Antinatalism

While our members may have various views on the topic, the Philosophical Vegan community does not endorse the anti-natalist view, as in most issues outside of veganism taking a neutral position on natalism (reproductive choice, neither assigning blame or condemnation to those who have or do not have children). However, antinatalism is a belief system that appears more prevalent in the vegan community than in the general public, and is of philosophical interest here as a significant point of contention between vegans, particularly when it is introduced into vegan discourse or activism. Herein we will cover what it is, what it isn't, and outline the best and worst arguments on the issue along with the practical matters of involvement in vegan activism.

Contents

Definition

Anti-Natalism is the general or universal belief that there is always net negative value to procreation, to be contrasted with the belief that procreation is wrong in specific cases.

While there are specific cases where pretty much all people are anti-natalist in a limited sense, like during wars or famines where the outcome is most clearly bad for the child, that in itself is not anti-natalist in the broad sense (the sense which this article discusses). Likewise, pretty much all vegans hold or even promote limited anti-natalist positions with respect to farmed animals and believe breeding these animals for a life of suffering and an early death is wrong, again that is in itself not anti-natalism (as per the discussion in this article). Others who identify as antinatalist may be more flexible and have inclinations that it is usually but not always wrong to procreate, which is not the primary focus of this article.

Anti-natalists (as discussed in this article) do not have objections merely to specific cases of procreation where inordinate harm is involved, but to procreation generally even from healthy, secure, well adjusted parents; and even to socially and environmentally conscious parents who would pass those values onto their children.

Because it is an absolute and universal claim, antinatalism is most likely to be grounded in Deontology (also referred to as dogmatic ethics), and not based one Consequentialism which considers outcomes and will in practice result in exceptions to rules -- which is to say antinatalism is not usually a practice about best outcomes (where there will always be exceptional cases), but about avoiding violating certain rights. This absolutism may be contrasted with the Definition of Vegan which is provisional rather than absolute in prescription (containing language like practicable and possible), and the belief of most vegans that it is not *always* wrong to eat meat (such as for people with food access issues). There are consequentialist anti-natalists, by necessity of a negative-utilitarian-like variety, but this may be on a technicality (because everything has net negative value in those frameworks) because there can always be possible cases where having a child is a smaller negative than not having one (a specific child being most likely to prevent more suffering than he or she causes or experiences). This will only be discussed briefly in this article.

To be clear, most antinatalists (like most people of any philosophical inclination) aren't familiar with the distinction between deontological and consequentialist arguments, and will likely subscribe to and promote both forms of arguments without any clear affiliation to one or the other -- in practice you will see an argument for the rights of the unborn to consent to birth along consequence based arguments on climate change. The problems and merits of all of these individual arguments will be addressed here, but it should be understood that antinatalism as the philosophical position discussed here is a strong position and not one simply provisional upon circumstance like the current climate crisis. As a community that focuses on consequentialism, Philosophicalvegan doesn't endorse antinatalism, but as any committed antinatalist will tell you: a person who is only provisionally against birth because of the current climate crisis (or some other temporary state of affairs) is not an anti-natalist any more than somebody is a vegan if he or she doesn't eat meat only the only meat available is a product of factory farming.

Being vs Promoting

Before addressing the common philosophical and empirical arguments that may suggest antinatalism is correct or incorrect as a position, it's important to make the distinction between being an antinatalist (personally believing in and following antinatalism as a philosophy) versus advocating or promoting the position to others as part of activism. One does not necessitate the other, as there are no deontological mandates for proselytism -- deontological rules are typically prohibitions. So while an antinatalist may be forbidden to lie about his or her beliefs, that doesn't mean volunteering the information or arguing for it is compulsory.

Somebody may be an antinatalist in the philosophical sense that he or she believes procreation is always morally wrong (or virtually always wrong today, antinatalist adjacent, see definition above), and perhaps lives accordingly, but that doesn't necessarily mean it's a good idea to promote that position today. By analogy to the Abortion issue, this can be much the same way as somebody could personally oppose and never have an abortion, but keep that private to avoid shaming others and support pro-choice legislation to prevent "back-alley" abortions and other social issues that prohibition can cause.

For a consequentialist antinatalist-adjacent, or one following a mixture of deontological and consequential reasoning (usually where deontology answers absolute questions and consequentialism dictates behavior in cases deontology doesn't) there are a number of pragmatic reasons why an antinatalist/adjacent may chose to remain silent about the position. Such a person may even understand it to be wrong to promote antinatalism in the modern context due to the consequences of promoting it. These reasons go beyond the personal and professional consequences of promoting an unpopular or offensive ideology (like ruining relationships or getting fired) to compelling moral reasons why a believer in antinatalism might want to leave these ideas on the back burner -- if not because they're inherently problematic in terms of their consequences, then in the least because the world is not ready for them yet (that doesn't mean it's philosophically wrong, but imagine promoting veganism in the Paleolithic era when cannibalism was still a hot button issue).

Inefficacy

As a long-shot cause, antinatalism is far out there today (beyond veganism and other already difficult to promote causes that are otherwise gaining support).

The desire to have children is very strong, and may even be instinctual and impossible or impractical to substitute -- this is in contrast to veganism, particularly in the sense that there's not necessarily any desire to eat meat that can't be replaced by alternatives. Mock meats fill any reasonable culinary of cultural preference, and modern nutritional science that makes it possible to eat vegan (e.g. B-12). There is no equivalent to mock meats for the experience of having and raising children for people (pets appear to be poor pseudosatisfiers in this respect).

Antinatalism is an inherently more difficult ask for people who don't already prefer being childless (for whom the argument is not necessary).

In the sense of a long term approach, there's also bad historical precedent for ideologies like antinatalism. While rights movements (like anti-slavery, women's rights, anti-racism) have had a gradual and multi-generation march to progress, ideologies and religions that forbade reproduction do not have very long lives or ability to spread. Such ideologies have a very poor ability to expand on the progress of the prior generation or pass on values. While values can move laterally between acquaintances or even strangers through speech and argument (or at the point of a sword), the dominant vector for ideologies is still through lineage (with very gradual change), and an ideology that forbids that is competing against those that promote it ("go forth and multiply") -- this puts ideas like antinatalism and any that are bundled with it at a competitive disadvantage against those that are neutral or positive toward procreation.

While being a long shot isn't necessarily a good reason not to promote a cause on its own, it is a good reason in the presence of other competing causes that have better odds of doing good (and less chance of doing harm by turning people away). This is due to something called opportunity cost -- losing the opportunity to do the good thing you could have otherwise done. Promoting one cause typically comes with the opportunity cost of not promoting another or promoting it less effectively, and this is even more the case when a cause is so controversial, thus why promoting antinatalism may take a necessary backseat as a case of moral priority to promoting more effective causes that more people agree with like ending wars, green energy, and reducing human reliance on animal products. This is, incidentally, why some vegans choose to practice veganism but only promote reducetarianism (the reducetarian message may be better received in certain demographics while "go vegan" may put people off).

A frequent retort to opportunity cost is the intersectional claim of advocating all things together being more effective, but theories of intersectional activism don't come with evidence of that claim, and conventional wisdom (the null hypothesis) says that trying to do more than one thing at a time and generalizing will usually result in lower efficacy to all goals. When it comes to activism this is particularly true because a narrower goal can recruit more people in support of it as shown in issues such as bipartisan political causes -- finding one issue where you can get a lot of people on board. It's also worth noting that modern intersectional activism (in so far as it has any momentum to exploit) is aligned with reproductive choice and against shaming those choices, so bundling antinatalism with that results in conflict and contradiction. Worst case, trying to bundle issues can result in guilt by association that harms the other issues from the presence of a more controversial issue.

Association

While some activists attempt to take an intersectional approach to promoting things like veganism and antinatalism side by side, the less palatable point to any given audience may cause harm to the more acceptable one -- in short, as a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, so is a bundle of ideas (particularly restrictions) only as appealing as its most objectionable part.

Pairing veganism with antinatalism inevitably makes it harder to spread the vegan message to those who do not already agree with antinatalism, and for those who do agree (an incredibly small minority) the "preaching to the choir" aspect is unnecessary.

To explain by way of a hypothetical: imagine promoting veganism along side abolition of slavery in the early 1800's. The vast majority of people would have laughed at you, or dismissed your abolitionist arguments, even using you as an example of the absurd slippery slope of equal rights (thus harming other activists' work too). Your abolitionist work would have been harmed by your promotion of veganism, and your promotion of veganism in that context would likely not have helped any animals or even harmed people suffering under slavery by creating the association, causing that addition to be a net harm to your and others' outreach and preventing you from doing good (and even meaning you cause net harm by trying to do good). The correct approach would have been to *be* vegan yourself, but only promote abolutionism. Even if philosophically correct and arguably conceptually related, antinatalists need to carefully consider whether antinatalism inserted into vegan activism today serves to help animals or impede activism thus harming animals.

Guilt by association is typically a fallacy, and yet it's a matter of fact that many people naturally think that way. Activists need to act in ways that are compatible with how people DO think and not with how they believe people SHOULD think in an ideal world (one we don't live in). When vegans promote other radical positions that can put people off, and particularly when they present them as part of veganism, they risk alienating people from veganism in the process. Thus a person who may have gone vegan may be put against it by the bigger ask of never having children if he or she wants to join the movement.

This harm only increases as the antinatalist position becomes stronger and even endorses the use of force.

Dysgenics

Dysgenic

exerting a detrimental effect on later generations through the inheritance of undesirable characteristics.

-Oxford English Dictionary

Dysgenics here is used broadly to include effect on all heritable traits, both genetic and otherwise; whether nature in terms of genetics, epigenetics, or nurture in terms of early childhood environment or other unknown factors. Eugenics is controversial, particularly as it's usually a non-evidence-based talking point of racists, but consideration for dysgenics isn't the same as promoting eugenics. It should be uncontroversial that whether you believe offspring carry on genes or learned behavior of parents, there is a connection there which in theory may be magnified when certain conditions are met. A pop cultural example would be the movie Idiocracy, which comically explores the consequence of intelligent people having fewer children, although in reality the effect is very weak at less than an IQ point a generation[1].

For a less incendiary example, if people who liked collecting coins had ten times more children than those who didn't, we could reasonably expect coin-collecting to become the dominant hobby on Earth in a few generations. It might not be a problem if coin collecting took over as the most popular activity of humanity, but what if there were a disturbing correlation like 99% of coin collectors also ate live kittens? Correlation doesn't always mean causation, but this should be something to give us pause (this is an absurd hypothetical of course, there is no evidence that coin collectors eat live kittens).

It might be implausible that coin collectors have more children than non-coin collectors, but it is not a stretch to say that pro-natalists likely have more children than anti-natalists. We might need to ask what kind of correlations exist therein. Philosophical vegan doesn't claim knowledge of any specific correlations to antinatalism, but antinatalists seem to believe antinatalism is correlated with a number of positive personality traits, so this is in particular something antinatalists should consider with respect to unintended consequences.

It's an inevitability today that not everybody is going to come on board with antinatalism willingly. IF a proponent of antinatalism is against forced sterilization, forced abortions, imprisoning people for disagreeing with the ideology, etc. (things that most sensible people are against and that most antinatalists are against due to deontological prohibitions against these) then regardless of the size of the antinatalist campaign there will still be people reproducing while the antinatalists are not immortal.

The selective pressures with anything that acts directly on reproduction like this are substantial. If there is any inherited component (be it genetic or nurture) to the desire to have children, and/or even any inherited component (genetic or learned) to the tendency to accept and follow antinatalism philosophically (like higher compassion, intelligence, impulse control, etc) then any broad campaign for elective antinatalism in a population would have a dysgenic pressure against those traits that are associated with antinatalism (if they indeed are) and in favor of the presumably negative trait of desiring children and traits claimed to be associated with it (unintelligent, low compassion, low impulse control, etc.). To be very clear, the Philosophicalvegan community does not endorse the claim that "breeders" are stupid impulsive and cruel, but if antinatalists believe there is any truth to a correlation with these traits and rejection of antinatalism then they need to account for that in their calculus when it comes to public distribution of antinatalist messages.

In any case with some form of heritability the result is the same: the kinds of people who follow antinatalism are selected against, and the traits tied to that go with it which could (if antinatalists are correct) be a less compassionate, less intelligent, more impulsive population that has a much stronger innate desire to have many children -- enough so that the anti-natalist movement ultimately creates the conditions for its own demise, and we're even worse off than we were before by their own metrics.

None of this is to suggest support for eugenics, only outline a likely unintended consequence following from the beliefs about "breeders" that antinatalists have. Any pressure for antinatalism, when applied selectively (people choosing to follow it), acts as any Darwinian pressure does. The only option that avoids this selective pressure is one that involves a substantial measure of force (e.g. forced abortions, sterilization, imprisonment, execution etc.) applied broadly and involuntarily across the population, which isn't something most vegans would accept and certainly not something most people would accept (even most antinatalists do not accept this). If you start promoting force with antinatalism then the efficacy of that advocacy drops even more dramatically while the negative associations grow and harm anything the ideology touches. That doesn't stop a fringe from supporting that view (see Efilism), but it's something to consider if you don't advocate extremism.

So even if it is wrong in some philosophical sense to have children, it's very plausible that the net effect of promoting that view may also have harmful consequences which outweigh any nominal benefit, or result in an effect counter-productive to the goal. It's possible to not have a goal if the antinatalist position derives from a deontological rule that having children in and of itself regardless of consequence is wrong, but the dysgenic effect should be an unintended consequence that anybody of a remotely consequentialist mindset should be wary of when considering promotion of antinatalism (even if consequence takes a back seat to deontology, remember that deontology doesn't demand proselytism). Antinatalism is fairly unique among ideologies in this counter-productive effect because it uniquely affects reproduction in an extreme and singular way.

Benatar's Asymmetry

Benatar's Asymmetry is likely the most popular argument among self-identifying antinatalists, but to be clear it's also probably the poorest argument there is for antinatalism (incidentally, it's also one of the Bad Arguments for Veganism). Many philosophers outside the Philosophical Vegan community (Even antinatalist-leaning philosophers) do not hesitate to recognize the serious problems in Benatar's asymmetry from any number of angles, and for anybody interested these free access published criticisms may be worth checking out:

- Julio Cabrera: Quality of Human Life and Non-existence[2]

- Erik Magnusson: How to reject Benatar's asymmetry argument[3]

- Fumitake Yoshizaw: A Dilemma for Benatar’s Asymmetry Argument[4]

We cover Benatar's Asymmetry as an overview in this article due to its popularity, and doing so as the first argument is both because of its popularity and to get beyond it so we can address more potentially credible arguments (such as the empirical environmental arguments for a smaller population, or more interesting philosophical arguments). To be very clear, we don't mean to represent Benatar's Asymmetry as the gold-standard in antinatalist argumentation (which would be effectively straw-manning the entire movement of antinatalist philosophy); to the contrary, every other argument addressed on this page is more worthy of exploration and careful consideration. While we strive to take a neutral position on issues outside veganism, and are neutral on natalist topics (as noted in the intro), we do take a hard stance against fallacious and invalid philosophical arguments because they create rhetoric and distraction rather than furthering important conversations in ethics.

An eloquent summary of the relative merits of antinatalist argumentation:

Antinatalism (applied to modern humans) is a neat illustration of how the reasoning someone follows to arrive at a conclusion can tell you more about the person than the conclusion itself tells you.

If you're an antinatalist because you think people experience more suffering than pleasure, then I disagree, but I think it's an empirical question, and I can imagine your position being correct.

If you're an antinatalist because you're a negative utilitarian, then I think the axioms of your moral system are deeply unappealing, but at least not fundamentally inconsistent.

If you're an antinatalist because of Benatar's asymmetry, then I think you've fallen for one of the most flagrantly ridiculous arguments in modern moral philosophy. -Evan Sandhoefner (img)

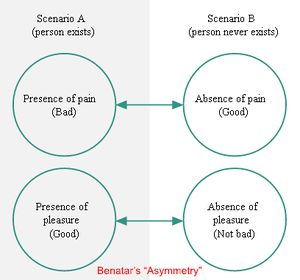

Qualitative Benatar's Asymmetry

Benatar's asymmetry claims on intuition that the absence of pain is good, but the absence of pleasure is not bad.This is related to negative utilitarianism, which bases assessment only on pain and ignores pleasure entirely. The apparent distinction is that Benatar doesn't deny the positive value of pleasure during existence as negative utilitarians do (which makes it more intuitively palatable), but this may be a meaningless distinction if you only look at qualitative (all or nothing style) comparison as in canonical diagrams (and as he seems to prefer):

My view is not merely that the odds favour a negative outcome, but that a negative outcome is guaranteed. The analogy I use is a procreational Russian Roulette in which all the chambers of the gun contain a live bullet. The basis for this claim is an important asymmetry between benefits and harms. The absence of harms is good even if there is nobody to enjoy that absence. However, the absence of a benefit is only bad if there is somebody who is deprived of that benefit. The upshot of this is that coming into existence has no advantages over never coming into existence, whereas never coming into existence has advantages over coming into existence. Thus so long as a life contains some harm, coming into existence is a net harm. -David Benatar[5]

That is, the absence of life is always qualitatively "good" to Benatar, but the presence of life may be "good" or "bad" (depending on how lucky you were based on how much pleasure or pain there is). The certainty of good, Benatar believes, always outweighs the chance of it. The way he achieves this dichotomous result is through all or nothing style analysis (good life or bad life) with no concept of gradation or weighing the magnitude of good or harm in different scenarios against each other.

There are essentially two methods by which the results can be interpreted to arrive at the absolute conclusion Benatar wants.

- Never quantify good and bad to begin with (see explanation here)

- Quantify it to get a scalar value of goodness or badness for the life (something on a spectrum), then sanitize the results afterwards to a good/bad boolean style value (either negative or positive, nothing in between) for simple qualitative comparison

Benatar does the latter in order to preserve the appearance of recognizing that some lives are or could be good for intuitive appeal. It is proposed to work as such:

Consider Bob, who has a wonderful life filled with happiness (10 happiness), but he gets a paper cut once (1 pain).

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 10 Pleasure | 10 | 0 |

| Pain | -1 | 1 |

| Total | Good | Good |

Because the good was larger than the bad, the life is considered a "good" life. But because good is also larger than bad for non-existence, that's also considered "good". Because the quantities have been scrubbed away (discarding the information that the life is more good than the non-existence is bad) in favor of dichotomous qualitative statements, Benatar's claims of certainty would follow only from saying they're both good, so it's a wash.

However, because not all lives will be good, there is a risk of existence being worse than non-existence.

Consider Tom, who has a terrible life filled with misery (10 pain), but he gets a tasty cookie once (1 happiness).

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Pleasure | 1 | 0 |

| 10 Pain | -10 | 10 |

| Total | Bad | Good |

Here the magnitudes are again scrubbed away, but one is bad and the other is good. Life in this case would be inferior to non-existence.

So, Benatar argues, because the best case is a good life and in those cases non-existence is also good, but in the worst cases there's a bad life where non-existence would be good, betting on non-existence being superior on average is not just a good bet but a sure thing.

Because you fail to consider the magnitude of good and bad, and only look at a dichotomous result, some lives must inevitably be assessed as bad and non-existence is always good. Thus Benatar's Asymmetry (if it works as he claims) makes superfluous the otherwise crucial empirical arguments about the balance of pleasure and pain in life.

Quantitative Benatar's Asymmetry

A serious problem is that despite Benatar recognizing the fact that these things can be quantified and weighed (he recognizes a life can be net bad even if there's some good in it), he is unwilling to engage in quantitative analysis of the goods and bads in life vs. unlife. This makes his claims inherently inconsistent, and probably also intellectually dishonest if he uses arguments that are inconsistent with his own when it suits him.

If we examine quantity of good or bad, the effect is that the asymmetry argument engages in double counting for pain without justification, but that it isn't impossible for life to be better than non-life. That is, it does not make the empirical arguments unnecessary as Benatar claims.

As an example, consider the existence or non-existence of Bob, who has a life with 5 units each of pleasure and pain (presuming we have a good method to measure it):

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 units Pleasure | 5 | 0 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 5 |

| Total | 0 (neutral life) | 5 (good non-existence) |

Here Benatar's asymmetry (no matter how it's assessed) would says that it's better than Bob not exist than exist.

Even with a comparatively good life, this is the case:

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 6 units Pleasure | 6 | 0 |

| 4 units of Pain | -4 | 4 |

| Total | 2 (Good life) | 4 (Better non-existence) |

Benatar's asymmetry would even claim that people with good lives, including significantly more pleasure than pain, would be better off not existing, which is a very serious violation of intuition, but at least follows from his premises.

Where the claim meets a contradiction is that this is not always the case in a comparative assessment. In order to even break even in quantitative analysis, a life would have to contain twice as much pleasure as pain. However, contrary to Benatar's claims, if a life is sufficiently happy, it obviously IS better than non-life even if we blindly accept unjustified double counting of pain; that is if the two scenarios are assessed honestly with a quantitative comparison rather than ad-hoc sanitization of the results.

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 10 units Pleasure | 10 | 0 |

| 2 units of Pain | -2 | 2 |

| Total | 8 (Very Good life) | 2 (Slightly good non-existence) |

Here existence is clearly preferred (offering more good) than non-existence. So if Bob lives a great life of happiness and contentment and gets a paper-cut once, it IS better that he had lived than not. This should be intuitively obvious, but even if it isn't intuitively obvious it's the only honest conclusion following from a consistent application of measurement standards. Benatar is simply wrong that it is guaranteed that life will always be less than non-life, the result is leaving the question of whether we should or should not have children up to empirical contention. It is plausible (or at least an open question) that a significant number of humans and non-human animals live lives they would consider at least twice as happy and pleasurable as they are sad, and so if used consistently, an honest interpretation of Benatar's asymmetry does not result in broad antinatalism.

The only way Benatar's asymmetry comes to the certain conclusions he wants (that life is always a bad gambit vs. non-life) is to engage in not one, but two forms of unjustified manipulation: Double counting pain AND assessing the results only qualitatively (good or bad) rather than quantitatively (a spectrum).

Alternative Qualitative Asymmetry

Never-Quantified assessment is one viable alternative to Benatar's approach may be suggested to preserve the asymmetry without the appearance of intellectual dishonesty.

This is the alternative method of assessment mentioned in the first section (Never quantify good and bad to begin with) and what makes it at least potentially more intellectually honest because it could be paired with the belief that pleasure and pain are inherently unquantifiable and incomparable.

Like negative utilitarianism, though, this approach is a serious violation of intuition and it would cost the most appealing aspect of Benatar's argument vs. true negative utilitarianism (Benatar's recognition that some lives could be good).

As an example:

Consider Bob, who has a wonderful life filled with happiness and pleasure, but he gets a paper cut once. The happy life merely counts as "pleasure" which is good, and the paper cut counts as "pain" which is bad.

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| Pleasure | Good | Neutral |

| Pain | Bad | Good |

| Total | Neutral (good+bad) | Good |

Because there is no quantification at all during life, all lives inevitably result in a neutral output, or "good + bad".

Consider Tom, who has a terrible life filled with misery and pain, but he gets a tasty cookie once. The life of misery merely counts as "pain" which is bad, and the cookie counts as "pleasure" which is good.

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| Pleasure | Good | Neutral |

| Pain | Bad | Good |

| Total | Neutral (good+bad) | Good |

Again, the exact same result.

Here a life of happiness with one paper cut looks the same as a life of misery with one tasty cookie as an exception. All lives have good and bad, but all non-existence just has good, so the latter always wins in a comparison (but may not be compelling, more on that shortly).

Such an asymmetry paired with a belief in the inherent quantitative incomparability of pleasure and pain could result in an apparently consistent outcome. Of course, it's one that claims a life of suffering isn't any worse than a life of bliss because they both contain pleasure and pain: such a claim is a profound violation of intuition unlikely to be taken seriously by anybody at all, and it's not the canonical Benatar claim (so it's beyond the point here).

The consequences of such beliefs would also be very troubling: to not bother preventing (and not worry about causing) additional suffering for living beings because it makes no difference. A further consequence to antinatalism limits the compelling force of those antinatalist claims themselves: antinatalists could no longer claim that having children is bad, only that it's neutral. If they wanted to attempt to claim having children (neutral) was bad on the basis that the lack of good (from having one less non-existing person) was bad, then the argument would contradict its own premises -- that the lack of good is *not* bad (unlife would also become neutral, arguing only for nihilism and not antinatalism).

The best an antinatalist could do is assert that people are compelled to always do good instead of neutral things (which would be a very strong claim), but even were this asserted, the problems of Assertions(next section) would still be relevant. And the claim of quantitative incomparability of pleasure and pain has empirical challenges.

Asymmetry as an Assertion

There are many practical problems with the asymmetry argument, but the most substantial is the fact that these argument are based merely on assertions without sound justification, and they are assertions of the kind which the opposite can be just as credibly claimed with significant implications (negation and reversal of all conclusions).

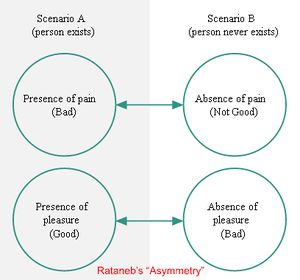

In this case, the opposite assertion is the Rataneb's Asymmetry: the absence of pleasure is bad but the absence of pain is not good. (See image, right) Any half-decent debater can twist words and appeal to emotion to fabricate any number of spurious intuition-jerking arguments ad hoc to support this absurd asymmetry, for example:

When we experience a pleasurable event, that's good. But when we miss out on pleasure, like in the case of a father who dies before seeing his daughter's wedding, we understand that is bad even thought he wasn't there. It's a missed opportunity for happiness.

Similarly when we experience pain, that's bad. The asymmetry arises with missed pain, because missing out on pain is not good, it's just neutral. If you're not alive and not in pain that doesn't feel like anything at all.

It may sound convincing when it's phrased cleverly, and if you don't think about it (which is likely if you want to believe in this argument) but the argument is vacuous.

The consequences of accepting this inversion (the Rataneb's Asymmetry) would suggest that even a life of substantial net suffering (as in modern animal agriculture) to possibly be better than no life at all if as outlined in previous sections it effectively double-counts pleasure. In the case of dismissing quantitative analysis entirely (using the same all or nothing extreme Benatar favors), then even the worst factory farming would always be guaranteed to be morally good for giving life if the animal inevitably experienced some kind of small pleasure at some point in life (e.g. a hatching chick enjoyed the first steps, then everything else was suffering).

Because Benatar's asymmetry is based on no reason whatsoever (it hinges only on the audience's willingness to believe it and the presenter's persuasive eloquence), there's no reasonable argument a proponent can make against somebody claiming the precise opposite to promote any abhorrent conclusion. Such a Rataneb's Asymmetry argument could be used to promote the most cruel factory farms, or even promote procreation (and denial of birth control) in cases of impoverished, wartorn or disease-stricken areas which might actually result in substantial human suffering.

When you throw out the idea that the amount of pleasure and pain matters, you can promote any kind of position based on ad hoc assertions of asymmetry, and these assertions can be just as easily turned on their heads to advocate the precise opposite view.

The practical consequence of embracing such an arbitrary ad hoc assertion as Benatar's asymmetry is that, when faced with the counter-assertion (Rataneb's Asymmetry), an interlocutor is either forced to argue as a hypocrite with a dishonest double-standard (as Benatar himself apparently does), or to abandon the most powerful argument against the opposite assertion and fall back like a child in a school-yard argument on the counter-assertion of "no, you're wrong and I'm right because I said so. Infinity".

An opponent of the asymmetry, however, can criticize the grounds for the assertion itself, and argue that similar treatment should be given to pleasure and pain, and that quantitative assessment is crucial to understanding comparative value (otherwise we are faced with an impenetrable nihilistic sameness that negates the purpose of moral discourse).

Symmetric Alternatives

There are symmetric alternatives which consider pleasure good and pain bad, and the absence of pleasure and pain to both be neutral or both have the inverse value relative to the would-be experienced states in life. These come to identical conclusions with respect to which scenario are better, and differ only in degree of difference.

Compare neutral:

| Absence=0 | Existence | Non-Existence |

|---|---|---|

| 5 units Pleasure | 5 | 0 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 0 |

| Total | 0 (neutral life) | 0 (neutral non-existence) |

| Absence=-x | Existence | Non-Existence |

|---|---|---|

| 5 units Pleasure | 5 | -5 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 5 |

| Total | 0 (neutral life) | 0 (neutral non-existence) |

A good life:

| Absence=0 | Existence | Non-Existence |

|---|---|---|

| 10 units Pleasure | 10 | 0 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 0 |

| Total | 5 (good life) | 0 (neutral non-existence) |

| Absence=-x | Existence | Non-Existence |

|---|---|---|

| 10 units Pleasure | 10 | -10 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 5 |

| Total | 5 (good life) | -5 (a bad non-existence) |

Note that the difference between the latter set is larger, at 10 net points difference rather than 5. However, the overall prescription (to choose life instead of non-life) remains the same. Similar results are true for bad lives, where the bad life is more bad.

Here there is double counting, but because the double counting exists for pleasure and pain the outcome is not meaningfully different, and it doesn't create an unjustified asymmetry.

Therefore, there is no significant drawback to using either of these approaches, and you can freely engage in discourse with your interlocutor's preference (be that neutrality of non-existence or inverse relative value). Once established as symmetric, the only issue is scale.

Existence Bias

In the context of anti-natalist argument the claim of "existence bias" is an unfalsifiable but seemingly empirical claim that we are biased about our own existence being good or happy, so we're perpetually in error when we assess that we enjoy life/that we are generally happy about having been born, and instead are in fact subject to far more bad than good in life.

Optimism Bias vs Pessimism Bias

The first issue is that this isn't necessarily an "existence bias" which is something that sounds like it would be objective and irrefutable because obviously we exist -- rather what is being alleged is an "optimism bias". Fundamentally, this is the same kind of semantic shenanigans as we find with Benatar's asymmetry; once the real spectrum of possible biases have been considered, we can see that both optimism AND pessimism biases may be at play and there's no reason to assume that the average person is any more under the sway of an optimism bias than the average anti-natalist is under the sway of a pessimism bias; both are just assertions without evidence that are not conducive to conversation or a honest assessment of the issue.

An anti-natalist arguing on the basis of "existence bias" (optimism bias) may claim it has to do with evolution, but such a claim is a perversion of evolutionary theory. Animals evolve to actually be more suited to their environments, not merely to survive under delusions that they are more suited to their environments. If evolution has made animals more content or happy with their circumstances for purposes of survival then this is not an existence bias (or optimism bias), it's a valid modification of the baseline. Events like hunger, cold, or injuries don't have objective metrics of negative value, but rather it is the experience of those conditions that are evaluated and given value by those who experience them. If there is a bias in any direction it is not provided any credible evidence by evolutionary psychology.

Unfalsifiable Prescriptions

It's a serious problem to make controversial and forceful prescriptions for others based on unsubstantiated (and particularly unfalsifiable) claims about empirical reality. To demonstrate why this is, the very opposite can be just as easily asserted, or even apparently absurd (but still unfalsifiable) claims about factory farmed animals experiencing more pleasure than pain despite appearances: a carnist may just as well claim that the farmed animals are just stressed because they have "pessimism biases" but in fact are experiencing far more goods than bads and so the industry is moral. Assertions like this are not productive to discourse. However, the principle of why this kind of unfalsifiable claim is categorically problematic is difficult to explain to committed anti-natalists (like anybody who has taken a strong position on something as part of personal identity).

Sometimes it's helpful to understand it by analogy to other problematic cases of counterproductive political discourse today, eg. on the abortion topic.

Reliance on Hedonism

Fortunately the force of this claim, if true, also depends on on a hedonistic value system (as opposed to a preference system) where pleasures and pains can be objectively weighed against each other to come to a conclusion as to whether your life has net negative or positive value to you regardless of how you actually feel about it or what your interests are. This hedonistic claim is one that can be attacked very persuasively for most people using simple thought experiments that challenge intuitions on this point:

The "pleasure pill" challenge that puts a person in a mindless euphoric coma to maximize hedonic pleasure

It can also be challenged philosophically on its arbitrarity in light of claims of objectivity: Why is this particular electrochemical signal bad? Why is another good? What about species with different neural architecture? And finally, the claim can be challenged empirically based on its connections to psychological egoism. Challenges to hedonism can be found in more detail in Hedonism vs Preference.

Within a preference framework, such claims of Existence Bias or Optimism Bias don't make any sense unless you're talking to somebody who claims to only prefer maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain (in which case you can talk about idealized interests which may not be that), but this in itself is a very rare case and doesn't support this argument for antinatalism since its overwhelmed by people satisfying sincere non-hedonistic preferences to live for their family and other purposes even if somehow pain could somehow be found to be higher than pleasure in a technical sense.

Consent to Exist

This refers to the usually deontological claim that acting on another (i.e. inevitable harm of some measure) without consent is always wrong (or at least inherently results in a harm), and that because (according to them) a non-existent being can not consent to come into existence then the act of creating a sentient being is always wrong.

To be clear, the steelman version of this argument deals specifically with personhood or potential personhood, looking only at situations in which a person comes into existence at some point (from nothing, or from something that was not a person), and not with non-sentient not-potentially-sentient entities/non-entities where no person arises or is expected to arise, this is explained in more detail here. As such, this article uses the terminology of "person" and "non-person" (a non entity is a non-person, but not all non-persons are non entities; e.g. chairs, which are irrelevant to this discussion).

The consequentialist equivalent may accept certain justifications for acting upon others without consent, such as for some greater good (or avoiding a greater harm), though this is a slightly weaker and inevitably non-absolute form of antinatalism so it's not the primary focus of this section -- although the points still apply to the principle assumptions regarding the moral relevance of consent.

Provenance

The consent argument seems on its face a very bizarre argument which exists only as an ad hoc rationalization for antinatalism rather than some general moral principle from which antinatalism would be derived as its advocates suggest. That is to say, antinatalists likely start with the conclusion that antinatalism is correct and then try to come up with axioms that support it, and then try to connect those axioms to something else to lend them credibility. An argument can of course appear from nowhere and still be valid, but there's a specific kind of ad hoc argument that's particularly problematic and the intellectual dishonesty of such ad hoc axioms is discussed at more length here.

There are two potential sources apparent for the axiomatic dogma around consent.

First is the consent/anti-rape movement from which specific claims about sexual consent (in a legal sense as part of the reformed definition of rape) may have been generalized in young people to an inherent need for the same kind of explicit consent for *every* choice that may eventually have any negative effect on another person. Taking consent to an extreme like that is obviously impracticable -- to travel by car you would need consent from every pedestrian who is put at risk (other drivers arguably offer implicit consent by driving), and every person who could possibly inhale the car exhaust or particulates from the tires. To put it simply you wouldn't be able to actually do anything -- naturally anti-natalists making this argument ignore all other implications of these arguments. The claims of the anti-rape movement of course do not support this radical interpretation, nor is it consistent with the vast majority of accepted social practice or even practicable. It should also be noted that the anti-rape movement is more closely aligned with reproductive freedom. However, despite how tenuous it is, this remains the most plausible connection.

The second claimed source is much more dubious: A supposed extrapolation from dogmatic personal sovereignty as found in systems such as Randian Objectivism. As the axiom goes, violating personal sovereignty is morally wrong. This derivation, however, can be easily debunked to provide evidence against antinatalism rather than for it:

The claim is that you can't act on other persons without consent, and thus because a non-persons can't consent means you can't procreate -- but non-persons are not persons, so it's impossible to violate their sovereignty. Creating a person isn't acting on that person without consent because at the point of the creative action the person didn't exist to be acted upon -- this establishes it as a neutral action at worst.

If the antinatalist claims around absolutist consent derive authority from the dogmatic personal autonomy, then that proves only that procreation is morally benign and the antinatalist claim discredits itself by owing credit to that providence. Otherwise, the claim of derivation is false and the antinatalist consent axiom is without providence amounting to nothing more than an ad hoc hypothesis devised to rationalize antinatalism itself and nothing more.

When it comes to rule consequentialist claims around personal sovereignty being derived from the purpose of perpetuating a stable society, a more credible extrapolation is actually a moral obligation to procreate at replacement rate or higher in order to replace yourself and repay that social debt you incurred from your own parents.

Definition of Consent

First, it can be important to understand what consent is:

consent nounDefinition of consent (Entry 2 of 2)

1: compliance in or approval of what is done or proposed by another : ACQUIESCENCE[6]

This of course tells us very little. Can I approve (consent) to another person having a child? If so, then there was consent for the child being born. This would of course be a more archaic use which can consider people as property and having rights over one another in a hierarchy of dominion that stretches up to god, but isn't ultimately contraindicated by common definitions. Likewise, can I consent to something after the fact or when the action is ongoing? These definitions don't help us out much there either; they do not say approval of what *has been* done by another, but they also don't say *will be* done; the present tense can be an ongoing action. As a child of my parents can I consent to my parent's ongoing behavior of procreation? Seemingly so, and as part of that I would consent to having being born. It's both a fuzzy definition and a fuzzy concept which is one of many problems for an absolute dogma around consent (which is not to say that consent isn't important in some situations as explained later).

In practice today, consent has a range of usages both common and more technical -- of these it is typically grouped into "types" of consent from explicit/expressed informed consent of various kinds to implied consent and consenting by proxy for somebody else and every combination thereof. Every field has its own standards for consent and its own ways of categorizing them: there is no objective qualification or accounting of the "types" of consent that would make credible any claims of "there are three/four/five types of consent in the universe" because consent exists on a spectrum along various axes -- however, these axes can be understood:

1. Party

This is a question of degree of distance and authority. Who is doing the consenting? Is it the person/thing being acted upon or that will ultimately be affected, or another? What state of mind is the party doing the consenting in? Is the person his or herself whatever that means? Does it even have a sense of self or personhood? Ultimately the theoretically perfect case of this would be that the one being acted upon is a person who is the same one giving consent in a perfectly sound state of mind and with a perfect sense of self consciousness -- this is of course an impossible ideal. The impossibility of perfection here doesn't mean getting as close as possible isn't valuable, but it does doom the absolutist claims about consent and about the inability to obtain it being (in effect) intrinsically bad.

2. Information

How informed is the party who is giving consent? Again, this lies on a spectrum from complete ignorance to perfect omniscience of the act and all of its context and consequences -- the latter being again impossible. The impossibility of perfect information again doesn't invalidate the value of getting as close as we can, but again dooms absolutist claims.

3. Expression

How is the consent expressed, or is it expressed at all? The worst case here is an extremely generous "implied" consent where we just assume consent because a person has not communicated clearly enough that he or she does not consent and is not noticed to be physically opposing it, better if if that assumption is made at least on the basis that most parties do or would consent, better still is spoken consent improved by removing any possible ambiguity until we reach another (currently) impossible standard of infallible mind-reading. Yet again this impossibility doesn't invalidate the value of getting close, but yet again dooms absolutist claims.

As you can see, along every axis of variable relevant to consent there is a spectrum and an impossible perfect extreme -- perfect consent is impossible, so we're *always* dealing with various degrees of imperfect consent. Deontology fails to deal with nuance like this, preferring either-or circumstances, but that's not in line with the reality of consent in this universe. Consent is not an either-or absolute, and so it can not be an absolute standard for right and wrong behavior -- that of course doesn't mean it can't be a relative standard of more or less wrong actions depending on the degree of consent achieved, but such nuance is not something antinatalists are fond of and it's something intrinsically at odds with any strong antinatalist position.

Consent for Non-persons

The typical argument from anti-natalists goes something like this:

"A would be (not yet) person can't consent to come into the world (or inevitable harm), so having children is always wrong"

The obvious rational reply is by analogy: "Infants can't consent to medical procedures so parents consent for them, how is that different?"

This anti-natalist objection to consent by-proxy or substitution is overwhelmingly contradicted in practice with medicine: When somebody is unconscious or unable to consent to medical care (or other immediate issues) we typically rely on professionals and family to consent for them. This isn't seen as a problem, so nobody is acting inconsistently by allowing the will-be family (like the mother) to consent for the birth of her beloved soon to be child.

To deal with that problem, anti-natalists may try to draw a superficial semantic distinction about consent misunderstanding the question of moral relevance, something like:

"The infant exists (whether as a person or a potential person) and a non-person does not, in order to consent for somebody you have to be able to identify who is being consented for and a non-existent not yet person can not be identified"

There are many equally obvious problems with this reasoning aside from the most obvious as per the definition: this claim begs the question, there's no reason according to definition one would need to conclusively identify the one being consented for. But if we assume that's true, there are far more problematic aspects to the claim:

The first and most essential problem (one that makes the point irrelevant and philosophically tone-deaf) is that while anti-natalists may attempt to refute the comparison by drawing an arbitrary semantic distinction between consent for an infant and consent for a potential somebody who isn't born or conceived yet (a claim that again isn't supported by the definition), even if it were true this remains an arbitrary semantic distinction and nothing more -- it is not a *morally relevant* distinction. The anti-natalist claim completely misses the philosophical significance of substituted consent which is to act in the best interest of the person or not-yet-person when more explicit consent can't be obtained. The spirit of substituted consent is (along with all morally relevant considerations) maintained even if the principle can be argued not to apply on the basis of some kind of morally irrelevant technicality.

The second problem is the attempt of anti-natalists to have their cake and eat it too. You can not say consent for a non-person is impossible because a person can not be identified without also realizing that violating consent for a non-person is also impossible since violating consent requires a person to be identified who is being acted upon without consent. If there is no person, then technically, consent should not be an issue: when the act is actually done there is no person, so the act can not be a violation of consent and thus can not possibly be wrong as such a violation. It's much like Epicurus' witty paradox about the fear of death (indeed fear of death itself doesn't make much sense, but a want of life does):

“Why should I fear death? If I am, then death is not. If Death is, then I am not. Why should I fear that which can only exist when I do not?"

-Epicurus

The person simply can not exist when the action to create a person is initiated. Only long after the act is done does a person come into being (in fact of reality, that fetus becomes a person very gradually into childhood) -- at that point consent arguably becomes relevant to actions on or affecting that person, but never to actions on a non-person which account for all of those actions prior to the person's actual existing. IF you can credibly point to the eventual person as a victim of the action whose consent was violated, then likewise that will-be-person can be identified for substituted consent as they claim to want in the same way it may be done for an infant or other person unable to consent in medicine. Indeed, they seem to have no problem identifying the will-be person in arguments.

The third and final problem is the false dichotomy of extant vs. non-existant: outside of quantum mechanical processes that we have no deterministic control over, something does not come from nothing. Everything exists in a spectrum of change, including the actual transient and arguably somewhat subjective nature of personhood itself as hinted to earlier. Persons don't just pop into existence from nothing. Infants have little or no sense of personhood yet, so how can you identify a *person* in a vessel that does not yet have that capacity? And how can even an incomplete person be identified fully? If we identify the person the infant might become from the cloud of future possibility, how is that any more credible than identifying the person an egg might become from the same? Contrary to the antinatalist claim, there is never truly *nothing* to identify there, there's always the basic genetic information and progenitor cell line. From an egg and a pool of sperm, to a fetus, to an infant, and even to an adult who may still fundamentally change as a person into somebody else, what we're talking about is a cloud of future possibility that is only constricted over time, but never to a certainty and never from truly nothing. The very idea of such a dichotomous ability or inability to identify a person through time is not coherent.

The arguments to attempt to get around this are similar to those of anti-abortionists who want to establish an objective point of identification where they can claim moral value arises at. Is a person identified by DNA alone? Then what of identical twins and clones? What are the implications for tumors and abortions? What if the choice to bring a new person into the world pre-identified the egg and sperm used (which could conclusively ID that DNA) rather than relying on luck? Or what if that choice occurred after fertilization coming from the decision to abort or not? These are questions anti-natalists do not answer because they have no answers for them, all they can do is draw an arbitrary line without justification in attempt to prop up a dogma they have already decided was true without careful consideration.

The only clear way around these problems is to refuse to answer the question of why it's different for an infant, and just assert that it is, such as: "Brining a person into existence requires explicit consent from that person prior to bringing that person into existence, but substituted consent can be used for people who already exist and for infants to fetuses who may not be people yet"

Why? Just because they say so. Obviously this is an assertion, not an argument, and at that it is a much more transparently ad hoc assertion that makes increasingly detailed and specific claims in violation of occam's razor. Avoiding an endless trail of increasingly detailed assertions is why establishing Antinatalism#provenance is important.

The importance of personhood

An unusual rejection of these critiques by antinatalists is to contest the importance of personhood, claiming instead the issue is with existent entities or non-existent non-entities. Dealing with this claim -- the weakest argument -- would make it appear we're addressing a strawman, so the consent section overall deals with personhood as a steelman and to address the strongest form of the argument.

Any very rudimentary consideration of this personhood rejecting claim shows its absurdity: if consent is always required regardless of personhood or "potential personhood" (where a person would arise from the act in question) status, then we would need the consent of rocks to act upon them, and because they can not consent acting upon rocks (or any inanimate thing) is wrong.

The antinatalist may attempt to escape this absurdity by claiming the rock is an extant entity and thus because we can identify it we may consent on its behalf. Consenting on behalf of rocks to justify actions is already absurd, but it gets worse. The obvious reply to this is that egg and sperm are extant entities we can consent on behalf of just as much as one might on behalf of a rock, the same goes for the zygote, the fetus, etc.

To this the antinatalist might object on the grounds that something is coming into existence, so the zygote can't exist to consent for when there's is only egg and sperm. The obvious answer to that is that something is not being made from nothing, but from parts, and in this sense creation or "newness" is a subjective concept. Cutting a rock into a brick makes a brick where there was none. Making any one thing or a combination of things into something else *always* follows this pattern: Wood into a chair, mud into a pot, etc. Thus, the antinatalist would have to admit it is wrong to change the nature of any thing or things to make something "new" because that new entity doesn't exist prior to being created and can not be consented for.

This is why personhood is essential: it identifies a fundamental change from non-person substance to person-substance which can be examined. Without assenting to the essentiality of personhood in the discussion, the only honest and consistent response the antinatalist can give without abandoning the consent claim entirely is:

"Exactly! Everything we do and every inanimate thing around us we affect is morally wrong, including breathing air and changing it into CO2 because the CO2 can not consent to exist before it exists and we can't consent for it because it's a non-existent non-entity! That's why all existence must be ended!"

This does not disprove the claim in itself, but it would amount to an extremely successful reductio ad absurdum (showing an asserted claim is so absurd a person would have to be insane to believe it).

Gambling Thief Analogy

In response to the claim that most people end up being reasonably happy about existing, commonly an analogy to stealing somebody's money and gambling with it (giving them the proceeds) is made, however this analogy fails in many important ways.

Most crucially, gambling is monetarily Zero Sum at best with a game among friends (some make off better and some make off worse, but on average there can never be a profit because money doesn't come from thin air during the game), and worse gambling is even negative sum for players when there is a casino involved (because while some win some lose, the house always wins and on average players always lose money) -- this is not the case with life.

Unlike with money in gambling which has a fixed sum, there is no cosmic law of conservation of happiness with life that guarantees there must be losses for every gain; two people can make each other happier without taking it from each other or from others (neither is there conservation of misery). Life is what we make it and can be zero sum, negative sum, or positive sum depending on how we live it as a society (or any arbitrary group you're introducing a person into); thus the analogy to gambling is fallacious because the average odds are not guaranteed to be neutral to negative for people in any given country or even all people alive today -- it just depends on empirical matters such as the situations we're born into (e.g. what country/socioeconomic status are we talking about) and what we do (do we help each other, or are we in perpetual warfare?). Depending on the empirical facts it could easily be wrong to have children in some time or place where the odds are bad and life is negative sum and right to have children in another time and place where the odds are good and life is positive sum -- as explained originally, this is not antinatalism in the broad sense.

If you stole money from people to gamble, on average you would never be able to give them back more than you stole; this is statistically a harm, thus it's wrong to do because you will cause more harm than benefit. If you had a magic slot machine that broke the laws of gambling by creating money from nothing and paid out so substantially more than you put in, where losses were incredibly rare, and the overwhelming majority of people you stole from to play the game for them were thankful for it, that would be very different. It would depend on the slot machine you were using and the empirical facts of its average payout -- which in life like the magic slot machine is not fixed at negative sum as they are in a real world casino.

If for some reason you were unable to ask consent to borrow a quarter from your friend's wallet to use in that magic slot machine which closes in one minute for a 99% chance of winning big for him on his behalf (something he or she would almost certainly consent to if it were possible), it would arguably be more ethical to take the risk on his or her behalf in order to yield a much greater benefit.

It's hard to imagine a realistically analogous scenario for a living person so pressing and odds so favorable that we'd be unable to ask for consent, so most of the time we're dealing with the *choice* not to ask for consent when it could be asked for -- that's another issue covered below. In the case of procreation, though, at least for a happy privileged human family who are glad to exist (that is introducing a person into a situation with good odds because it's a positive sum societal group they're entering), we're dealing with a magic slot machine that almost always pays out more than it takes that parents may choose to play on behalf of a not-yet-born person and the gambling thief analogy does nothing to contradict the positive moral value for them of doing so.

When we look at specific socioeconomic groups that give children born into them great odds we can also talk about the possibility of a global negative sum if those groups are depressing others (so possibly causing more global harm) which introduces the complexity of it being the *right* thing to do for that child but the *wrong* thing to do for the world, however this is beyond the scope of the gambling thief analogy and represents another empirical question that antinatalists have not provided good evidence for (for instance, in economic terms it appears wealthy nations benefit other countries through trade, and there's again no evidence of a general zero-sum game between nations but rather a mutual benefit more on that here). Unsustainable practices like those that contribute to Global warming are something different (ultimately lose-lose for everybody), that's discussed more here.

Acting Without Consent

Even understanding that perfect consent is impossible, a broader challenge worth mentioning is the dogma that acting without consent (in any degree) is always wrong. The problems deontology has with consent have already been covered, but why might consent be important at all in a consequentialist framework?

In practice it is usually inappropriate to do things to others (or that significantly affect others) without their consent when they're capable of giving it even if you think it'll be OK, but the reasons for this are complicated and have more to do with ulterior motives that gambit would imply and the reflection on *character* rather than any certain material harm.

Because consent is usually a very reliable way to determine if something is in another's interests or not, if it's easy to ask it eliminates the possibility of acting against those interests. Even if you're 99% sure somebody wants something, you don't have to take the risk they don't if you have the ability to ask. Therefore, if it's possible to ask we should, and that's what makes not asking (where possible and practicable) wrong. It's creating an unnecessary risk. This is not true where asking consent is impractical or impossible: the impracticality or impossibility of the query can justify the small risk of violating interests (or would-be interests of the future person in the case of procreation).

To be clear it's not the acting without consent in situations where it would be easy to obtain consent that is necessarily wrong in itself, it's the failure to ask consent when it's easy to do so that was wrong -- at least in terms of how it reflects on character. To bring this back to the implied gambit, if you ask first, whether the consent is given or not you are acting in the interest of the person so there is no harm (to that person) from asking. If you do not ask, you may be acting against the interests of that person, so likely the only motivation for not asking is selfish (that you WANT to do the action and don't want the risk of a "no" which would force you to stop or remove the plausible deniability that you were acting against the person's will).

Such is the case for sexual intercourse: the only reason somebody would not get consent is if he or she wants to do it regardless of consent. Consent is not asked because the aspiring rapist doesn't want the risk of confronting a no and either having to stop or having to actually admit to himself that he's doing a rape with no plausible way to deny it. There's an inherently selfish motive there which indicates a willingness to do harm for one's own benefit. It's almost always possible to ask for consent at some point, and sexual intercourse is almost never so urgent as require it go ahead without being able to ask -- thus the whole fixation on consent as the ultimately litmus for not being a rapist regardless of what you assume the person wants.

Of course, there are grey areas and exceptions to every rule. A woman whose husband had an accident and went into a coma from which he won't awaken, but whose sexual organs are still functioning, may wish to have a child with him knowing he wanted that too and trying to keep a part of him alive. He's no longer a person in any meaningful way, there's no way to ask for consent, or to wait for it, and yet it was understood that this is something he wanted. He might have changed his mind knowing he wouldn't be around to see them, but there's no way to know that. Is it wrong? Is it rape?

The bottom line is that there's nothing innate to consent, but rather the kind of motivations behind not asking when it's possible and the benefit consent has in increasing the probability that we're respecting somebody's interests. When it's not possible to ask consent and the probability is high that our actions are in line with the person's interests (or the would be person's likely future interests) then the argument that consent hasn't been given is morally irrelevant.

So because consent can not be asked of the will be child, the failure to do the impossible does not reflect negatively on character and is not wrong as long as we're doing our best to act in accordance with the interests the will be child will probably have in the future. The only genuinely important philosophical question around bringing children into the world is whether it does more good or more harm, and that's an empirical one that has nothing innately to do with consent.

Negative Utilitarianism

Beyond flagrantly absurd arguments like Benatar's asymmetry or unfalisifiable empirical claims of existence bias, and beyond very questionable arguments about consent, there's a much more complicated and philosophically substantial underlying issue of Negative Utilitarianism or Negative Consequentialism (different but for these purposes well just cover Utilitariansim since it's the typical example).

Under negative utilitarianism, suffering is bad, but pleasure is not good -- there is a natural asymmetry in the premise. Following from that premise, general philosophical antinatalism and efilism is a valid deductive conclusion; that is, barring any confounding variables in specific cases (like having a child who will cure cancer and reduce suffering more than that child causes or experiences it). Negative utilitarianism leads to the most solid antinatalist position a consequentialist can take.

Keep in mind, the philosophical position of antinatalism indicated here should not be confused with promotion of antinatalism to the general public (see being vs. promoting above).

While most people will find negative utilitarianism intuitively unappealing (effectively, there is only bad and no good), negative utilitarians make some compelling arguments of philosophical interest and that may appeal to certain intuitions in the right frame. Negative Utilitarianism is far too involved to cover fully in this article, and it's also relevant to other topics, so please see the main page on Negative Utilitarianism, for in depth discussion on the advantages and disadvantages of the axioms of those systems, and the implications.

Most of the rest of the arguments and issues discussed following on this page also apply to negative utilitarians, so the truth or falsehood of those axioms are not essential to more extensive discussion on the practical matters of antinatalism and the relative harms of life.

Extreme Ends

While much of antinatalism focuses on rights and contemporary suffering of each individual born, or those they affect through environment etc. without any end goal, a significant voice in anti-natalism is a consequentialist aim of human extinction (voluntary or not) or outright extinction of all sentient life. These ends based approaches have much more serious logistical problems that are either unaddressed or addressed with weak speculative science.

Human Extinction

Where other arguments are more focused on the suffering of humans who come into existence, or their right not to, arguments for human extinction may be promoted with or without those assumptions.

The core of the human extinction argument is a misanthropy that claims humans are an evil in the world, and it would be better for the world if we didn't exist -- in particular, that it would be better for the other sentient beings in the world with whom we do a poor job sharing the Earth and whom we treat poorly.

Not only are such arguments speciesist against humans, they're usually based on a romanticized idea of nature and ignore the reality of Wild Animal Suffering, or worse claim that the suffering of wild animals is unimportant and that only the natural aesthetic is important. Aesthetic arguments are hard to tackle, being subjective assertions of good based on personal taste, but those based on suffering that humans cause are simple to tackle: While it's clear that a world where humans are kinder to other beings and each other is better, it's unclear if a world without humans would actually be better. Human extinction would just open a new ecological niche which would likely be filled in a few million years (humans evolved in a blink of the eye in geological time). Hitting the reset button is not guaranteed to have a better outcome: what comes after us may be just as cruel or even more cruel than humans have ever been.

Denying this argument hinges either on denial of evolution, or an insistence that humans are uniquely cruel and that another primate that evolved to take our place (or masupial, or feline, etc.) would be kinder even if it evolves to fill essentially the same niche humans did -- a claim likely rooted in speciesism and irrational optimism about the natural world.

Because we have the potential to become better (as has been the trend in societal progress), it's better to keep trying with the possibility of improvement rather than resetting everything to zero and starting over when there's no evidence of better odds for the next go-around. The odds may even be worse the next time, because the next species may lack the readily accessible resources that humans have already exploited, limiting its technological and social development -- that means this may be the only chance Earth has for possibly hundreds of millions of years to develop conscientious caretakers. There's no reason to believe humans are uniquely bad or that the worst of it will last indefinitely.

As an extension to the Human Extinction argument, based on wild animal suffering and the potential for another human-like being to just evolve in our place, some argue for the involuntary eradication of all life on the planet (or even all life in the universe). See Efilism.

Efilism

Efilism, the ideology that all sentient life is bad. It's distinct from antinatalism in that not all antinatalists are efilists, but linked to it because Efilists are a kind of antinatalist. Efilism is often argued (and argued well) to be the only logical conclusion of most antinatalist philosophy due to the failure of voluntary antinatalism (see dysgenics), and the significance of suffering of other life forms that can't consent to annihilation or abstain from reproduction willingly.

There will likely always be a fringe ideology that believes life is inherently bad and wants to forcefully wipe out all sentient life on the planet or even in the entire universe. You may even agree with that position in a philosophical sense. However, it must be understood that these systems are in the eyes of modern people tantamount to comic book supervillain motivations.

Its inherent unpopularity, at least today, is why like a comic book supervillain any attempt to put it into practice is likely to fail and only cause a large amount of suffering in the attempt. Efilists are not out merely to cause more suffering, so must consider that the most likely result of an attempt (like releasing a virus) of merely killing a few people and maiming or sickening millions without successfully wiping out the population only makes things worse. The fundamental obstacle to Efilism is that it's a non-starter even if it were true in principle (which is discussed in other sections of this article). Here we'll skip over the philosophical objections -- many, varied, and already covered in other sections -- and touch on the impracticability of the thing.