

Consensus of provitamin A carotenoids conversion efficiency is as follows: [52]

- mcg alpha-carotene 24 : 1 mcg RAE (1000 mcg alpha-carotene = 41.7 mcg RAE)

- mcg beta-carotene 12 : 1 mcg RAE (1000 mcg beta-carotene = 83.3 mcg RAE)

- mcg beta-cryptoxanthin 24 : 1 mcg RAE (1000 mcg beta-cryptoxanthin = 41.7 mcg RAE)

RAE (retinol activity equivalent) is a measure of the amount of vitamin A that can be actively absorbed by the body. This is an important unit in the case of vitamin A, because it standardizes the different and low absorption values of the provitamin A carotenoids, and expresses the amount of carotenoids into what their converted retinol quantity would be.

1 mcg RAE = 1 mcg retinol, hence the term 'equivalent'.

RAE = (preformed retinol * 1) + (alpha-carotene / 24) + (beta-carotene / 12) + (beta-cryptoxanthin / 24)

The daily value for RAE is 900 mcg and 700 mcg, respectively for men and women. [53]

Vitamin A is commonly expressed in IU instead of mcg. To know how much IU of vitamin A you're getting, 1 mcg RAE/retinol = 3.33 IU vitamin A.

It's important to follow RAE quantities, or to mathematically convert the carotenoids (following the conversion rate written above) to understand the actual quantity of vitamin A you're absorbing (1 mcg of RAE/retinol would be 3.33 IU of vitamin A).

You can overdose on preformed vitamin A, but not on dietary carotene sources because your body will not poison itself by over-converting (worse case, your skin can become temporarily orange if you eat huge amounts).

Vitamin A in the form of beta-carotene is easily obtained from some specific carotene rich plant foods like carrots, sweet potatoes, pumpkin and spinach. It's much better to use pre-cooked boiled spinach instead of raw, to avoid excessive amounts of oxalate [54]. Beta-carotene is otherwise very difficult to find in concentrated sources in other foods. Leafy vegetables are also a source, but only if consumed in very large amounts (which most people won't do).

Most other vegan staples like grains and legumes are poor sources, so it's important to consume rich sources daily for optimal health. Some plant milks are also fortified with Vitamin A, and most multivitamins contain it. This is not necessary, but can be convenient if you don't want to worry about eating carrots/sweet potato/pumpkin/cooked spinach every day.

Nutrients of Marginal concern

Protein

It's very easy to get enough protein overall on a vegan diet to avoid clinical deficiency, and it is true that it's difficult to become clinically deficient on a mostly whole foods diet unless not eating enough calories or getting the vast majority of calories from starches and sweet fruit (or on a less whole foods diet by consuming processed foods high in starch, sugar and oil).

However, for vegans not eating legumes, particularly if on relatively high-carb diets, it can be easy to get inadequate amounts of lysine. It may not put you in the hospital, but it can make you look and feel terrible.

Lysine is an essential amino acid, and not getting quite enough of it can have serious consequences to hair, skin, bone-health, muscle function, and immune system.

Luckily, this is relatively easy to fix with some dietary changes.

1. Increasing overall protein to around 80 grams will usually fill the gap even with relatively poor sources of lysine like wheat or corn. Keep and eye on your total, and if you hit 80 you'll probably be safe. This is the easiest way to meet lysine needs and have adequate complete protein without worrying about how much different sources have.

2. If you wish to eat a lower protein diet (or need to do so for medical reasons like kidney disease), you can supplement your diet with a few rich sources in the form of certain beans and legumes. While legumes vary in lysine content per serving and per calorie, at least two (preferably more) servings a day of soy products, peas, or an assortment of other legumes (be sure to eat a variety) can probably give you enough of a lysine boost to meet your needs even if the rest of your diet is otherwise poor (such as largely from grains and fruit).

Two servings of green peas, for example, contain 25% of your daily lysine needs, and two servings of chickpeas contains over 50%.

Some legumes, like peanuts, are rich sources per gram, but not as rich sources as other beans per calorie (roughly 1/3rd compared other beans on a calorie basis), so if you are trying to increase your lysine consumption without increasing calories that may be something to consider.

If you don't like other beans and rely mostly on peanut butter, you may need to eat an extra serving or two to get enough if you're reducing other food intake to make room for the extra calories. You can track your lysine consumption for most foods through nutrition tracking websites and apps if you have strict calorie or low protein goals.

Here's a table of lysine rich foods for convenience (but please don't rely on this alone, nutrition data can occasionally be in error):

| Lysine per | 100 calories | 100 grams |

|---|---|---|

| Boiled Lentils | 27% | 31% |

| Black Beans | 23% | 30% |

| Pinto Beans | 22% | 31% |

| Broccoli | 22% | 8% |

| Green Peas | 19% | 15% |

| Chickpeas | 18% | 29% |

| Watermelon | 10% | 3% |

| Peanut Butter | 7% | 42% |

Leafy green vegetables like broccoli are good sources of lysine per calorie (and good sources of almost everything by calorie), but they are poorer sources by weight and volume making it difficult to use them as a source (most people find it difficult to eat large volumes of vegetables). Watermelon is a rare rich source of lysine per calorie outside of legumes and vegetables, but due to high water content watermelon is very low in lysine by weight, so if using it as a source a large amount needs to be eaten daily which probably is not practical. It's included in the table as an example of a impractical but theoretically good source.

It can be complicated to restrict calories and total protein, so for most people the best advice is just to eat more protein overall and not worry about amino acids. Again, as long as you're eating ~80g of total protein you shouldn't need to worry about it. If you're suffering from kidney disease and obesity, and for medical reasons (in consultation with your doctor) you have determined that you need to restrict protein and calories, your best option would be to visit a dietitian to help you plan your diet more carefully to ensure you meet your amino acid needs on a low protein low calorie diet.

The second issue with protein has nothing to do with biological needs: Satiation.

People often complain of vegan food not being very satiating, and a major reason for this can be the lower protein concentration. Total protein is satiating regardless of the amino acid profile.

While people on standard American diets have been accused of being "proteinaholics", it does nothing for vegan outreach to promote vegan food that leaves people feeling unsatisfied. There's also no health reason to do it.

Unless you're suffering from kidney disease or have gone into ketosis due to inadequate calories from non-protein sources, it's a Myth that protein in itself is harmful.

Harm derives only from the type of protein. Longevity studies in animals have linked specific amino acids, like methionine, with shortened lifespan, and there's mechanistic evidence to believe these proteins in excess are harmful to humans as well. As it so happens, most plant proteins are significantly lower in methionine than animal proteins; only sesame seeds and brazil nuts stand out as rich sources among plant foods. If you're after optimal nutrition, it's probably a good idea to go easy on the sesame and brazil nuts, but otherwise there's no good reason to fear plant proteins as a satiating component of the diet.

Aiming for 100 grams of protein a day can not only help ensure complete nutrition given varying amounts of amino acids in plant proteins (meaning you never have to think about amino acids), but since that's comparable to levels consumed in a typical western diet it can help prevent an unsatiated feeling, and ensure that vegan food options are satisfying alternatives for the mainstream.

Legumes are among the best, easiest, and healthiest sources of protein for vegans or anybody who can eat them, they count as a protein source and due to fiber and phytonutrients are like vegetables too. Legumes are healthiest eaten cooked or fermented (as in tempeh or natto), but while some can be eaten raw (like green peas), others are toxic unless fully cooked (cooking breaks down the toxins). Many plant-based meats (Mock meats) are made from legume products and protein and some made from grain protein, some are closer to whole foods like tofu and some are more processed. Those made from legumes and legume protein are good sources of lysine. While plant-based meats tend to lack as much fiber and the phytonutrients as beans (meaning they unfortunately don't act like vegetables), they're also good sources of protein and are usually a healthy and satiating addition to the diet.

Bodybuilding

More than about 0.75 grams per lb of body weight seems to be unnecessary for most body builders, and this is easy to get on a vegan diet without any protein supplements (if desired, although protein powders can be convenient for recovery smoothies). The only thing one need be mindful of is choosing more legumes and avoiding too many starchy or fatty foods which are lower in protein; very high carb diets (like starch solution, 80/10/10) are not suitable for bodybuilding, although may be suitable for very high cardio athleticism where extra calories are being expended.

Even for vegan diets high in protein rich legumes, there is concern that the lower concentration of amino acids such as methionine and leucine may in theory make the protein slightly less effective in a competitive setting. Additionally, consuming fiber with meals can reduce absorption of protein.

There's limited research into these issues, but they don't seem to be a limiting factor for high profile vegan bodybuilders and athletes like Patrik Baboumian and Clarence Kennedy.

If you are concerned that you aren't achieving optimal performance, you can always experiment with amino acid supplementation. Supplements are typically produced by bacteria, and isolated amino acids are relatively cheap and easy to find online.

Keep in mind that supplementing with those substances which are thought to be one of the the reasons diets high in animal products are inferior in health outcomes to plant based diets may reduce or eliminate the likely health benefits of veganism with respect to longevity and chronic disease.

Choline

Adequate choline, even by the standards of DRI, is relatively easy to obtain on a vegan diet which is rich in cruciferous vegetables (like broccoli) relatively whole soy, peanuts, & sunflower products (e.g. do not rely on refined oil or protein powder), which are rich sources. Cereal grains are usually not good sources with the exception of quinoa (which is a good source, although technically a pseudocereal).

Basically no other vegan staples have significant amounts of choline. Vegans who do not eat these products may have significant trouble reaching adequate amounts and should consider a modest supplement or lecithin which is a concentrated (non-food staple) source. However, in recommending modest supplementation for some vegans that is not to say the DRI needs to be met or that large supplements should be taken. We do not like to recommend intentionally falling short of the DRI, but there are occasional circumstances where the DRI is not based on good evidence, and may even go against good advice for optimal health. Choline in large amounts may not be benign.

Choline recommendations are an issue complicated by several factors.

Potential Harm

Not only does choline feed certain kinds of growing cancer cells (not directly cause cancer, but feed it if it's already there) [55][56][57][58], but also choline is metabolized by gut microbes into trimethylene N-oxide (TMAO) [59] which promotes blood clotting and increases the risk of cardiovascular events from strokes to heart attacks.

For vegans this harm may be mitigated: studies show that vegans' gut bacteria only produces TMAO from choline in negligible amounts, unlike people eating animal products, and it's because of the lack of the gut bacteria that makes the process happen.

"The formation of TMAO from ingested L-carnitine is negligible in vegans."[60]

"Gut microbiota γBB→TMA/TMAO transformation is induced by omnivorous dietary patterns and chronic l-carnitine exposure."[61]

If consistent carnitine 'exposure' is what grows the gut bacteria that produces TMAO from choline, by not regularly ingesting carnitine (like through meat or carnitine containing drinks) you would not be growing those TMAO-producing bacteria--and at least in theory avoid the risks that come with it. So if you do supplement choline or make sure you're hitting the right amount of choline through foods, having a plant-based diet would be crucial to avoid TMAO, since regular consumption of carnitite, and possibly other omnivorous dietary patterns would only accelerate the growth of the gut bacteria that produces TMAO from choline--as explained above.

That is the theory anyway -- however, vegans should probably not assume themselves completely immune to this issue and still approach mega-doses of choline with caution (like those advocated in neurotrophics). Any readily available source of choline could create the environment to feed that kind of bacteria: if you feed it, they will come.

Beyond supplements, the generally lower levels of choline in a vegan diet vs. omnivorous diets are probably one protective aspect in adults, and there seems to be no compelling reason for vegans to go out of their ways to meet the DRI when the effects of doing so are more likely harmful than helpful in most non-pregnant adults.

However, that is not to say that a modest supplement to ensure you're getting our best guess at an optimal amount (somewhere close to the DRI) a day would not be a bad idea for vegans with a diet lower in cruciferous vegetables or limited soy/peanuts/sunflower seeds. Trying to cap it under the DRI would probably be a good idea for most people.

Unknown Requirements

We don't really know how much choline we need within a reasonable range. We know 425 mg and 550 mg for women and men respectively is adequate for pretty much everyone, and we know 50 mg is inadequate and leads to liver damage, but this leaves a huge span of unknown. The best guess is around 300mg for most people, to quote vegan dietician Jack Norris:

"The data on choline and chronic disease (cardiovascular disease, dementia, and cancer) is somewhat mixed. Ideal amounts appear to be about 300 mg per day. Most vegans probably get about that much from the foods they eat."

Most vegans probably get about that much -- if eating those common staples. However vegan diets may vary, and an allergy or intolerance can easily exclude one or more of those. There is also considerable variability in human genetics, with some people needing more or less. Children and pregnant women may also need additional choline to reduce risk of cognitive effects.

As such, in an abundance of caution, Pregnant and breastfeeding women should make sure to get the DRI, for which a modest supplement would probably be helpful (in practice it can be very difficult for pregnant women to get enough Choline, particularly as a major source -- vegetables -- is often off the menu due to pregnancy related food aversions).

Also people who suspect poor liver function should talk to their doctors and consider supplementation.

Young children and teens are at low risk of having developed cancer to feed and likely have very low risk of cardiovascular issues, and so should also get the DRI to ensure proper development since at that age higher levels of choline present little risk at those ages.

Other B vitamins

Vitamin B-1 (thiamine)

Thiamine is an essential nutrient. It's needed to turn food into energy, and it's important for the nervous system, the brain and the heart.

The RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) for thiamine is 1.2 mg and 1.1 mg, for men and for women respectively. [62]

Thiamine is widely found in plant foods, especially in whole grains, beans and legumes. Some examples include:

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast: roughly 5 mg thiamine

- 50g sunflower seeds: roughly 0.75 mg thiamine

- 1 cup lentils, cooked: roughly 0.34 mg thiamine

- 1 cup green peas, cooked: roughly 0.36 mg thiamine

- 1 cup black beans, cooked: roughly 0.4 mg thiamine

- 50g tahini: roughly 0.6 mg thiamine

- 1 cup barley, cooked: roughly 0.39 mg thiamine

Seeing how easily found thiamine is in plant foods, there's no need for worry in healthy vegan diets.

Vitamin B-2 (riboflavin)

Riboflavin is an essential nutrient. It's important for the metabolism of macronutrients and for the production of other B vitamins.

The RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) for riboflavin is 1.3 mg and 1.1 mg, for men and for women respectively. [63]

Riboflavin is widely found in plant foods in small amounts. Some of the highest sources include:

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast: roughly 5 mg of riboflavin

- 100g mushrooms: from 0.1 mg to 0.4 mg of riboflavin

- 2 cups broccoli, cooked: roughly 0.4 mg of riboflavin

- 50g almonds: roughly 0.55 mg of riboflavin

- 2 cups spinach, cooked: roughly 0.85 mg riboflavin

Considering that riboflavin is found easily in plant foods--and even if excluding the highest plant sources of riboflavin, the majority of all plant foods contain it at least in small amounts--there's no need for worry in healthy vegan diets.

Vitamin B-3 (niacin)

Niacin is an essential nutrient. It's an important key for metabolism, especially for the nervous system, the skin and the digestive track. [64]

The RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) for niacin is 16 mg and 14 mg, for men and women respectively. [65]

Niacin is easily found in plant foods, especially in whole grains and nuts. Some examples include:

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast: roughly 28 mg of niacin

- 1 cup brown rice, cooked: roughly 5 mg of niacin

- 4 tbsp peanut butter: roughly 8.5 mg of niacin

- 1 cup green peas, cooked: roughly 3.5 mg of niacin

- 2 slices (100g) whole wheat bread: roughly 4 mg of niacin

- 100g mushrooms, cooked: from 4.5 mg to 14 mg of niacin (white mushrooms: 4.5 mg; portobello: 6 mg; enoki, raw: 7 mg; shiitake : 14 mg)

Niacin's RDA is easy to reach, therefore there shouldn't be any worry in a healthy vegan diet.

Vitamin B-5 (pantothenic acid)

Pantothenic acid is an essential nutrient. It's another important key for metabolism.

The RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) for pantothenic acid is 5 mg. [66]

Pantothenic acid is found in many and different plant foods. Some examples are:

- 50g sunflower seeds: roughly 3.5 mg of B-5

- 100g mushrooms, cooked: from 1.4 mg to 3.6 mg of B-5 (enoki, raw: 1.4 mg; white mushrooms: 1.5 mg; shiitake: 3.6 mg)

- 1 cup sweet potatoes, cooked: roughly 1 mg of B-5

- 1 cup lentils, cooked: roughly 1.3 mg of B-5

- 1 cup broccoli, cooked: roughly 1 mg of B-5

Pantothenic acid's RDA is easy to reach, therefore there shouldn't be any worry in a healthy vegan diet.

Vitamin B-6 (pyridoxine)

Pyridoxine is an essential nutrient. It's another important key for metabolism, involved in over 100 enzyme reactions. [67]

The RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) for pyridoxine is 1.3 mg. [68]

Pyrodixine is found, again, in different plant foods. Some examples are:

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast: roughly 5 mg of pyridoxine

- 1 banana: roughly 0.5 mg of pyridoxine

- 1 cup sweet potatoes, cooked: roughly 0.3 mg of pyridoxine

- 1 cup spinach, cooked: roughly 0.4 mg of pyridoxine

Pyrodixine's RDA is easy to reach, therefore there shouldn't be any worry in a healthy vegan diet.

Vitamin B-7 (biotin)

Biotin is an essential nutrient. It's another important key for metabolism, especially for hair and skin. [69]

While the RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) for biotin is not known exactly [70], it's estimated to be at 30 mg. [71]

Biotin is easily found in plant foods, especially in legumes, nuts and seeds. Some examples are:

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast: roughly 10 mg of biotin

- 4 tbsp peanut butter: roughly 12 mg of biotin

- 50g sunflower seeds: roughly 6.5 mg of biotin

- 1 cup sweet potatoes, cooked: roughly 5 mg of biotin

- 100g soybeans, cooked: roughly 20 mg of biotin

Biotin's RDA is easy to reach, therefore there shouldn't be any worry in a healthy vegan diet.

Vitamin B-9 (folate)

Folate is an essential nutrient. It's extremely important for metabolism, as its deficiency can lead to a wide variety of issues, including birth defects, infertility, stroke, heart disease and multiple types of cancer. [72]

The RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) for folate is 400 mcg. [73]

Folate is extremely easily found in plant foods. Some examples are:

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast: roughly 500 mcg of folate

- 1 cup chickpeas, cooked: roughly 280 mcg of folate

- 1 cup broccoli, cooked: roughly 170 mcg of folate

- 1 orange: roughly 40 mcg of folate

- 1 cup lentils, cooked: roughly 360 mcg of folate

- 1 cup kidney beans, cooked: roughly 130 mcg of folate

- 1 cup beets, cooked: roughly 140 mcg of folate

Folate's RDA is easy to reach, therefore there shouldn't be any worry in a healthy vegan diet.

Vitamin K

Vitamin K is a group of fat-soluble vitamins. The two primary forms are called K1, also called philloquinone, and K2, also called menquinone. Both are needed for important functions.

Vitamin K1 is found plenty in green leafy vegetables (like kale, spinach, turnip greens, collards, swiss chard, mustard greens, parsley and romaine) and other vegetables such as Brussels sprouts, broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage. Vitamin K2 is found primarily is animal products, with a few exception for fermented foods such as natto, tempeh and sauerkraut.

The lack of K2 in vegan foods is a somewhat common misconception as to why a vegan diet would be deficient in vitamin K2. The reality is that the body converts what it needs for vitamin K2 from vitamin K1 [74], thanks to bacteria that lives in the digestive track. The conversion rate is relatively unknown, but some studies suggest it to be between 5% and 25% [75], but it's more commonly considered to be around 15%.

There's also a misconception that the inefficient conversion of K1 to K2 means that the body wouldn't be able to convert all the necessary K2 that it needs. This is false, as just one cup of kale would provide more than enough daily of both forms of vitamin K.

While the adequate intake of vitamin K1 is 90 mcg for women 120 mcg for men, a consensus has not been reached for vitamin K2 recommended amounts. However, studies suggest that the first preventive effects of K2 are seen at 32 mcg daily, while the ones on the high end are seen at 180 mcg daily. [76]

That said, just one cup of cooked kale contains 1130 mcg of vitamin K, which would be also sufficient for the vitamin K2 needed (after conversion).

1 cup of cooked kale = 1130 mcg of vitamin K1

1130 mcg of K1 * 0.15 (conversion rate) = 170 mcg of K2

That is from one small serving of kale, while on a healthy vegan diet you should have multiple servings of foods containing vitamin K daily.

Considering that such small quantities of leafy greens have such huge amounts of vitamkin K, it means the worry for vitamin K in healthy vegan diets is unfounded.

In fact, when using certain drugs like coumadin (which works by poisoning vitamin K metabolism), it's recommended to talk to your doctor about dosing the amount of green vegetables intake, as too many would give such a consistent dose of vitamin K that it would undermine the drug's effectiveness.

Selenium

Selenium is a an essential mineral. It's found in soil and in water, and it's absorbed in plants. [77] Selenium is incorporated into cysteine, and this process is required for certain proteins synthesis (selenoproteins), which require selenium to be fully functional. Selenoproteins are important for antioxidant enzymes, thyroid regulation, fertility, and reducing the potency of certain viruses.

The RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) for selenium is pretty vague, with the most common recommendations being 55 mcg daily [78] to 70 mcg daily.

In fact, different countries have different recommendations for selenium,

"mainly because of uncertainties over the definition of optimal selenium status" [79]

According to that study, to optimize the selenium concentration, roughly 105 mcg daily would be required--with selenium deficiency more commonly set below the values of 55 mcg to 66 mcg [80] of daily selenium intake.

However, when we consider the amount of selenium found in plant foods, the question of whether or not selenium is of any worry in a vegan diet would become trivial. Selenium is widely found in plant food:

- 1 cup of whole-wheat pasta, cooked = almost 40 mcg of selenium