Difference between revisions of "Antinatalism"

(→Benatar's Asymmetry) |

(→Quantitative Benatar's Asymmetry) |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

==Quantitative Benatar's Asymmetry== | ==Quantitative Benatar's Asymmetry== | ||

| − | A serious problem is that despite Benatar recognizing the fact that these things can be quantified and weighed (he recognizes a life can be net bad even if there's some good in it), he is unwilling to engage in quantitative analysis of the goods and bads in life vs. unlife. This makes his claims inherently inconsistent, and probably also intellectually dishonest when he uses arguments that are inconsistent with his | + | A serious problem is that despite Benatar recognizing the fact that these things can be quantified and weighed (he recognizes a life can be net bad even if there's some good in it), he is unwilling to engage in quantitative analysis of the goods and bads in life vs. unlife. This makes his claims inherently inconsistent, and probably also intellectually dishonest when he uses arguments that are inconsistent with his own when it suits him. |

If we examine quantity of good or bad, the effect is that the asymmetry argument engages in double counting for pain without justification, but that it isn't impossible for life to be better than non-life. | If we examine quantity of good or bad, the effect is that the asymmetry argument engages in double counting for pain without justification, but that it isn't impossible for life to be better than non-life. | ||

Revision as of 22:58, 28 May 2018

Anti-Natalism is the general or universal belief that there is negative value to procreation.

While there are usually specific cases where sensible people are anti-natalist in a limited sense, like during wars, that in itself is not anti-natalist in the broad sense (which this article discusses). Likewise, vegans usually promote limited anti-natalist positions with respect to farmed animals and believe breeding these animals for a life of suffering and an early death is wrong, again that is in itself not anti-natalism.

Anti-natalists do not have objections merely to specific cases of procreation where inordinate harm is involved, but to procreation generally even from healthy, secure, well adjusted parents; and even to socially and environmentally conscious parents who would pass those values onto their children.

The claim, as many broad claims are, is typically deontological (or dogmatic) in nature and not founded on consequentialistic reasoning that considers exceptions. There are consequentialist anti-natalists, but usually of a special negative variety (based on blind adherence to claims like Benatar's Asymmetry).

Contents

Benatar's Asymmetry

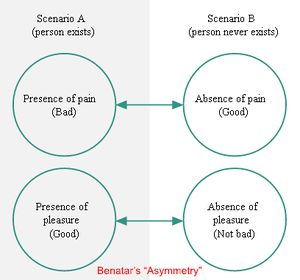

One of the Bad Arguments for Veganism Benatar's asymmetry claims on intuition that the absence of pain is good, but the absence of pleasure is not bad.This is related to negative utilitarianism, which bases assessment only on pain and ignores pleasure entirely. The apparent distinction is that Benatar doesn't deny the positive value of pleasure during existence as negative utilitarians do, but this may be a meaningless distinction if you only look at qualitative (all or nothing style) analysis (as he seems to prefer):

My view is not merely that the odds favour a negative outcome, but that a negative outcome is guaranteed. The analogy I use is a procreational Russian Roulette in which all the chambers of the gun contain a live bullet. The basis for this claim is an important asymmetry between benefits and harms. The absence of harms is good even if there is nobody to enjoy that absence. However, the absence of a benefit is only bad if there is somebody who is deprived of that benefit. The upshot of this is that coming into existence has no advantages over never coming into existence, whereas never coming into existence has advantages over coming into existence. Thus so long as a life contains some harm, coming into existence is a net harm. -David Benatar[1]

That is, the absence of life is always qualitatively "good" to Benatar, but the presence of life may be "good" or "bad" depending on how much pleasure or pain there is. The way he achieves this dichotomous result is through all or nothing yes/no good/bad style analysis with no concept of gradation.

Consider Bob, who has a wonderful life filled with happiness and pleasure, but he gets a paper cut once. The happy life merely counts as "pleasure" which is good, and the paper cut counts as "pain" which is bad.

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| Pleasure | Good | Neutral |

| Pain | Bad | Good |

| Total | Neutral (good+bad) | Good |

Because you fail to consider the magnitude of good and bad, and only look at a dichotomous result, all lives must inevitably be bad.

Quantitative Benatar's Asymmetry

A serious problem is that despite Benatar recognizing the fact that these things can be quantified and weighed (he recognizes a life can be net bad even if there's some good in it), he is unwilling to engage in quantitative analysis of the goods and bads in life vs. unlife. This makes his claims inherently inconsistent, and probably also intellectually dishonest when he uses arguments that are inconsistent with his own when it suits him.

If we examine quantity of good or bad, the effect is that the asymmetry argument engages in double counting for pain without justification, but that it isn't impossible for life to be better than non-life.

As an example, consider the existence or non-existence of Bob, who has a life with 5 units each of pleasure and pain (presuming we have a good method to measure it):

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 units Pleasure | 5 | 0 |

| 5 units of Pain | -5 | 5 |

| Total | 0 (neutral life) | 5 (good non-existence) |

Here Benatar's asymmetry says that it's better than Bob not exist than exist.

Even with a comparatively good life, this is the case:

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 6 units Pleasure | 6 | 0 |

| 4 units of Pain | -4 | 4 |

| Total | 2 (Good life) | 4 (Better non-existence) |

Benatar's asymmetry would even claim that people with good lives, including significantly more pleasure than pain, would be better off not existing, which is a very serious violation of intuition, but at least follows from his premised.

Where he contradicts himself is that this is not always the case in a comparative assessment. In order to even break even in quantitative analysis, a life would have to contain twice as much pleasure as pain. However, contrary to Benatar's claims, if a life is sufficiently happy, it obviously IS better than non-life despite the unjustified double counting of pain.

| Existence | Non-Existence | |

|---|---|---|

| 10 units Pleasure | 10 | 0 |

| 2 units of Pain | -2 | 2 |

| Total | 8 (Very Good life) | 2 (Slightly good non-existence) |

Here existence is clearly preferred (offering more good) than non-existence. So if Bob lives a great life of happiness and contentment and get a paper-cut once, it IS better that he had lived than not. Benatar is simply wrong that it is guaranteed that life will always be less than non-life, leaving the question of whether we should or should not have children up to empirical contention. It is very likely that a significant number of humans and non-human animals live lives they would consider at least twice as happy and pleasurable as they are sad, and so if used consistently, an honest interpretation of Benatar's asymmetry does not result in broad antinatalism.

The only way Benatar's asymmetry comes to the certain conclusions he wants (that life is always guaranteed to be bad vs. non-life) is to engage in not one, but two forms of unjustified manipulation: Double counting pain AND assessing the results only qualitatively (yes or no) rather than quantitatively (a spectrum).

Asymmetry as an Assertion

There are many practical problems with the argument, but most substantial is that they're based merely on assertions of which the opposite can be just as credibly claimed. The opposite assertion is: the absence of pleasure is bad but the absence of pain is not good.

This inversion would cause even a life of net suffering (as in animal agriculture) to possibly be better than no life at all. In the case of dismissing quantitative analysis, then even the worst factory farming would always be moral if the animal inevitably experienced some kind of small pleasure at some point in life.

And because Benatar's asymmetry is based on no reason whatsoever, there's no reasonable argument a proponent can make against somebody claiming the precise opposite, promoting the most cruel factory farms, or even procreation in cases of overpopulation in less developed countries that do result in substantial human suffering.

When you throw out the idea that amount of pleasure and pain matters, you can promote any kind of position based on ad hoc assertions of asymmetry, and these assertions can be just as easily turned on their heads to advocate the precise opposite view.

Existence Bias

An unfalsifiable but seemingly empirical claim that we are biased about our own existence, so we're perpetually in error when we assess that we enjoy life/that we are generall happy about having been born, and instead are in fact subject to far more bad than good in life.

It's a serious problem to make controversial and forceful prescriptions for others based on unsubstantiated (and particularly unfalsifiable) claims about empirical reality. To demonstrate why this is, the very opposite can be just as easily asserted, or even apparently absurd (but still unfalsifiable) claims about factory farmed animals experiencing more pleasure than pain despite appearances: a carnist may just as well claim that the farmed animals are just stressed because they have "pessimism biases" but in fact are experiencing far more goods than bads and so the industry is moral. Assertions like this are not productive to discourse. However, the principle of why this kind of unfalsifiable claim is categorically problematic is difficult to explain to anti-natalists.

Fortunately the force of this claim, if true, also depends on on a hedonistic value system (as opposed to a preference system) where pleasures and pains can be objectively weighed against each other to come to a conclusion as to whether your life has net negative or positive value to you regardless of how you actually feel about it or what your interests are -- and this is a claim that can be attacked very persuasively for most people using simple thought experiments that challenge intuitions on this point (The "pleasure pill" challenge that puts a person in a mindless euphoric coma to maximize hedonic pleasure), as well as challenged philosophically on its arbitrarity (why is this particular electrochemical signal bad? Why is another good? What about species with different neural architecture?), and empirically based on its connections to psychological egoism. Challenges to hedonism can be found in more detail in Hedonism vs Preference.

Within a preference framework, such claims of Existence Bias don't make any sense unless you're talking to somebody who claims to only prefer maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain (in which case you can talk about idealized interests), but this in itself is a very rare case and doesn't support this argument for antinatalism since its overwhelmed by people satisfying sincere non-hedonistic preferences.

Consent to Exist

The deontological claim that acting on another without consent is always wrong, and that because a non-existent being can not consent to come into existence creating a sentient being is always wrong.

In response to the claim that most people end up being reasonably happy about existing, commonly an analogy to stealing somebody's money and gambling with it (giving them the proceeds) is made, however this analogy fails in many important ways.

Most crucially, gambling is Zero Sum, often even negative sum (because the house always wins) and life is not. If you stole money from people to gamble, on average you would never be able to give them back more than you stole; this is statistically a harm, thus it's wrong to do because you will cause more harm than benefit. If you had a magic slot machine that paid out so substantially more than you put in, losses were incredibly rare, and the overwhelming majority of people you stole from to play the game for them were thankful for it, that would be very different.

There's also a huge difference with respect to the potential to obtain consent: When somebody is unconscious or unable to consent to medical care (or other immediate issues) we typically rely on professionals and family to consent for them. The people you are stealing from to gamble for presumably would be capable of consenting or declining your proposition if you asked them. It's typically inappropriate to do things without people's consent when they're capable of giving it, but not when they aren't, so this analogy of stealing from people to gamble for them is a poor analogy to the pre-birth state; you would have had the option to simply ask them and find out for sure if they were OK with it or not.

If it were the case that you had a magic slot machine that paid out BIG 99% of the time, but you only had access to it today, had no money, and your friend was in a convenient coma for the day with his coin purse beside him, YES you should take a quarter and play the slots for him, because he probably would have wanted you to do it.

Human Extinction

Where other arguments are more focused on the suffering of humans who come into existence, or their right not to, arguments for human extinction may be promoted with or without those assumptions.

The core of the human extinction argument is a misanthropy that claims humans are an evil in the world, and it would be better for the world if we didn't exist.

Such arguments usually ignore the reality of Wild Animal Suffering. While it's clear that a world where humans are kinder to other beings and each other is better, it's unclear if a world without humans would actually be better. Likewise, human extinction would just open a new ecological niche which would likely be filled in a few million years (humans evolved in a blink of the eye in geological time). Hitting the reset button is not guaranteed to have a better outcome: what comes after us may be just as cruel or even more cruel than humans have ever been. Because we have the potential to become better (as has been the trend in societal progress), it's better to keep trying rather than resetting everything to zero and starting over: and this is particularly true because the next species may lack the readily accessible resources that humans have already exploited, limiting its technological and social development, meaning this may be the only chance Earth has to develop conscientious caretakers.

As an extension to the Human Extinction argument, based on wild animal suffering and the potential for another human-like being to just evolve in our place, some argue for the involuntary eradication of all life on the planet (or even all life in the universe). These people take themselves very seriously, but they're essentially cartoon super-villains.