Saturated Fatty Acids

Please note, this article is a work in progress.

Contents

Saturated vs Unsaturated Fatty Acids

The terms saturated and unsaturated refer to the structure of the chains of hydrocarbon of the fatty acid. If a fatty acid molecule has no double bonds it becomes saturated with hydrogen atoms and is thus referred to as a saturated fatty acid. A lack of double bonds in the "tails" of a fat causes the molecules to stack up and form a solid at room temperature, whereas unsaturated fatty acids are said to have one or more cis double bonds, which causes a kink in the chain of hydrocarbons that prevents stacking up of fatty acids at room temperature. Saturated fats are largely found in animal products, with their major sources being lard, butter, and tallow. Exceptions in plant foods include palm and coconut. Sources of unsaturated fats generally include plant and fish sources. Keep in mind, foods are a mix of different types of fatty acids, (see the graph).

Saturated Fatty Acids (SFA)

Mono Unsaturated Fatty-Acids (MUFA)

MUFAs are a type of fat where the fatty acid(s) contain one double bond.

Polyunsaturated Fatty-acids (PUFA)

More than one double bond.

Trans Fatty-Acids (TFA)

How Do We Know That SFAs Increase Risk Of CVD?

Scientific Consensus

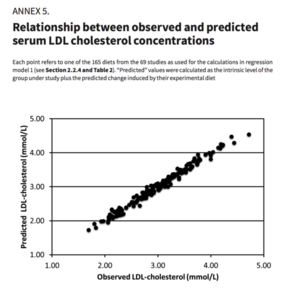

SFAs Increase LDL

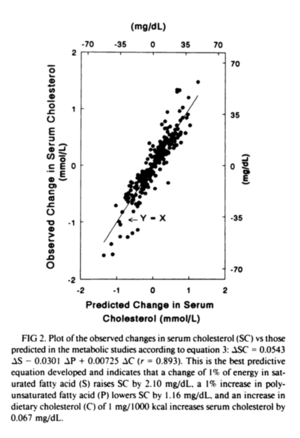

The main mechanism by which SFAs are dangerous to heart health, is their ability to raise LDL-C. Since LDL-C is causal to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)[1], this gives strong grounds to keep dietary intake low. To understand how cholesterol causes heart disease, please see the full article on Cholesterol.

Mortality/Morbidity Outcomes

There are over ten systematic reviews and meta analyses of both observational studies and RCTs encompassing millions of people that establish reducing or replacing saturated fat with other nutrients results in significantly decreased CVD morbidity and/or mortality8-20.

After considering evidence from 47 systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (2019) concluded the following:

•Saturated fat increases blood cholesterol •Saturated fat increases the risk of CVD outcomes •Replacement of saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat reduces this risk •The percentage of calories an individual consumes from Saturated Fatty Acids should not exceed 10% of calories •There is no reason to change current recommendations to reduce saturated fat intake and/or substitute with polyunsaturated fat. [30]

While there are also a few additional reviews suggesting that it has no observable effect21,22, they have flaws.

Directly contradicting both of these trials is the recent Cochrane Review on reductions in saturated fat for cardiovascular disease, which was subject to far more rigorous pre-review protocols and analyzed the results of 15 RCTs (even including SDHS) to find that long term reductions in saturated fat intake resulted in significant reductions in the incidence of combined cardiovascular events18. Furthermore, they conducted a meta regression that demonstrated larger reductions in saturated fat (and consequently greater reductions in cholesterol) elicited greater reductions in events. Unfortunately, no such regression was carried out for CVD mortality, but in the subgroup analysis stratifying by absolute saturated fat reduction a clear trend towards significant decreases in mortality can be observed, with the trial in which the greatest reduction was achieved reaching significance (Veterans Admin).

Trial 21,22 and 2-5 involve critical flaws that impair their ability to effectively assess the relationship between SFAs and CVD morbidity/mortality, and as such have been heavily criticized. Following is a discussion of each of these trials, their respective pitfalls, and additional comments from other parties where appropriate

Rejection Of Consensus

Epidemiology Denial

Correlation ≠ Causation

Common Arguments & Concepts Used By SFA Apologists

SFAs Are Most "Stable"

Chain Length

Stearic Acid

Ancel Keyes

Appeal to contradictory research

Common Studies Cited By SFA Apologists

JACC Review

A review entitled Saturated Fats and Health:A Reassessment and Proposal for Food-Based Recommendations was published in The Journal of the American College of Cardiology, in which authors presented the argument that current evidence does not support the dietary guidelines recommendations to limit saturated fatty acid (SFA) intake to less than 10% of daily calories on the basis of reducing morbidity and mortality from common chronic diseases, most notably cardiovascular disease (CVD). They remark that although SFAs raise low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), this is due to increases in large (and not smaller, dense) particles, which aren’t as strongly related to CVD risk. Further, they exclaim that not all sources of fatty acids impart similar effects on health due to differences in their overall structure and the complex matrices of the foods they are found in, specifically emphasizing that dark chocolate, unprocessed meat, and whole-fat dairy are not associated with the risk of CVD and recommendations to limit their intake solely due to their SFA content are unsubstantiated1. Although some of the sentiments they offer are agreeable, and despite their claims otherwise, the totality of the available evidence does not support many of their arguments. Accordingly, their publication will likely cause greater confusion to the american population already struggling to decide who they can trust among the disordered field of nutritional science, and result in more harm than benefit.

The review begins by briefly discussing the history behind the initiation of dietary goals and recommendations to lower saturated fat intake dating back to the 1970s, and details that since the 80s there have been specific goals of reducing saturated fat intake to less than 10% if total calories to reduce CVD risk. The authors declare that their main intention is to answer the question posed by the United States Department of Agriculture and Health and Human Services’ in 2018; “What is the relationship between saturated fat consumption (types and amounts) and the risk of CVD in adults?” by reviewing the effects of saturated fats on health outcomes, risk factions, and mechanisms underlying CVD and metabolic outcomes. Having clearly defined their objective, the question then becomes whether their review provides a sufficient answer that is backed by a solid body of evidence, which will become quickly apparent is far from the case.

In the following paragraph, they say the following:

“The relationship between dietary SFAs and heart disease has been studied in about 400,000 people and summarized in a number of systematic reviews of observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Some meta-analyses find no evidence that reduction in saturated fat consumption may reduce CVD incidence or mortality (3–6), whereas others report a significant—albeit mild—beneficial effect (7,8).2-7”

Based upon this collection of research they conclude that the basis for recommending a low saturated fat diet is unclear and that they intend to propose an evidence-based recommendation for intake of SFA food sources. Right from the start the authors have demonstrated that they aren’t truly reaching their conclusions by considering the totality of the evidence. Despite only mentioning 5 publications that contain about 400,000 subjects, there are actually over ten systematic reviews and meta analyses of both observational studies and RCTs encompassing millions of people that establish reducing or replacing saturated fat with other nutrients results in significantly decreased CVD morbidity and/or mortality8-20. In fact, a couple of the more recent publications on the subject include over double the amount of people they imply this relationship has been studied in17,19. While there are also a few additional reviews suggesting that it has no observable effect21,22, along with those that the authors of the JACC review mention2-5, they involve critical flaws that impair their ability to effectively assess the relationship between SFAs and CVD morbidity/mortality, and as such have been heavily criticized.

Taking into account the incredibly large body of high quality evidence from RCTs and observational trials demonstrating the beneficial effect of reducing saturated fat intake on CVD morbidity and mortality, and considering the problematic aspects of reviews suggesting a null effect, it should be incredibly clear the JACC author’s statement that there is a lack of clarity regarding the basis for reducing saturated fat intake is preposterous.

For a full article on this review, please see the full article on JACC Saturated Fat Review

Harcombe et al, de Souza et al, Siri-Tarino et al, and Zhu et al.

Overadjustment

Since all four fall victim to the same issue (among a few others), it will be best to first address the problems with the reviews on prospective cohort studies and case-controls assessing the relationship between saturated fat intake and CVD by Harcombe et al., de Souza et al., Siri-Tarino et al., and Zhu et al. The major methodological problem with these four reviews is the inclusion of an appreciable amount of cohorts which adjusted for serum cholesterol or baseline hypercholesterolemia (5/10, 1/3, and 5/11 cohorts in de Souza for total CHD incidence, CVD mortality, and CHD mortality, 7/16 and 4/8 in Siri-Tarino for CHD and stroke events, 3/6 in Harcombe et al., and 14/40 and 7/22 in Zhu et al. for CHD in the highest vs. lowest comparison and dose response analysis, respectively). This is particularly concerning because the action of adjusting for a moderator variable (in this case serum cholesterol, or more specifically LDL-c, which is increased in response to saturated fat consumption and increases the risk of CVD) that lies on the causal chain of the outcome of interest pulls the results of the analyses towards null, creating a biased and inaccurate observation of the true relationship. Given that almost half of the cohorts in each of these reviews make such adjustments, any effect would be especially muted. Scarborough et al. actually discuss this very issue in their comment responding to the authors of Siri-Tarino et al. closely following its publication23. While there are additional issues that may also contribute to the lack of effect (little to no variance in saturated fat intake among cohort’s sample population, inclusion of multiple cohorts with intakes all above or below the threshold where the majority of the increase in CVD risk is observed, failure to disclose review protocols, and inclusion of only CVD mortality metrics), just this alone is enough to invalidate the results of these reviews. Lastly, despite these over-adjustments, trans fat was still associated with significant increases with CHD mortality and CVD in Zhu et al. and de Souza et al., which will prove to be an important consideration with respect to some of the other reviews.

Ramsden et al

Apart from the 4 reviews just discussed, two additional reviews have suggested there may not be an association between saturated fat intake and CVD, one of which the authors of the JACC mentioned in their brief comments on the subject. These two reviews were carried out by Ramsden et al. and Steven Hamley, both including randomized controlled trials focused on determining the potential benefit of replacing saturated fatty acids with mostly polyunsaturated fatty acids. Ramsden et al.’s review included discussion of recovered data from the Minnesota Coronary Experiment (MCE) and also carried out a meta-analysis of an additional 4 RCTs, the Sydney Diet Heart Study (SDHS), the Rose Corn Oil Trial (RCOT), the Los Angeles Veterans Trial (LA Vet), and the Medical Research Council Soy Oil Trial (MRC-Soy), and a sensitivity analysis on the previous 5 in addition to 3 more, the Diet and Re-Infarction Trial (DART), the Oslo Diet Heart Study (ODHS), and the St. Thomas Atherosclerosis Regression Study (STARS).

Steven Hamley n-6 PUFA Review

In Hamley’s review of RCTs, he chose to exclude certain trials on the basis of “inadequate control” and other factors that he posits would impact the results, including suspicions that the control group had higher trans fat intake, were exposed to cardiotoxic medications, and had lower vitamin E intake. His meta analysis ended up incorporating the exact same trials as Ramsden et al.’s with the one exception being LA VET, which he replaced with DART. Ironically, this means he included both MCE and SDHS, which exposed the intervention groups to higher trans fat intake, and other small studies underpowered to detect meaningful effects on his chosen endpoints total and major CVD events.

Directly contradicting both of these trials is the recent Cochrane Review on reductions in saturated fat for cardiovascular disease, which was subject to far more rigorous pre-review protocols and analyzed the results of 15 RCTs (even including SDHS) to find that long term reductions in saturated fat intake resulted in significant reductions in the incidence of combined cardiovascular events18.

Minnesota Coronary

Not only was the MCE flawed in numerous ways that prevented meaningful conclusions being drawn from its results, there were also multiple issues with the other smaller trials included in their analysis (for which MCE ended up being weighed the most). As for the MCE, the high dropout rate (>75%) and subsequently insufficient power to detect effects on mortality, the utilization of a likely trans fat-containing margarine in the intervention group, the fact that the main difference in mortality was observed only in subjects over 65 years of age, and the lack of important metrics such as smoking status, LDL cholesterol, detailed dietary intake data, weight loss, and coronary disease status, were the main problems. The smaller size (and weaker statistical power), exclusion of mortality as a main endpoint, and inclusion of a trans fat based margarine in the experimental group of another trial (SDHS), were further issues that rendered the findings of the analyses unuseful.

Chowdhury et al

PURE

Nutrireqs

Harcombe Review

Sydney Diet Heart

Women's Health Initiative

The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) is often cited as a large randomized controlled trial in support of the claim that saturated fatty acids do not increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. It is important to note that the goal of this study was to determine the impact of reducing total fat intake to 20% of calories by increasing intake of vegetables, fruits, and grains. The researchers presumed this would lead to a reduction in saturated fat intake to 7% of calories, but saturated fat reduction specifically, was not the goal of the trial. Evaluation of nutrient intakes did see a reduction in total fat from 37.8% to 28.8% of calories, but saturated fat only decreased from 12.7% to 9.5% of total calories and polyunsaturated fats dropped 7.8% to 6.1%. This left the P/S ratio virtually unchanged, resulting in a very minimal 3.55mg/dl drop in LDL-cholesterol levels. This explains the lack of risk reduction in the intervention group. Furthermore, the intervention group saw a rise in refined grain products and a reduction in nut consumption as well, which can further contribute to raising CHD risk. Evidently, we do not see cardiovascular benefits in the intervention group because the participants did not adhere to the level that was projected by the researchers at the outset. Interestingly, upon further analysis, those who were the most adherent and reduced saturated fat to below 6.1% of calories, had a 19% reduction in CHD risk that was driven by a 10.1mg/dl reduction in LDL-C levels. Not only does the WHI not debunk the lipid hypothesis, but it directly supports it.

References

References: https://www.onlinejacc.org/content/76/7/844 de Souza R.J., Mente A., Maroleanu A., et al. (2015) Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ 351:h3978. Harcombe Z., Baker J.S., Davies B. (2017) Evidence from prospective cohort studies does not support current dietary fat guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 51:1743–1749. Ramsden C.E., Zamora D., Majchrzak-Hong S., et al. (2016) Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968–73). BMJ 353:i1246. Siri-Tarino P.W., Sun Q., Hu F.B., Krauss R.M. (2010) Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 91:535–546. Hooper L., Martin N., Abdelhamid A., Davey Smith G. (2015) Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD011737. Mozaffarian D., Micha R., Wallace S. (2010) Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med 7. E1000252. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19211817 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC30550/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21118617 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4334131/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20351774/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4095759/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27224282 https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0939475317302375 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261561420301461 https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub2/full https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32723506/ https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/L14-5009-9 https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12937-017-0254-5#Tab4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6451787/ https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/92/2/458/4597393

Written by: Matthew Nagra BSc, ND (5.11). Matt Madore BSc (5-5.5), Riley MacIntyre (2-2.3) Aug 16, 2020