Antinatalism

Anti-Natalism is the general or universal belief that there is negative value to procreation.

While there are usually specific cases where sensible people are anti-natalist in a limited sense, like during wars, that in itself is not anti-natalist in the broad sense (which this article discusses). Likewise, vegans usually hold or even promote limited anti-natalist positions with respect to farmed animals and believe breeding these animals for a life of suffering and an early death is wrong, again that is in itself not anti-natalism.

Anti-natalists do not have objections merely to specific cases of procreation where inordinate harm is involved, but to procreation generally even from healthy, secure, well adjusted parents; and even to socially and environmentally conscious parents who would pass those values onto their children.

The claim, as many broad claims are, is typically deontological (or dogmatic) in nature and not founded on consequentialist reasoning that considers exceptions. There are consequentialist anti-natalists, but usually of a special negative-utilitarian variety.

Contents

Being vs Promoting

Before addressing the philosophical and empirical matters that may suggest antinatalism is correct or incorrect as a position, it's important to make the distinction between being an antinatalist or personally believing and following antinatalism versus advocating or promoting the position to others as part of activism.

Somebody may be an antinatalist in the philosophical sense that he or she believes procreation is always (or virtually always today) wrong, and perhaps lives accordingly, but that doesn't necessarily mean it's a good idea to promote that position today. There are a number of pragmatic and consequentialist reasons why an antinatalist may chose to remain silent about the position, or even understand it to be wrong to promote in the modern context due to its consequences. These reasons go beyond the personal and professional consequences of promoting an unpopular or offensive ideology (like ruining relationships) to compelling moral reasons why a believer in antinatalism might want to leave these ideas on the back burner -- if not because they're inherently problematic in terms of their consequences, then in the least because the world is "not ready" for them yet.

Inefficacy

As a long-shot cause, antinatalism is far out there (beyond veganism and other already difficult to promote causes). The desire to have children is very strong, and may even be instinctual and impossible or impractical to substitute -- this is in contrast to veganism, particularly in the sense that there's not necessarily any desire to eat meat that can't be replaced by alternatives. Antinatalism is an inherently more difficult ask for people who don't already prefer being childless (for whom the argument is not necessary).

There's also bad historical precedent for ideologies like antinatalism. While rights movements (like anti-slavery, women's rights, anti-racism) have had a gradual and multi-generation march to progress, ideologies and religions that forbade reproduction do not have very long lives or ability to spread; they have a very poor ability to expand on the progress of the prior generation or pass on values. While values can move laterally between acquaintances or even strangers through speech, the dominant vector for ideologies is still through lineage (with very gradual change).

While being a long shot isn't necessarily a good reason not to promote a cause on its own, it is a good reason in the presence of other competing causes that have better odds of doing good (and less chance of doing harm). Promoting one cause typically comes with the opportunity cost of not promoting another or promoting it less effectively, thus why promoting antinatalism may take a necessary backseat as a case of moral priority to promoting more effective causes that more people agree with like ending wars, green energy, and reducing human reliance on animal products. This is, incidentally, why some vegans choose to practice veganism but only promote reducetarianism.

Association

While some activists attempt to take an intersectional approach to promoting things like veganism and antinatalism side by side, the less palatable point to any given audience may cause harm to the more acceptable one -- in short, as a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, so is a bundle of ideas (particularly restrictions) only as appealing as its most objectionable part.

Pairing veganism with antinatalism inevitably makes it harder to spread the vegan message to those who do not already agree with antinatalism, and for those who do agree (an incredibly small minority) the "preaching to the choir" aspect is unnecessary.

Guilt by association is typically a fallacy, and yet it's a matter of fact that many people naturally think that way. Activists need to act in ways that are compatible with how people DO think and not with how they believe people SHOULD think in an ideal world we don't live in. When vegans promote other radical positions that can put people off, and particularly when they present them as part of veganism, they risk alienating people from veganism in the process. Thus a person who may have gone vegan may be put against it by the bigger ask of never having children if he or she wants to join the movement.

This harm only increases as the antinatalist position becomes stronger and even endorses the use of force.

Dysgenics

It's an inevitability today that not everybody is going to come on board with antinatalism willingly. IF the proponent is against forced sterilization, forced abortions, imprisoning people for disagreeing with the ideology, etc. (things that most sensible people are against) then regardless of the size of the antinatalist campaign there will still be people reproducing. The selective pressures with anything that acts directly on reproduction like this are substantial. If there is any inherited component to the desire to have children, and/or even any inherited component to the tendency to accept and follow antinatalism philosophically (like higher compassion, intelligence, impulse control, etc) then any broad campaign for elective antinatalism in a population would have a dysgenic pressure against those positive traits that are associated with antinatalism (if they indeed are) and in favor of the presumably negative trait of desiring children.

"Dysgenic" here is used broadly to include all heritable traits, both genetic and otherwise; whether nature in terms of genetics, epigenetics, or nurture in terms of early childhood environment or other unknown factors. In any case with some form of heritability the result is the same: the kinds of people who follow antinatalism are selected against, and the traits tied to that go with it which could plausibly be a less compassionate, less intelligent, more impulsive population that has a much stronger innate desire to have many children -- enough so that the anti-natalist movement ultimately creates the conditions for its own demise, and we're even worse off than we were before by their own metrics.

None of this is to suggest support for eugenics, only outline a likely unintended consequence. Any pressure for antinatalism, when applied selectively, acts as any Darwinian pressure does. The only option that avoids this selective pressure is one that involves a substantial measure of force (e.g. forced abortions, sterilization, imprisonment, etc.) applied broadly and involuntarily across the population, which isn't something most vegans would accept and certainly not something most people would accept. If you start promoting force with antinatalism then the efficacy of that advocacy drops dramatically while the negative associations grow and harm anything the ideology touches. That doesn't stop a fringe from supporting that view (see Efilism), but it's something to consider if you don't advocate extremism.

So even if it is wrong in some philosophical sense to have children, it's very plausible that the net effect of promoting that view may also have harmful consequences which outweigh any nominal benefit, or result in an effect counter-productive to the goal. It's possible to not have a goal if the antinatalist position derives from a deontological rule that having children in and of itself regardless of consequence is wrong, but the dysgenic effect should be an unintended consequence that anybody of a remotely consequentialist mindset should be wary of when considering promotion of antinatalism. Antinatalism is fairly unique among ideologies in this counter-productive effect.

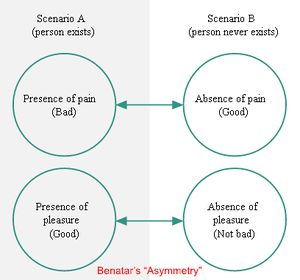

Benatar's Asymmetry

Benatar's Asymmetry is likely the most popular argument among self-styled antinatalists, but to be clear it's also probably the worst argument there is for antinatalism (incidentally, it's also one of the Bad Arguments for Veganism). Even antinatalist-leaning philosophers do not hesitate to recognize the serious problems in Benatar's asymmetry, and for anybody interested in going deep down the rabbit hole of fractal wrongness that is the argument, those and other published criticisms are well worth checking out:

- Julio Cabrera: Quality of Human Life and Non-existence[1]

We cover Benatar's Asymmetry as an overview in this article due to its popularity, and doing so as the first argument is both because of its popularity and to get it out of the way so we can address more potentially credible arguments (such as the empirical environmental arguments for a smaller population). To be very clear, we don't mean to represent Benatar's Asymmetry as the gold-standard in antinatalist argumentation; to the contrary, every other argument addressed on this page is more worthy of exploration and careful consideration.

An eloquent summary of the relative merits of antinatalist argumentation:

Antinatalism (applied to modern humans) is a neat illustration of how the reasoning someone follows to arrive at a conclusion can tell you more about the person than the conclusion itself tells you.

If you're an antinatalist because you think people experience more suffering than pleasure, then I disagree, but I think it's an empirical question, and I can imagine your position being correct.

If you're an antinatalist because you're a negative utilitarian, then I think the axioms of your moral system are deeply unappealing, but at least not fundamentally inconsistent.

If you're an antinatalist because of Benatar's asymmetry, then I think you've fallen for one of the most flagrantly ridiculous arguments in modern moral philosophy. -Evan Sandhoefner (img)

Qualitative Benatar's Asymmetry

Benatar's asymmetry claims on intuition that the absence of pain is good, but the absence of pleasure is not bad.This is related to negative utilitarianism, which bases assessment only on pain and ignores pleasure entirely. The apparent distinction is that Benatar doesn't deny the positive value of pleasure during existence as negative utilitarians do (which makes it more intuitively palatable), but this may be a meaningless distinction if you only look at qualitative (all or nothing style) comparison as in canonical diagrams (and as he seems to prefer):

My view is not merely that the odds favour a negative outcome, but that a negative outcome is guaranteed. The analogy I use is a procreational Russian Roulette in which all the chambers of the gun contain a live bullet. The basis for this claim is an important asymmetry between benefits and harms. The absence of harms is good even if there is nobody to enjoy that absence. However, the absence of a benefit is only bad if there is somebody who is deprived of that benefit. The upshot of this is that coming into existence has no advantages over never coming into existence, whereas never coming into existence has advantages over coming into existence. Thus so long as a life contains some harm, coming into existence is a net harm. -David Benatar[2]

That is, the absence of life is always qualitatively "good" to Benatar, but the presence of life may be "good" or "bad" (depending on how lucky you were based on how much pleasure or pain there is). The certainty of good, Benatar believes, always outweighs the chance of it. The way he achieves this dichotomous result is through all or nothing style analysis (good life or bad life) with no concept of gradation or weighing the magnitude of good or harm in different scenarios against each other.

There are essentially two methods by which the results can be interpreted to arrive at the absolute conclusion Benatar wants.

- Never quantify good and bad to begin with (see explanation here)

- Quantify it to get a scalar value of goodness or badness for the life (something on a spectrum), then sanitize the results afterwards to a good/bad boolean style value (either negative or positive, nothing in between) for simple qualitative comparison

Benatar does the latter in order to preserve the appearance of recognizing that some lives are or could be good for intuitive appeal. It is proposed to work as such:

Consider Bob, who has a wonderful life filled with happiness (10 happiness), but he gets a paper cut once (1 pain).

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 10 Pleasure | 10 | 0 |

| Pain | -1 | 1 |

| Total | Good | Good |

Because the good was larger than the bad, the life is considered a "good" life. But because good is also larger than bad for non-existence, that's also considered "good". Because the quantities have been scrubbed away (discarding the information that the life is more good than the non-existence is bad) in favor of dichotomous qualitative statements, Benatar's claims of certainty would follow only from saying they're both good, so it's a wash.

However, because not all lives will be good, there is a risk of existence being worse than non-existence.

Consider Tom, who has a terrible life filled with misery (10 pain), but he gets a tasty cookie once (1 happiness).

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Pleasure | 1 | 0 |

| 10 Pain | -10 | 10 |

| Total | Bad | Good |

Here the magnitudes are again scrubbed away, but one is bad and the other is good. Life in this case would be inferior to non-existence.

So, Benatar argues, because the best case is a good life and in those cases non-existence is also good, but in the worst cases there's a bad life where non-existence would be good, betting on non-existence being superior on average is not just a good bet but a sure thing.

Because you fail to consider the magnitude of good and bad, and only look at a dichotomous result, some lives must inevitably be assessed as bad and non-existence is always good. Thus Benatar's Asymmetry (if it works as he claims) makes superfluous the otherwise crucial empirical arguments about the balance of pleasure and pain in life.

Quantitative Benatar's Asymmetry

A serious problem is that despite Benatar recognizing the fact that these things can be quantified and weighed (he recognizes a life can be net bad even if there's some good in it), he is unwilling to engage in quantitative analysis of the goods and bads in life vs. unlife. This makes his claims inherently inconsistent, and probably also intellectually dishonest if he uses arguments that are inconsistent with his own when it suits him.

If we examine quantity of good or bad, the effect is that the asymmetry argument engages in double counting for pain without justification, but that it isn't impossible for life to be better than non-life. That is, it does not make the empirical arguments unnecessary as Benatar claims.

As an example, consider the existence or non-existence of Bob, who has a life with 5 units each of pleasure and pain (presuming we have a good method to measure it):

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 units Pleasure | 5 | 0 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 5 |

| Total | 0 (neutral life) | 5 (good non-existence) |

Here Benatar's asymmetry (no matter how it's assessed) would says that it's better than Bob not exist than exist.

Even with a comparatively good life, this is the case:

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 6 units Pleasure | 6 | 0 |

| 4 units of Pain | -4 | 4 |

| Total | 2 (Good life) | 4 (Better non-existence) |

Benatar's asymmetry would even claim that people with good lives, including significantly more pleasure than pain, would be better off not existing, which is a very serious violation of intuition, but at least follows from his premises.

Where the claim meets a contradiction is that this is not always the case in a comparative assessment. In order to even break even in quantitative analysis, a life would have to contain twice as much pleasure as pain. However, contrary to Benatar's claims, if a life is sufficiently happy, it obviously IS better than non-life even if we blindly accept unjustified double counting of pain; that is if the two scenarios are assessed honestly with a quantitative comparison rather than ad-hoc sanitization of the results.

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 10 units Pleasure | 10 | 0 |

| 2 units of Pain | -2 | 2 |

| Total | 8 (Very Good life) | 2 (Slightly good non-existence) |

Here existence is clearly preferred (offering more good) than non-existence. So if Bob lives a great life of happiness and contentment and gets a paper-cut once, it IS better that he had lived than not. This should be intuitively obvious, but even if it isn't intuitively obvious it's the only honest conclusion following from a consistent application of measurement standards. Benatar is simply wrong that it is guaranteed that life will always be less than non-life, the result is leaving the question of whether we should or should not have children up to empirical contention. It is plausible (or at least an open question) that a significant number of humans and non-human animals live lives they would consider at least twice as happy and pleasurable as they are sad, and so if used consistently, an honest interpretation of Benatar's asymmetry does not result in broad antinatalism.

The only way Benatar's asymmetry comes to the certain conclusions he wants (that life is always a bad gambit vs. non-life) is to engage in not one, but two forms of unjustified manipulation: Double counting pain AND assessing the results only qualitatively (good or bad) rather than quantitatively (a spectrum).

Alternative Qualitative Asymmetry

Never-Quantified assessment is one viable alternative to Benatar's approach may be suggested to preserve the asymmetry without the appearance of intellectual dishonesty.

This is the alternative method of assessment mentioned in the first section (Never quantify good and bad to begin with) and what makes it at least potentially more intellectually honest because it could be paired with the belief that pleasure and pain are inherently unquantifiable and incomparable.

Like negative utilitarianism, though, this approach is a serious violation of intuition and it would cost the most appealing aspect of Benatar's argument vs. true negative utilitarianism (Benatar's recognition that some lives could be good).

As an example:

Consider Bob, who has a wonderful life filled with happiness and pleasure, but he gets a paper cut once. The happy life merely counts as "pleasure" which is good, and the paper cut counts as "pain" which is bad.

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| Pleasure | Good | Neutral |

| Pain | Bad | Good |

| Total | Neutral (good+bad) | Good |

Because there is no quantification at all during life, all lives inevitably result in a neutral output, or "good + bad".

Consider Tom, who has a terrible life filled with misery and pain, but he gets a tasty cookie once. The life of misery merely counts as "pain" which is bad, and the cookie counts as "pleasure" which is good.

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| Pleasure | Good | Neutral |

| Pain | Bad | Good |

| Total | Neutral (good+bad) | Good |

Again, the exact same result.

Here a life of happiness with one paper cut looks the same as a life of misery with one tasty cookie as an exception. All lives have good and bad, but all non-existence just has good, so the latter always wins in a comparison (but may not be compelling, more on that shortly).

Such an asymmetry paired with a belief in the inherent quantitative incomparability of pleasure and pain could result in an apparently consistent outcome. Of course, it's one that claims a life of suffering isn't any worse than a life of bliss because they both contain pleasure and pain: such a claim is a profound violation of intuition unlikely to be taken seriously by anybody at all, and it's not the canonical Benatar claim (so it's beyond the point here).

The consequences of such beliefs would also be very troubling: to not bother preventing (and not worry about causing) additional suffering for living beings because it makes no difference. A further consequence to antinatalism limits the compelling force of those antinatalist claims themselves: antinatalists could no longer claim that having children is bad, only that it's neutral, and if they wanted to attempt to claim is was bad on the basis that the lack of good was bad then the argument would defeat its own premises (unlife would also become neutral, arguing only for nihilism and not antinatalism).

The best an antinatalist could do is assert that people are compelled to always do good instead of neutral things (which would be a very strong claim), but even were this asserted, the problems of Assertions(next section) would still be relevant. And the claim of quantitative incomparability of pleasure and pain has empirical challenges.

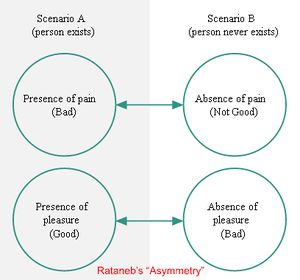

Asymmetry as an Assertion

There are many practical problems with the asymmetry argument, but the most substantial is the fact that these argument are based merely on assertions without sound justification, and they are assertions of the kind which the opposite can be just as credibly claimed with significant implications (negation and reversal of all conclusions).

In this case, the opposite assertion is the Rataneb's Asymmetry: the absence of pleasure is bad but the absence of pain is not good. (See image, right) Any half-decent debater can twist words and appeal to emotion to fabricate any number of spurious intuition-jerking arguments ad hoc to support this absurd asymmetry, for example:

When we experience a pleasurable event, that's good. But when we miss out on pleasure, like in the case of a father who dies before seeing his daughter's wedding, we understand that is bad even thought he wasn't there. It's a missed opportunity for happiness.

Similarly when we experience pain, that's bad. The asymmetry arises with missed pain, because missing out on pain is not good, it's just neutral. If you're not alive and not in pain that doesn't feel like anything at all.

It may sound convincing when it's phrased cleverly, and if you don't think about it (which is likely if you want to believe in this argument) but the argument is vacuous.

The consequences of accepting this inversion (the Rataneb's Asymmetry) would suggest that even a life of substantial net suffering (as in modern animal agriculture) to possibly be better than no life at all if as outlined in previous sections it effectively double-counts pleasure. In the case of dismissing quantitative analysis entirely (using the same all or nothing extreme Benatar favors), then even the worst factory farming would always be guaranteed to be morally good for giving life if the animal inevitably experienced some kind of small pleasure at some point in life (e.g. a hatching chick enjoyed the first steps, then everything else was suffering).

Because Benatar's asymmetry is based on no reason whatsoever (it hinges only on the audience's willingness to believe it and the presenter's persuasive eloquence), there's no reasonable argument a proponent can make against somebody claiming the precise opposite to promote any abhorrent conclusion. Such a Rataneb's Asymmetry argument could be used to promote the most cruel factory farms, or even promote procreation (and denial of birth control) in cases of impoverished, wartorn or disease-stricken areas which might actually result in substantial human suffering.

When you throw out the idea that the amount of pleasure and pain matters, you can promote any kind of position based on ad hoc assertions of asymmetry, and these assertions can be just as easily turned on their heads to advocate the precise opposite view.

The practical consequence of embracing such an arbitrary ad hoc assertion as Benatar's asymmetry is that, when faced with the counter-assertion (Rataneb's Asymmetry), an interlocutor is either forced to argue as a hypocrite with a dishonest double-standard (as Benatar himself apparently does), or to abandon the most powerful argument against the opposite assertion and fall back like a child in a school-yard argument on the counter-assertion of "no, you're wrong and I'm right because I said so. Infinity".

An opponent of the asymmetry, however, can criticize the grounds for the assertion itself, and argue that similar treatment should be given to pleasure and pain, and that quantitative assessment is crucial to understanding comparative value (otherwise we are faced with an impenetrable nihilistic sameness that negates the purpose of moral discourse).

Symmetric Alternatives

There are symmetric alternatives which consider pleasure good and pain bad, and the absence of pleasure and pain to both be neutral or both have the inverse value relative to the would-be experienced states in life. These come to identical conclusions with respect to which scenario are better, and differ only in degree of difference.

Compare neutral:

| Absence=0 | Existence | Non-Existence |

|---|---|---|

| 5 units Pleasure | 5 | 0 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 0 |

| Total | 0 (neutral life) | 0 (neutral non-existence) |

| Absence=-x | Existence | Non-Existence |

|---|---|---|

| 5 units Pleasure | 5 | -5 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 5 |

| Total | 0 (neutral life) | 0 (neutral non-existence) |

A good life:

| Absence=0 | Existence | Non-Existence |

|---|---|---|

| 10 units Pleasure | 10 | 0 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 0 |

| Total | 5 (good life) | 0 (neutral non-existence) |

| Absence=-x | Existence | Non-Existence |

|---|---|---|

| 10 units Pleasure | 10 | -10 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 5 |

| Total | 5 (good life) | -5 (a bad non-existence) |

Note that the difference between the latter set is larger, at 10 net points difference rather than 5. However, the overall prescription (to choose life instead of non-life) remains the same. Similar results are true for bad lives, where the bad life is more bad.

Here there is double counting, but because the double counting exists for pleasure and pain the outcome is not meaningfully different, and it doesn't create an unjustified asymmetry.

Therefore, there is no significant drawback to using either of these approaches, and you can freely engage in discourse with your interlocutor's preference (be that neutrality of non-existence or inverse relative value). Once established as symmetric, the only issue is scale.

Existence Bias

In the context of anti-natalist argument the claim of "existence bias" is an unfalsifiable but seemingly empirical claim that we are biased about our own existence being good or happy, so we're perpetually in error when we assess that we enjoy life/that we are generally happy about having been born, and instead are in fact subject to far more bad than good in life.

Optimism Bias vs Pessimism Bias

The first issue is that this isn't necessarily an "existence bias" which is something that sounds like it would be objective and irrefutable because obviously we exist -- rather what is being alleged is an "optimism bias". Fundamentally, this is the same kind of semantic shenanigans as we find with Benatar's asymmetry; once the real spectrum of possible biases have been considered, we can see that both optimism AND pessimism biases may be at play and there's no reason to assume that the average person is any more under the sway of an optimism bias than the average anti-natalist is under the sway of a pessimism bias; both are just assertions without evidence that are not conducive to conversation or a honest assessment of the issue.

An anti-natalist arguing on the basis of "existence bias" (optimism bias) may claim it has to do with evolution, but such a claim is a perversion of evolutionary theory. Animals evolve to actually be more suited to their environments, not merely to survive under delusions that they are more suited to their environments. If evolution has made animals more content or happy with their circumstances for purposes of survival then this is not an existence bias (or optimism bias), it's a valid modification of the baseline. Events like hunger, cold, or injuries don't have objective metrics of negative value, but rather it is the experience of those conditions that are evaluated and given value by those who experience them. If there is a bias in any direction it is not provided any credible evidence by evolutionary psychology.

Unfalsifiable Prescriptions

It's a serious problem to make controversial and forceful prescriptions for others based on unsubstantiated (and particularly unfalsifiable) claims about empirical reality. To demonstrate why this is, the very opposite can be just as easily asserted, or even apparently absurd (but still unfalsifiable) claims about factory farmed animals experiencing more pleasure than pain despite appearances: a carnist may just as well claim that the farmed animals are just stressed because they have "pessimism biases" but in fact are experiencing far more goods than bads and so the industry is moral. Assertions like this are not productive to discourse. However, the principle of why this kind of unfalsifiable claim is categorically problematic is difficult to explain to anti-natalists.

Sometimes it's helpful to understand it by analogy to other problematic cases of counterproductive political discourse today, eg. on the abortion topic.

Reliance on Hedonism

Fortunately the force of this claim, if true, also depends on on a hedonistic value system (as opposed to a preference system) where pleasures and pains can be objectively weighed against each other to come to a conclusion as to whether your life has net negative or positive value to you regardless of how you actually feel about it or what your interests are. This hedonistic claim is one that can be attacked very persuasively for most people using simple thought experiments that challenge intuitions on this point:

The "pleasure pill" challenge that puts a person in a mindless euphoric coma to maximize hedonic pleasure

It can also be challenged philosophically on its arbitrarity in light of claims of objectivity: Why is this particular electrochemical signal bad? Why is another good? What about species with different neural architecture? And finally, the claim can be challenged empirically based on its connections to psychological egoism. Challenges to hedonism can be found in more detail in Hedonism vs Preference.

Within a preference framework, such claims of Existence Bias or Optimism Bias don't make any sense unless you're talking to somebody who claims to only prefer maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain (in which case you can talk about idealized interests which may not be that), but this in itself is a very rare case and doesn't support this argument for antinatalism since its overwhelmed by people satisfying sincere non-hedonistic preferences to live for their family and other purposes even if somehow pain could somehow be found to be higher than pleasure in a technical sense.

Consent to Exist

This refers to the usually deontological claim that acting on another (i.e. inevitable harm of some measure) without consent is always wrong, and that because (according to them) a non-existent being can not consent to come into existence then the act of creating a sentient being is always wrong.

The consequentialist equivalent may accept certain justifications for acting upon others without consent, such as for some greater good (or avoiding a greater harm), though this is a slightly weaker and inevitably non-absolute form of antinatalism so it's not the primary focus of this section -- although the points still apply to the principle assumptions regarding the moral relevance of consent.

Definition of Consent

First, it can be important to understand what consent is:

consent nounDefinition of consent (Entry 2 of 2)

1: compliance in or approval of what is done or proposed by another : ACQUIESCENCE[3]

This of course tells us very little. Can I approve (consent) to another person having a child? If so, then there was consent for the child being born. This would of course be a more archaic use which can consider people as property and having rights over one another in a hierarchy of dominion that stretches up to god, but isn't ultimately contraindicated by common definitions. Likewise, can I consent to something after the fact or when the action is ongoing? These definitions don't help us out much there either; they do not say approval of what *has been* done by another, but they also don't say *will be* done; the present tense can be an ongoing action. As a child of my parents can I consent to my parent's ongoing behavior of procreation? Seemingly so, and as part of that I would consent to having being born. It's both a fuzzy definition and a fuzzy concept which is one of many problems for an absolute dogma around consent (which is not to say that consent isn't important in some situations as explained later).

In practice today, consent has a range of usages both common and more technical -- of these it is typically grouped into "types" of consent from explicit/expressed informed consent of various kinds to implied consent and consenting by proxy for somebody else and every combination thereof. Every field has its own standards for consent and its own ways of categorizing them: there is no objective qualification or accounting of the "types" of consent that would make credible any claims of "there are three/four/five types of consent in the universe" because consent exists on a spectrum along various axes -- however, these axes can be understood:

1. Party

This is a question of degree of distance and authority. Who is doing the consenting? Is it the person/thing being acted upon or that will ultimately be affected, or another? What state of mind is the party doing the consenting in? Is the person his or herself whatever that means? Does it even have a sense of self or personhood? Ultimately the theoretically perfect case of this would be that the one being acted upon is a person who is the same one giving consent in a perfectly sound state of mind and with a perfect sense of self consciousness -- this is of course an impossible ideal. The impossibility of perfection here doesn't mean getting as close as possible isn't valuable, but it does doom the absolutist claims about consent and about the inability to obtain it being (in effect) intrinsically bad.

2. Information

How informed is the party who is giving consent? Again, this lies on a spectrum from complete ignorance to perfect omniscience of the act and all of its context and consequences -- the latter being again impossible. The impossibility of perfect information again doesn't invalidate the value of getting as close as we can, but again dooms absolutist claims.

3. Expression

How is the consent expressed, or is it expressed at all? The worst case here is an extremely generous "implied" consent where we just assume consent because a person has not communicated clearly enough that he or she does not consent and is not noticed to be physically opposing it, better if if that assumption is made at least on the basis that most parties do or would consent, better still is spoken consent improved by removing any possible ambiguity until we reach another (currently) impossible standard of infallible mind-reading. Yet again this impossibility doesn't invalidate the value of getting close, but yet again dooms absolutist claims.

As you can see, along every axis of variable relevant to consent there is a spectrum and an impossible perfect extreme -- perfect consent is impossible, so we're *always* dealing with various degrees of imperfect consent. Deontology fails to deal with nuance like this, preferring either-or circumstances, but that's not in line with the reality of consent in this universe. Consent is not an either-or absolute, and so it can not be an absolute standard for right and wrong behavior -- that of course doesn't mean it can't be a relative standard of more or less wrong actions depending on the degree of consent achieved, but such nuance is not something antinatalists are fond of and it's something intrinsically at odds with any strong antinatalist position.

Consent for Non-persons

The typical argument from anti-natalists goes something like this:

"A person can't consent to come into the world (or inevitable harm), so having children is always wrong"

The obvious rational reply is by analogy: "Infants can't consent to medical procedures so parents consent for them, how is that different?"

This anti-natalist objection to consent by-proxy or substitution is overwhelmingly contradicted in practice with medicine: When somebody is unconscious or unable to consent to medical care (or other immediate issues) we typically rely on professionals and family to consent for them. This isn't seen as a problem, so nobody is acting inconsistently by allowing the will-be family (like the mother) to consent for the birth of her beloved child.

To deal with that problem, anti-natalists may try to draw a superficial semantic distinction about consent, something like:

"The infant is a person and a non-person isn't, in order to consent for somebody you have to be able to identify who is being consented for"

There are many equally obvious problems with this reasoning.

The first and most essential problem (one that makes the point irrelevant and philosophically tone-deaf) is that while anti-natalists may attempt to refute the comparison by drawing an arbitrary semantic distinction between consent for an infant and consent for somebody who isn't born, this remains an arbitrary semantic distinction and nothing more -- it is not a *morally relevant* distinction. The anti-natalist claim completely misses the philosophical significance of substituted consent which is to act in the best interest of the person or not-yet-person when more explicit consent can't be obtained. The spirit of substituted consent is (along with all morally relevant considerations) maintained even if the principle can be argued not to apply on some kind of morally irrelevant technicality.

The second problem is the attempt of anti-natalists to have their cake and eat it too. To turn the semantic nitpick around, if we're dealing with a non-person then consent should not be an issue. Do they have a problem with people lifting rocks because the rocks can not consent to being lifted? We should expect not. If there is no person, then technically, consent should not be an issue: when the act is actually done there is no person, so the act can not be a violation of consent and thus can not possibly be wrong as such a violation. It's much like Epicurus' witty paradox about the fear of death (indeed fear of death itself doesn't make much sense, but a want of life does):

“Why should I fear death? If I am, then death is not. If Death is, then I am not. Why should I fear that which can only exist when I do not?"

-Epicurus

The person simply can not exist when the action to create a person is initiated. Only long after the act is done does a person come into being (in fact of reality, that fetus becomes a person very gradually into childhood) -- at that point consent arguably becomes relevant to actions on that person, but never to actions on a non-person which account for all of those actions prior to the person's actual existing. IF you can credibly point to the eventual person as a victim of the action whose consent was violated, then likewise that will-be-person can be identified for substituted consent in the same way it may be done for an infant or other person unable to consent in medicine.

The third and final problem is the transient and somewhat subjective nature of personhood itself as hinted to above; infants have little or no sense of personhood yet, so how can you identify a *person* in a vessel that does not yet have that capacity? And if we identify the person the infant might become from the cloud of future possibility, how is that any more credible than identifying the person an egg might become from the same? From an egg and a pool of sperm, to a fetus, to an infant, and even to an adult who may still fundamentally change as a person into somebody else, what we're talking about is a cloud of future possibility that is only constricted over time, but never to a certainty. Or instead is a person identified by DNA alone? Then what of identical twins and clones? What are the implications for tumors and abortions? What if the choice to bring a new person into the world pre-identified the egg and sperm used rather than relying on luck? Or what if that choice occurred after fertilization coming from the decision to abort or not? These are questions anti-natalists do not answer because they have no answers for them, all they can do is draw an arbitrary line without justification in attempt to prop up a dogma they have already decided was true without careful consideration.

Gambling Thief Analogy

In response to the claim that most people end up being reasonably happy about existing, commonly an analogy to stealing somebody's money and gambling with it (giving them the proceeds) is made, however this analogy fails in many important ways.

Most crucially, gambling is Zero Sum, often even negative sum (because the house always wins) and life is not. If you stole money from people to gamble, on average you would never be able to give them back more than you stole; this is statistically a harm, thus it's wrong to do because you will cause more harm than benefit. If you had a magic slot machine that paid out so substantially more than you put in, losses were incredibly rare, and the overwhelming majority of people you stole from to play the game for them were thankful for it, that would be very different.

If for some reason you were unable to ask consent to borrow a quarter from your friend's wallet to use in that magic slot machine which closes in one minute for a 99% chance of winning big for him on his behalf (something he or she would almost certainly consent to if it were possible), it would arguably be more ethical to take the risk on his or her behalf in order to yield a much greater benefit.

It's hard to imagine a realistically analogous scenario so pressing and odds so favorable that we'd be unable to ask for consent, so most of the time we're dealing with the *choice* not to ask for consent when it could be asked for -- that's another issue covered below.

Acting Without Consent

Even understanding that perfect consent is impossible, a broader challenge worth mentioning is the dogma that acting without consent (in any degree) is always wrong. The problems deontology has with consent have already been covered, but why might consent be important at all in a consequentialist framework?

It actually is typically inappropriate to do things without people's consent when they're capable of giving it even if you think it'll be OK, but the reasons for this are complicated and have more to do with ulterior motives that gambit would imply.

Because consent is usually a very reliable way to determine if something is in a person's interests or not, if it's easy to ask it eliminates the possibility of acting against those interests. Even if you're 99% sure somebody wants something, you don't have to take the risk they don't if you have the ability to ask. Therefore, if it's possible to ask we should, and that's what makes not asking (where possible) wrong. It's creating an unnecessary risk. This is not true where asking consent is impractical or impossible: the impracticality or impossibility of the query can justify the small risk.

To be clear it's not the acting without consent in situations where it would be easy to obtain consent that is necessarily wrong in itself, it's the failure to ask consent that was wrong. To bring this back to the implied gambit, if you ask first, whether the consent is given or not you are acting in the interest of the person so there is no harm (to that person) from asking. If you do not ask, you may be acting against the interests of that person, so likely the only motivation for not asking is selfish (that you WANT to do the action and don't want the risk of a "no" which would force you to stop or remove the plausible deniability that you were acting against the person's will).

Such is the case for sexual intercourse: the only reason somebody would not get consent is if he or she wants to do it regardless of consent. Consent is not asked because the aspiring rapist doesn't wan't the risk of confronting a no and either having to stop or having to actually admit to himself that he's doing a rape with no plausible way to deny it. There's an inherently selfish motive there which indicates a willingness to do harm for one's own benefit. It's almost always possible to ask for consent at some point, and sexual intercourse is almost never so urgent as require it go ahead without being able to ask -- thus the whole fixation on consent as the ultimately litmus for not being a rapist regardless of what you assume the person wants.

Of course, there are grey areas and exceptions to every rule. A woman whose husband had an accident and went into a coma from which he won't awaken, but whose sexual organs are still functioning, may wish to have a child with him knowing he wanted that too and trying to keep a part of him alive. He's no longer a person in any meaningful way, there's no way to ask for consent, or to wait for it, and yet it was understood that this is something he wanted. He might have changed his mind knowing he wouldn't be around to see them, but there's no way to know that. Is it wrong? Is it rape?

The bottom line is that there's nothing innate to consent, but rather the kind of motivations behind not asking when it's possible and the benefit consent has in increasing the probability that we're respecting somebody's interests. When it's not possible to ask consent and the probability that our actions are in line with the person's interests (or would be or will be interests) then the argument that consent hasn't been given is morally irrelevant.

So the only genuinely important philosophical question around bringing children into the world is whether it does more good or more harm, and that's an empirical one that has nothing innately to do with consent.

Negative Utilitarianism

Beyond flagrantly absurd arguments like Benatar's asymmetry, beyond unfalisifiable empirical claims of existence bias, and beyond very poorly thought-out arguments about consent, there's a much more complicated underlying issue of Negative Utilitarianism or Negative Consequentialism (different but for these purposes well just cover Utilitariansim since it's the typical example).

Extreme Ends

While much of antinatalism focuses on rights and contemporary suffering of each individual born, or those they affect through environment etc. without any end goal, a significant voice in anti-natalism is a consequentialist aim of human extinction (voluntary or not) or outright extinction of all sentient life. These ends based approaches have much more serious logistical problems that are either unaddressed or addressed with weak speculative science.

Human Extinction

Where other arguments are more focused on the suffering of humans who come into existence, or their right not to, arguments for human extinction may be promoted with or without those assumptions.

The core of the human extinction argument is a misanthropy that claims humans are an evil in the world, and it would be better for the world if we didn't exist -- in particular, that it would be better for the other sentient beings in the world with whom we do a poor job sharing the Earth and whom we treat poorly.

Not only are such arguments speciesist against humans, they're usually based on a romanticized idea of nature and ignore the reality of Wild Animal Suffering, or worse claim that the suffering of wild animals is unimportant and that only the natural aesthetic is important. Aesthetic arguments are hard to tackle, being subjective assertions of good based on personal taste, but those based on suffering that humans cause are simple to tackle: While it's clear that a world where humans are kinder to other beings and each other is better, it's unclear if a world without humans would actually be better. Human extinction would just open a new ecological niche which would likely be filled in a few million years (humans evolved in a blink of the eye in geological time). Hitting the reset button is not guaranteed to have a better outcome: what comes after us may be just as cruel or even more cruel than humans have ever been.

Denying this argument hinges either on denial of evolution, or an insistence that humans are uniquely cruel and that another primate that evolved to take our place (or masupial, or feline, etc.) would be kinder even if it evolves to fill essentially the same niche humans did -- a claim likely rooted in speciesism and irrational optimism about the natural world.

Because we have the potential to become better (as has been the trend in societal progress), it's better to keep trying with the possibility of improvement rather than resetting everything to zero and starting over when there's no evidence of better odds for the next go-around. The odds may even be worse the next time, because the next species may lack the readily accessible resources that humans have already exploited, limiting its technological and social development -- that means this may be the only chance Earth has for possibly hundreds of millions of years to develop conscientious caretakers. There's no reason to believe humans are uniquely bad or that the worst of it will last indefinitely.

As an extension to the Human Extinction argument, based on wild animal suffering and the potential for another human-like being to just evolve in our place, some argue for the involuntary eradication of all life on the planet (or even all life in the universe). See Efilism.

Efilism

Efilism, the ideology that all sentient life is bad. It's distinct from antinatalism in that not all antinatalists are efilists, but linked to it because Efilists are a kind of antinatalist. Efilism is often argued (and argued well) to be the only logical conclusion of most antinatalist philosophy due to the failure of voluntary antinatalism (see dysgenics), and the significance of suffering of other life forms that can't consent to annihilation or abstain from reproduction willingly.

There will likely always be a fringe ideology that believes life is inherently bad and wants to forcefully wipe out all sentient life on the planet or even in the entire universe. You may even agree with that position. However, believing that 99% or more of the population will in the foreseeable future see this as anything but a comic book supervillain motivation is naive and bordering on mad.

Its inherent unpopularity, at least today, is why like a comic book supervillain any attempt to put it into practice is likely to fail and only cause a large amount of suffering in the attempt. Even an Efilist would likely agree that the most likely result of an attempt (like releasing a virus) of merely killing a few people and maiming or sickening millions without successfully wiping out the population only makes things worse. The fundamental obstacle to Efilism is that it's a non-starter even if it were true in principle (which is debunked in other sections of this article). Here we'll skip over the philosophical objections -- many, varied, and already covered in other sections -- and touch on the impracticability of the thing.

Were Efilists to succeed in wiping out sentient life somehow, there are also serious questions about how useful that is; due to evolution, it will only be a matter of time (and a very short one in geologic time spans) before new sentient life emerges. That new life then has a lengthy struggle in millions of years to higher intelligence, and potentially many tens of thousands of years of turmoil, war, and suffering as ancient human civilizations experienced. It's not clear how "hitting the reset button" is superior to leaving things alone, and it's definitely not clear how it would be superior to actually applying that effort to progressive causes of making the world suck less.

In response to this an Efilist may regale you of tales of sentry robots that watch over planets exterminating complex life as it appears, and of course they self-replicate and self repair and travel the universe wiping out and keeping wiped out life wherever they find it until the heat death of the universe. What happens when they break down or malfunction? Well don't worry, they have synthetic intelligence and they can problem solve. OK so you just made a new sentient creature to replace the old ones exactly how is this an improvement if all sentient life is suffering? Well they're programmed not to suffer. So then not all sentient life is suffering and it can be fixed? Oh, wait. Efilism is a dead-end philosophy.

The point is, as elaborate and convoluted as this space opera becomes there remain unsolved glaring inconsistencies that beg the question of whether any of this is a good idea evenif it were plausible, and that if we had this kind of hypothetical technology maybe we should just focus on making what we have better like the transhumanists do -- arguably still kind of nutty to most people, but minus all of the anti-life comic book villain style evil that people find deeply unsettling about Efilism.

Sentry Robots

Even assuming that extinction of humanity or even all sentient life would be a good thing, trying and failing to achieve those ends would have a much higher probability of only contributing more harm (see Human Extinction).

Setting aside the current technological implausibility, Sentry Robots are proposed as a means of preventing nature and evolution from undoing what human-extinctionists or efilists worked so hard for. Depending on who designed them, they're made to stand guard and either on Earth or throughout the universe continually destroy life: all life, all sentient life, or all human-like life/intelligence which passes the threshold for being considered evil and threatening the aesthetic of nature.

The idea of sentry robots being reliable poses a number of serious problems:

Isolation

The world or universe can't be reliably contained in a small bubble; there's always the chance of outside forces with differing beliefs interfering with and even destroying these sentries. If the robots are the seek out and destroy kind, then life with any significant level of technology will also likely defend itself; here the sentry robots may or may not be successful. If unsuccessful, they would have just attacked and planet and caused large amounts of suffering with no good outcome.

Just as these viewpoints are unpopular on Earth, there's every reason life elsewhere in the universe has similar selective pressure against voluntary extinction, and very likely even for expansion and colonization. Even a Sentry Robot confined to Earth would have no guarantee that for the coming BILLIONS of years no life seeding robot hostile to its mission would challenge it -- and very possibly one far more advanced than its own defenses.

A Sentry Robot could plausibly delay the inevitable, but the time-scales at play here are incredibly vast and bring neighboring star systems very close even at sub-light speeds.

You would have to be completely certain that either: A. There is no other life in the universe B. Any intelligent life must naturally agree with efilism or equivalent because logic C. Your robot is the most advanced and powerful possible and nothing could ever threaten it

None of these are reasonable beliefs to hold with any level of certainty.