Defunct NameTheTrait V1

Note: This article is a work in progress

To jump to the proof of logical invalidity see Proving NTT Fails as a Formal Argument

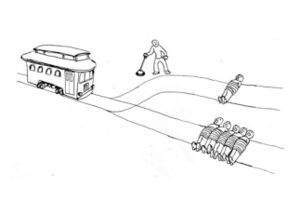

Name The Trait, or #NameTheTrait is a logically invalid (non sequitur) argument for veganism formulated by vegan Youtuber Ask Yourself in 2015, and popularized during a series of Youtube debates in 2017 by Ask Yourself and Vegan Gains a vegan bodybuilder and Youtuber. Loosely speaking, NTT seeks to establish veganism from a personal belief in human moral value, similar to the well known argument from marginal cases (or Less Able Humans). In practice, NTT is combined with extraordinary claims such as, ' animal rights follow logically from human rights ', which are defended with the use of circular references and invalid generalizations.

The formal, premise-conclusion presentation of #NameTheTrait is as follows:

Argument for animal moral value:

P1 - Humans are of moral value

P2 - There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to deem ourselves valueless.

C - Therefore without establishing the absence of such a trait in animals, we contradict ourselves by deeming animals valueless

Argument for veganism from animal moral value:

P1 - Animals are of moral value.

P2 - There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to consider anything short of non-exploitation to be an adequate expression of respect for human moral value.

C - Therefore without establishing the absence of such a trait in animals, we contradict ourselves by considering anything short of non-exploitation(veganism) to be an adequate expression of respect for animal moral value.

This article discusses the three primary issues with NTT. Firstly, it discusses its logical invalidity, with a focus on the invalidity of the first, "for animal moral value" argument. Secondly, it discusses problems with the justifications used by Ask Yourself to defend the validity of the argument. And thirdly, the article discusses various problems with the second, less widely discussed "for veganism from animal moral value" argument, which yields a deontological commitment to non-exploitation.

[Please put large comments on the talk page]

Contents

- 1 Proving NTT is Invalid

- 1.1 Importance of logical validity

- 1.2 Logical Validity

- 1.3 Summary of Issues

- 1.4 Steel-Manning and Interpreting NTT

- 1.5 Proof of Failure in First Order Logic

- 1.5.1 Logical Connectives

- 1.5.2 NTT Part 1 Translation to FOL

- 1.5.3 P2 is vacuously true if "us/ourselves" represents humans

- 1.5.4 P2 is vacuously true if humans are considered to be in the set of animals

- 1.5.5 Separating humans and nonhuman animals

- 1.5.6 Showing the argument is a non sequitur

- 1.5.7 Showing NTT fails for disjoint sets in general

- 1.6 Subsequent Verbal Versions of NTT

- 1.7 Failure to engage with formal logic

- 2 Itemized Issues Discussion

- 3 Correction

- 4 Conclusion

Proving NTT is Invalid

Importance of logical validity

The main reason it helps to know whether an argument is logically valid is that it helps us to clarify if we have identified all of the substantive assumptions behind its conclusion. If we can see that an argument is valid, then we know that its conclusion follows from its premises simply because of their form, so we have identified and listed all of its substantive assumptions in its premises. If we can see that an argument is invalid, this helps us to know that it must be making further assumptions in order to be a good, rationally compelling argument. Knowing that an argument is making such assumptions, and determining what they are, can help us to understand why certain individuals may not find it compelling, and can spare us the confusion of failing to understand this. It can also put us in a better position to defend those assumptions forthrightly to those who might be inclined to challenge or fail initially to accept them.

As we will see below, NTT is invalid. Seeing why it is helps us to see how certain very plausible substantive assumptions can be added to its premises to make it valid. The making of these tacit assumptions by the presenter of NTT and the audience very likely explains why it is often a compelling argument. But as we will see below, the failure to acknowledge these assumptions can cause confusion, and inhibit a persuasive defense of its premises. As we will also see, the fact that to be compelling the argument must make such assumptions may help to dash certain hopes about the minimality of the argument’s assumptions (e.g. about the nature of value and ethics). Seeing that NTT is invalid will thus help us to appreciate the argument’s limits, and how other approaches may be helpful in defending the substantive ethical views that stand behind arguments like NTT.

Logical Validity

What it is for arguments to be logically valid and invalid is the following:

- Valid: No possible case has the premises all true and the conclusion false, due simply to the structure of the premises and the conclusion

- Invalid: Some possible case has the premises all true and the conclusion false, due simply to the structure of the premises and the conclusion

In other words, for an argument to be logically valid is for the truth of its conclusion to be guaranteed by the truth of its premises due to their logical form. For instance, an argument of the form

- (P1) If consuming animal products causes unnecessary suffering, then we should not consume animal products,

- (P2) Consuming animal products causes unnecessary suffering,

- Therefore, (C) we should not consume animal products

is logically valid. This is because it has the logical form:

- (P1) If U then V

- (P2) U

- Therefore (C) V

Here, C follows from P1 and P2 simply due to their logical form, whatever the content of U and V may be (this particular way of a conclusion following from its logical form and that of the premises is known as "modus ponens").

Thus if we can show a case where the logical form of the premises and conclusion of NTT allow the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false, we will have shown that the argument is invalid. Such a case is referred to as a counterexample.

To see how to formally prove an argument is valid see Proving Formal Arguments (still a WIP).

Summary of Issues

For reference, Part 1 of NTT is as follows

- P1 - Humans are of moral value

- P2 - There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to deem ourselves valueless.

- C - Therefore without establishing the absence of such a trait in animals, we contradict ourselves by deeming animals valueless

The primary issues that are established with the argument can be summarised as follows:

- P2 requires a trait that can be absent in humans

- Traits that can be absent in humans are all traits except 'being human' and 'moral value' (moral value because of P1)

- Traits that could give moral value to animals based on P1 are 'being human' or 'moral value'

- Neither of these traits can satisfy P2 as they cannot be absent in humans

- Therefore P2 does not assign the traits 'moral value' or 'being human' to animals

- Hence C 'Animals have moral' does not follow from the premises and the argument is a non sequitur

- If 'us/ourselves' in P2 refers to humans, then P2 becomes irrelevant since P1 says humans can never be valueless

- Even if NTT did establish that there is no moral value giving trait absent in all animals that would only imply there is at least one animal with the moral value giving trait, not that all animals have the moral value giving trait (which is the conclusion)

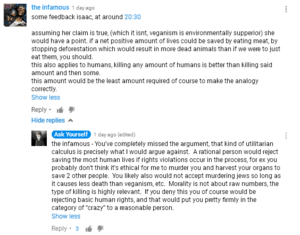

Isaac's response to these criticisms can be seen in the image to the right.

Regarding the defense, paraphrasing, ' P1 - Humans are of moral value, is a general statement ', general statements do not work in formal arguments. The statements '(1) humans are of moral value ' and '(2) some human(s) are of moral value' may seem very similar. But in formal logic, they are very different, and the difference dramatically changes what can be derived from them. With definitions used in the section below, the first statement would be expressed as

- (1) '∀x: H(x) ⇒ M(x) ' (for all x, if x is human then x has moral value)

and the second

- (2) '∃x: H(x) ∧ M(x)' (there exists an x that is human and has moral value)

This is why it's important to recognise the value of formal logic, and the necessity that we must prove the validity of our arguments with formal logic. Rigour is very important in philosophy, an argument shouldn't be able to be 'nitpicked', and formal logic is how we establish that our arguments are logically valid.

Steel-Manning and Interpreting NTT

Regarding the written version

The NTT argument contains ambiguous language such as the use of ' would cause us to deem ourselves valueless. ' in P2, with no clear meaning as to what is and is not ' us '. In this section we will consider the possible interpretations of such statements and demonstrate how each fail, and explain the interpretation we will use for the debunk in first order logic.

To illustrate our points, in this section we will use an analogous situation wherein we substitute ' humans are of moral value ' for ' I am of moral value ' and demonstrate how NTT would fail to establish moral value in a cow which we will call Bessie (who is not you). This is motivated by some of the analogies Isaac has given in attempts to demonstrate how P1 & P2 lead to the conclusion, and because it avoids some of the issues associated with quantifying over all humans and all animals, who each have a variety of traits. Here we will take P1 to be ' P1 - I am of moral value ' and C to be ' C - Bessie is of moral value ' , and look at possible interpretations of P2 and show how they fail to lead to the conclusion.

Suppose we were to take

- P2 - There is no trait absent in Bessie which if absent in me would cause me to deem myself valueless.

This simply makes P2 vacuously true, since P1 says I can never be valueless, hence there can be no trait that could cause me to be valueless. Making P2 irrelevant, and the argument a non-sequitur. There is also another issue here, and that is that there is a difference between a trait that if absent in me would cause me to deem myself valueless , and a trait that if absent in me would cause me to actually be valueless . The distinction is that the former is a matter of perspective and the latter is a is a statement of fact, just because you have considered something as such does not necessarily make something so, and even if it did, failing to deem something morally valueless does not even mean it has been deemed to have moral value. If we allow the use of deem, we have; P1 is an assertion of fact, P2 of perspective, P3 of fact. So for the remaining interpretations we will omit the use of deem.

To avoid the issue of P2 becoming vacuously true, we will introduce the notion of a clone. Such that P2 is stated as

- P2 - There is no trait absent in Bessie and present in me, which if absent in a clone of me would cause the clone to be valueless.

This is essentially the form we will be using for the debunk in first order logic, the notion of the clone solves the issue associated with P1, since now there is nothing to say the clone can never be valueless. We are simply assessing whether or not the clone, with the trait removed, has moral value. This is a fairly reasonably steel-man that doesn't stray too far from the written argument. The reason this fails is because we can simply say the clone has moral value, and this will imply nothing about whether or not Bessie has moral value. This is because they are two different individuals, so we can simply have completely different moral standards them.

Note: if the trait 'being Bessie' is absent in you, then removing a trait, cannot cause the clone to become Bessie, see 'Showing NTT fails for disjoint sets in general'

To see why subsequent verbal versions presented by Ask Yourself fail see Subsequent Verbal Versions of NTT

Proof of Failure in First Order Logic

The use of propositional logic is motivated by the fact that the English language (or any other spoken language) contains inconsistency and ambiguous propositions. The use of predicate logic is motivated by the fact that propositional logic is not capable of using quantifiers (for all, there exists etc.). So to translate the argument in a formal way, we decided to use first order logic. It is crucial in any form of argument to be able to translate it in a formal way.

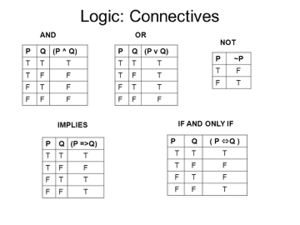

Logical Connectives

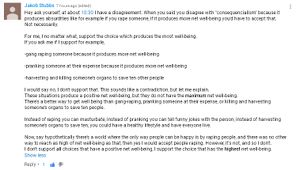

It may be helpful to understand the following basics of logical connectives and propositional logic, before reading the following sections.

In propositional logic simple statements (referred to as propositional atoms) are assigned letters such as P or Q etc., and complex statements are formed by connecting these statements with logical connectives (as seen in the picture to the right). As an example

- P = I live in Paris

- Q = I live in Quebec

- N = I am Napoleon

- (P ∧ ¬Q) = I live in Paris and I don't live in Quebec

- (N ⇒ (P ∧ ¬Q)) = If I am Napoleon then I live in Paris and not Quebec

Now using the truth tables of the logical connectives we can determine whether a statement is true or false. If we consider the previous example, we can evaluate the truth of the statement a number of cases.

(1) In the case that you are not Napoleon, and you live in New York.

- P is false, Q is false, ¬Q is true, and N is false, so

- (P ∧ ¬Q) is false (false and true gives false)

- (N ⇒ (P ∧ ¬Q)) is true (false implies false gives true)

So the statement 'if I am Napoleon then I live in Paris and not Quebec' is true, in this case

(2) In the case that you are Napoleon, and you live in Quebec

- P is false, Q is true, ¬Q is false, and N is true, so

- (P ∧ ¬Q) is false (false and false gives false)

- (N ⇒ (P ∧ ¬Q)) is false (true implies false gives false)

So the statement 'if I am Napoleon then I live in Paris and not Quebec' is false, in this case

In the following section we translate NTT into first order logic (which is more complicated than propositional logic), then construct counterexamples and evaluate the truth of the premises and conclusion, in a similar manner to above. Showing in fact that there are cases where P1 and P2 of the NTT argument are true and the conclusion is false

NTT Part 1 Translation to FOL

Symbols

- ∀ (for all)

- ⇒ (implies i.e. 'if, then')

- ¬ (negation i.e. not)

- ∃ (there exists)

- ∈ (element of)

- ∉ (not an element of)

- ∧ (and)

- \ (without)

- { , } (set of)

- :⇔ (defined as)

Definitions

- H(x) is true ⇔ x is a human being

- A(x) is true ⇔ x is an animal

- M(x) is true ⇔ x has moral value

- T(x):⇔ The set of traits belonging to x

Translation

- P1:⇔ ∀x: H(x) ⇒ M(x)

- P2:⇔ ¬ ( ∃t: ( ∀x: A(x) ⇒ t ∉ T(x) ) ∧ ( ∀y: H(y) ⇒ ( t ∈ T(y) ∧ ( ∀q: ( T(q) = T(y) \ { t } ) ⇒ ¬ M(q) ) )

- C:⇔ ∀x: A(x) ⇒ M(x)

In English

- P1: for all x, if x is human then x has moral value

- P2: There is no trait absent in animals and present in humans that if absent in a replica of a human without the trait, would make the replica valueless

- C: For all x, if x is an animal then x has moral value

The above formalization deals with two issues regarding the use of "us/ourselves" (See existential meaning).

- If we consider the product of the human without the trait to be a human, then P2 is rendered vacuously true (see proof below). This is due to the fact that P1 implies a human can never be valueless, so that in P2 there can never be a trait that if absent in humans would cause humans to be valueless.

- Thus to steel-man P2, we must consider the being that remains after removing the trait to no longer be human. When Isaac uses hypothetical situations (such as what if your brain is transferred to a computer, would it be ok to kill you? etc. ), we are no longer talking about a human anymore. So we can just admit that "us" is the product of whatever is left after removing the trait.

It's worth noting that there is nothing in the argument that forbids applying completely different moral standards to the set of humans than to the set of (nonhuman) animals. And this is the essence of why NTT fails as a formal argument, and requires additional moral universalist premises in order to be logically valid.

Note : It is up to Isaac or any other supporter of the argument to demonstrate that C follows from the premises or that the negation of C leads to a contradiction. Additionally it is also preferable to have the deduction system clearly specified. Until this has been demonstrated, the argument should not be taken as valid.

P2 is vacuously true if "us/ourselves" represents humans

In the above translation we are steel-manning P2 of the original argument by not requiring 'us/ourselves' to be human. Since P2 becomes vacuously true if the 'us/ourselves' represents humans (see below).

P2 would have the following form if "us" represents humans :

P2:⇔ ¬ ( ∃t: ( ∀x: A(x) ⇒ t ∉ T(x) ) ∧ ( ∀y: H(y) ⇒ ( t ∈ T(y) ∧ ( ∀q: ( T(q) = T(y) \ { t } ) ∧ H(q) ⇒ ¬ M(q) ) )

Note the addition of "∧H(q)" in the last part of the sentence. The sentence has the form ¬(A ∧ (B ⇒ C ∧ (D⇒ E))) with :

- A :⇔ ∃t: ( ∀x: A(x) ⇒ t ∉ T(x) )

- B :⇔ ∀y: H(y)

- C :⇔ t ∈ T(y)

- D :⇔ ( T(q) = T(y) \ { t } ) ∧ H(q)

- E :⇔ ¬ M(q)

- Now in D we can instantiate q to be a human. D⇒ E take the form "true => false" for a trait of our choosing and using P1. This makes D⇒ E False, which in turn makes C ∧ (D⇒ E) False.

- We apply the same trick in B ⇒ C ∧ (D⇒ E) by instantiating y to be human, which makes B ⇒ C ∧ (D⇒ E) False.

- Then by conjunction A ∧ (B ⇒ C ∧ (D⇒ E)) is False.

- Applying the last negation make the whole sentence True.

Since the choice of trait and human instance is arbitrary, the statement is vacuously True, meaning it can't be False in any structure that fulfils our mentioned predicates.

And if P2 is vacuously true, then P2 can be removed with no effect on the argument, which simply leaves

P1:⇔ ∀x: H(x) ⇒ M(x)

C:⇔ ∀x: A(x) ⇒ M(x)

i.e.

P1: Humans are of moral value

C: Animals are of moral value

An obvious non sequitur.

P2 is vacuously true if humans are considered to be in the set of animals

If we allow the definition of trait to be so broad that it includes the trait of 'being part of the set of humans', and we allow for this 'trait' to not be absent in animals (i.e. to be present in animals), then P2 becomes vacuously true. This is because it would imply there can be animal which is human i.e. ∃x:(A(x) ∧ H(x)) (there exists an x that is both human and animal). Subsequently there would be no trait that can satisfy both being absent in all animals and present in all humans. i.e. there is no 't' that can satisfy both '∀x: A(x) ⇒ t ∉ T(x)' and '∀y: H(y) ⇒ t ∈ T(y)'

This leaves us with a negated series of conjunctions of which at least one conjunction will be false. This makes the series of conjunctions false, and the negation true, hence P2 becomes vacuously true.

This is not an issue introduced by the FOL translation, it is present in the original argument itself by the requirement that the trait can be absent of humans, which of course 'being human' cannot.

To show this more formally, we can define the trait of 'being part of the set of humans' to be 'h' with,

∀x: (H(x) ⇔ h ∈ T(x))

i.e. for all x if x is human then x possesses the trait of being human, and if x possesses the trait of being human then x is human

Now the statement 'h is absent in humans' would be

∀x: (H(x) ⇒ h ∉ T(x))

which of course would be false, by the definition.

Note we could provide a very similar proof that P2 is vacuously true if 'moral value is allowed to be a trait' since by P1, it is also something a human cannot lack.

Separating humans and nonhuman animals

To avoid the above scenario we must change P2 such that we are now talking about humans and nonhuman animals (which is arguably implicit from the way Isaac presents his argument).

P2:⇔ ¬ ( ∃t: ( ∀x: (A(x) ∧ ¬H(x)) ⇒ t ∉ T(x) ) ∧ ( ∀y: H(y) ⇒ ( t ∈ T(y) ∧ ( ∀q: ( T(q) = T(y) \ { t } ) ⇒ ¬ M(q) ) )

note the addition of '∧ ¬H(x)'. Now by P1, we know that the only trait that if present in animals (or if not absent in animals), that would give animals moral value, is the trait of 'being human', which is not possible here. This is because for a nonhuman to possess the trait 'human' the statement

∃x(¬ H(x) ∧ h ∈ H(x) )

Must be true. But it of course is false because ∀x: (h ∈ T(x) ⇔ H(x))

Hence there is nothing in P2 to give all animals the trait 'human' nor is there anything to give animals moral value, so the argument is a non sequitur.

Showing the argument is a non sequitur

It is easy to show the argument is a non sequitur by imagining a case where P1 & P2 are true but C is not.

To do this we propose a case where humans have moral value, a nonhuman animal does not have moral value, and for all traits there exists a replica without the trait that has moral value. So in this case the following three statements are true.

- ∀x: H(x) ⇒ M(x) (All humans have moral value )

- ∃x: (A(x)∧ ¬ H(x)) ∧ ¬ M(x) (there exists a nonhuman animal that lacks moral value)

- ∀t (∀y: H(y) ⇒ ( ∃q: ( T(q) = T(y) \ {t} ) ⇒ M(q) ) ) (for all traits there exists a replica without the trait that has moral value)

Now we check this against the argument;

P1 is clearly true.

Now to check against P2. We know that for all traits there exists a replica without the trait, that has moral value. Hence the statement

∃t: ( ∀x: (A(x)∧ ¬ H(x)) ⇒ t ∉ T(x) ) ∧ ( ∀y: H(y) ⇒ ( t ∈ T(y) ∧ ( ∀q: ( T(q) = T(y) \ { t } ) ⇒ ¬ M(q) )

becomes false. i.e. the statement 'there is a trait absent in nonhuman animals and present in humans that if absent in a replica of a human without the trait, would make the replica valueless' is false.

So the negation of the statement becomes true (i.e. 'there is no trait ...' becomes true). Hence P2 becomes true.

Now C is clearly false because in this case there exists a nonhuman animal that does not have moral value. Hence it is possible for there to be a case where P1 and P2 are true, but C is not. Thus the argument is a non-sequitur

Showing NTT fails for disjoint sets in general

Suppose we have two sets, set A (SA) and set B (SB), and suppose that they are disjoint i.e. their intersection is the empty set i.e. SA ∩ SB = ∅

Now we make the definitions

- A(x) is true ⇔ x is a member of set A

- B(x) is true ⇔ x is a member of set B

- P(x) is true ⇔ x has property P (e.g. moral value)

- T(x):⇔ The set of traits belonging to x

We can note that the sets being disjoint is equivalent to ∄x (A(x) ∧ B(x)) i.e. there is no x that is a member of set A and set B

The NTT argument is equivalent to the following

- P1:⇔ ∀x: A(x) ⇒ P(x)

(All members of set A have property P)

- P2:⇔ ¬ ( ∃t: ( ∀x: B(x) ⇒ t ∉ T(x) ) ∧ ( ∀y: A(y) ⇒ ( t ∈ T(y) ∧ ( ∀q: ( T(q) = T(y) \ { t } ) ⇒ ¬ P(q) ) )

(There is no trait absent in a members of set B and present in members of set A, that if absent in a replica of a member of set A, that is not in set A, would make the replica not have property P)

- C:⇔ ∀x: B(x) ⇒ P(x)

(All members of set B have property P)

To show this is a non sequitur we present the following case where the following three statements are true

- (1) ∀x: A(x) ⇒ P(x) (members of set A have property P)

- (2) ∀x: B(x) ⇒ ¬ P(x) (members of set B do not have property P)

- (3) ∀t (∀y: A(y) ⇒ ( ∃q: ( T(q) = T(y) \ {t} ) ⇒ P(q) )) (for all traits, there exists a replica of a member of set A, without the trait, who has property P)

Now if we define the trait 'a' with ∀x: (A(x) ⇔ a ∈ T(x)) (for all x, if x is a member of set A then x has trait 'a' and if x has trait 'a' then x is a member of set A). And likewise the trait 'b' with ∀x: (B(x) ⇔ b ∈ T(x)). Now we know since the sets are disjoint ∀x: (A(x) ⇒ b ∉ T(x)) and ∀x: (B(x) ⇒ a ∉ T(x)). Essentially, 'a' is the trait of 'being in set A' and 'b' is the trait of 'being in set B' .

So we know when we consider the statement

∀y: A(y) ⇒ ( ∃q: ( T(q) = T(y) \ {t} ) ⇒ P(q) )

we know T(q) = T(y) \ {t} is a subset of T(y) i.e. T(q) ⊆ T(y). So 'b' cannot be contained in T(q) since it is not contained in T(y), so the replica cannot be in set B.

Now if we check these statements against the argument we have

P1: Clearly true

P2: We know that by (3) all replicas (who cannot be in set B) have property P. Hence the statement

∃t: ( ∀x: B(x) ⇒ t ∉ T(x) ) ∧ ( ∀y: A(y) ⇒ ( t ∈ T(y) ∧ ( ∀q: ( T(q) = T(y) \ { t } ) ⇒ ¬ P(q) )

becomes false. And P2 becomes true by negation.

C: Now since q is not a member of set B, the statement (2) still holds true, and C becomes false.

Thus we can show a case where P1 & P2 are true and C is false. So the argument is a non sequitur.

Now we have shown that NTT fails in general for disjoint sets, we can immediately say that for any disjoint sets such as the set of 'humans' and the set of 'cows', if we choose 'humans' to be the set of moral value, then NTT will fail to establish moral value in the set of 'cows'

Subsequent Verbal Versions of NTT

If we consider the analogy we used earlier, in which we substitute ' humans are of moral value ' for ' I am of moral value ' and demonstrate how NTT would fail to establish moral value in a cow called Bessie. The P2 given by Ask Yourself becomes equivalent to

- P2 - A trait-adjusted clone of me with traits identical to Bessie is of moral value

The first problem with this is that this P2 is not the same as the P2 given in the written version. Ask Yourself is incorrectly equating the following two statements:

- If a trait-adjusted clone of a human had the set of traits of a (nonhuman) animal it would have value

- There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to deem ourselves valueless.

In the second proposition we are considering traits, which if absent in humans, would make the clone valueless i.e. we are considering all beings with the set of traits; {traits belonging to humans} without {trait(s)} or more simply TH\ {t} not beings with the set of traits of an animal, TA . Now since these beings have a subset of the traits of humans TH\ {t} ⊆ TH, unless the traits of a cow (for example) are a subset of the traits of a human (they are not), the beings can never be cows. This is shown in more detail in the section showing NTT fails for disjoint sets in general.

Note here '\' represents 'without' e.g. {a,b,c,d,e} \ {d,e}={a,b,c}. Adding traits would require the use of the operation 'union' denoted by '∪', with {a,b,c} ∪ {d,e} = {a,b,c,d,e}

Misunderstanding the law of identity

Ask Yourselfs claims that "two objects of the same traits are the same object" and "to ressist this is to deny the very first law of logic, which is the law of identity". However it's not the case. The first claim is a principle known as the identity of indiscernibles, which says: if for every property P, object x has P if and only if object y has P, then x is identical to y. Or in the notation of symbolic logic:

(∀P)(P(x)⇔P(y)) ⇒ x=y.

One cannot use this principle without stating it as a premise. Let's also observe that the law of identity simply says that x is identical to x for each x and it has no use in the context Ask Yourself is speaking about unless two objects x and y are equalized somehow in the first place.

Failure to engage with formal logic

This is not in any way an attempt to obscure the reasoning by using a different language. Ask Yourself responded to the youtuber 'non-ethical vegan' (who tried to provide him with a proof that the NTT argument is a non sequitur by using propositional logic) by claiming that 'This is like Chinese to me, please explain in English'. It is not our task to validate or invalidate such proofs, instead we should recognize the failure of Ask Yourself to accept the validity of the approach. The English language is not suitable to prove or disprove formal arguments. It is however more than enough for informal ones. We already know that FOL (first order logic) is complete and sound, so it is a good candidate for exposing any expressive argument. Failure to translate into FOL will not convince anyone serious about the matter. This also applies for mathematical theorems, most of them are stated in an informal way, but if a peer is not convinced, the job of the mathematician is to dissect the theorem and eventually translate it into FOL. Granted this is not often done (major theorems would be pages long ...), but in the case of NTT it is easy to do so.

Itemized Issues Discussion

With the argument itself

All Humans

P1 only says humans have moral value (implicitly all humans), not that only some humans do.

P1 - Humans are of moral value.

Human may range from vegetative states to a fertilized egg, and for "conservatives" who believe those have intrinsic value there's common disagreement that violent criminals have moral value (still human).

This in itself seems to contradict the notion of a value giving trait other than the arbitrary "human" status.

If you want value to be based on another trait, your first premise can't make that impossible.

Isaac has permitted that other premises be substituted in for P1 (such as "I am of moral value") and maintained that the same conclusions can be reached. This premise is easy enough to correct, although the argument still fails even when limited to personal moral value.

P2 Inconsequential

P2 says there is no trait of such description:

P2 - There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to deem ourselves valueless.

But even if so, there is no premise that says moral value must be based on such a (implicitly natural) trait at all or that it can not be an arbitrary one (if one chose to name a trait). Moral value could just be fiat, or the tautological and irreducible non-natural trait "moral value" itself.

P2 can be variously ignored or rejected in many ways.

A perfect logician could accept that P1 humans are of moral value AND P2 that there is no such trait, but still reject the implicit concluion: that animals are of moral value.

As such, the conclusion does not follow from the premises; the argument is a non sequitur, chiefly because P2 fails to do what Isaac thinks it does.

Isaac's first defense

Isaac's first defense asserts, in a manner indicating that he doesn't understand literally the first thing about logical arguments (the function of premises), that "arbitrary" can be eliminated as a possibility by (paraphrasing)"feeding it back through the argument" or "trying to plug arbitrary justifications into the argument".

While this may follow from his tricky usage of invalid generalizations, or simply his misunderstanding of what a "logical contradiction" means (he thinks it means a double standard), this defense appears to be a form of circular reference, where he tries to support a failed premise by appealing to another unstated variation on that premise (or another version of the argument in entirety) to provide the support it needs.

See Circular References Here for more explanation of this issue.

The Brick Analogy

(defending against non sequitur criticism)

The "Brick" analogy is one he gives as a defense, attempting to show how the need for his version of consistency is grounded in objective reality and doesn't need to be supported by a premise.

If you're saying that a creature has moral value and you can't distinguish that creature from can't distinguish another creature from that creature in a way that would if true of the first cause you to say it doesn't deserve to have moral value then you're contradicting yourself by actually suggesting that that second creature does not deserve value as well. So if that's too complicated for you to understand you can just do it with physical objects, OK so: I can(n't) lift brick A um there's no difference between or no trait you know present in uh brick B which if true of brick A would make it possible for me to lift brick A so therefore it's contradictory to suggest that I can lift brick B. Well of course that's true. And if there were such a trait if brick B could be lifted then whatever makes it liftable if you map those traits over to brick A then you could lift Brick A too. So this is just a basic formula to discover contradiction.

1. It is not actually a contradiction in the strict logical sense for it to be the case that (i) I can lift brick A, (ii) there is no difference between brick A and brick B, and (iii) I can't lift brick B. There is nothing in the logical form of these propositions that makes it the case that they can't all be true together. Indeed, it seems conceptually possible for (i) and (ii) to be true and (iii) to be false - if the world did not work according to anything like the physics of our world, it could simply be a basic fact about the universe that you could lift brick A but not brick B.

2. Comparisons with physical reality and contradictions in physics only makes sense because forces like gravity apply the same universally, something you cannot just assume for morality or moral standards. If forces like gravity could be regarded as subjective, the whole brick lifting issue would become much more complicated. By making these physical analogies Isaac is committing the argument to hidden meta-ethical premises of some form of naturalistic moral realism (a good position to commit to, but it must be stated in the premises to make the argument valid).

3. Also, it's trivial to name the trait in the brick too if you don't require it to be a natural "mind-independent" one, for example:

"I'm unable to lift that brick because I don't want to. I'm unable to lift things I don't want to lift because I lack the motivation and motivation is necessary for lifting things. The trait is that I want/don't want to lift it."

In essence, arbitrary whim is just as adequate an explanation to differentiate Brick A and B as any UNLESS as explained above you make certain meta-ethical commitments against arbitrary answers and establish some form of moral realism and reject any subjective factors (a.k.a. actual moral objectivism, not Isaac's false dichotomy version). Again, these are good premises to establish and that can create strong arguments, but Isaac has consistently rejected the need for them while presenting analogies to justify that lack in #NameTheTrait that also fail without such premises.

Earlier Informal Versions

It's important to note that in an earlier informal version of this argument, Isaac used to premise the argument with a claim like "Either you believe actions must be justified, or you don't", allowing that his argument only applies in the former case: this served as an appropriate premise (given a reasonable definition of justification) grounding morality in that justification and functionally forbidding arbitrary standards. It was a much better argument in the past. The formalized version he later presented discards this essential premise in an ill-conceived attempt to make the argument apply to subjectivists and relativists as well, but breaking the argument in the process; for more on this see Meta-Ethical Independence Here.

It's not clear if the fact that earlier and less formal versions were logically superior is some kind of vindication of Isaac, or actually makes this all the more ridiculous because he supposedly spent time and effort changing these arguments to make them logically invalid. He started as an outlier among vegan youtubers, making fairly compelling arguments and being relatively personable, and has reversed course entirely. It may be inevitable that the disjoint correlates to his growing fandom; with cult-like adoration often comes a failure to engage usefully with criticism.

Analogies can be found in hollywood[1] where fame can lead to overconfidence, as well as in modern politics where political echo chambers promote polarization and sabotage useful bipartisan policies[2].

Something to think about, but it was important to note that this was not always the case and why.

It's possible that Isaac is uniquely resistant to reason and criticism, but that's too easy of an excuse because this can also represent a failure on our part (as the skeptical side of the vegan community) to engage with criticism sooner before he became so invested in these arguments (he now believes #NameTheTrait is responsible for his youtube success, and seems to believe admitting any flaw in it or revising the argument to correct those flaws would destroy him).

Existential Meaning

"Human" and "us/ourselves" in this argument has no clear meaning:

"P2 - There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to deem ourselves valueless."

Any example of a trait applied to you (like having your consciousness transferred into a biologically non-human body) might just cause us to change our understanding of what human means (anything with a human consciousness) to maintain consistency so that nothing could cause you to stop being human, even "once human always human" (even the trait "Having been human at some point"), thus making "human" an unfalsifiable answer for moral value, or the change may cause us to reject the application of "we" to the new entities (e.g. reduced to the intelligence and capacity of a cow, we may consider what makes us ourselves to be gone and this to be equivalent to death anyway), such that the opponent need take no issue with the loss of moral value making P2 false.

Isaac is concerned with the "hard problem" of consciousness, so he probably isn't prepared to tackle this issue. The easiest way to fix this problem is to avoid references to "us" by defining clearly the behavioral implications of "lacking moral value", or just scratch this confusing wording and substitute in directly the golden rule. Unfortunately, this runs into the next problem which Isaac is unwilling to address:

Meaning of "moral value"

"Moral value" has no clear meaning or material implications. This is easy to fix, as noted above: it just needs to be grounded in some meta-ethical premise.

Unfortunately, Isaac is unwilling to do this (and has even removed grounding from previous informal versions of his argument) seemingly because he believes it is the subjectivity of this provision that makes the argument work for subjectivists. He thinks it's up to whatever "you" think gives moral value, and you just have to be "logically consistent" with that. And if he actually abided by that, his argument would have no normative persuasive power at all.

In practice, it's this ambiguity in the argument he uses to manipulate his opponents, supplanting his own unique definition of consistency/contradiction to relate to double standards in imposing your will upon others in ways you wouldn't want to be imposed on. Instead of being honest enough to just put that in the argument as a premise (as recommended above) he changes the rules of logic itself and the very definition of "logical contradiction" to suit his agenda.

Obviously, in philosophy a "logical contradiction" is not the same thing as a double standard. See Logical Contradiction Meaning for more info on this.

All/Some Animals

Given the qualifier "All" for animals (there is no trait absent in all animals which if absent in humans) P2 is trivially true, because humans are by definition included in the group "all animals".

Given the qualifier "some", P2 is clearly false when non-sentient animals are included (assuming the premise about human value were corrected). Animals range from sponges to humans, and do not broadly share any trait beyond phylogeny (like with "humans" as a blind category).

Isaac means the argument to prove moral value for all animals that lack moral value giving traits, but the argument does not do this. If he wanted to do this, the argument should be formed very differently.

This specific problem in the argument could also be corrected by specifying it should be applied to individual animals, or those in like groups based on the evaluative trait.

Like the issue with "human" in P1, this is not a difficult issue, but the lack of rigor here generates ambiguities and contradictions in the argument. Of course, this may seem like a rather minor issue after point #4, but no fallacy is too small.

Even correcting for this point, the argument fails as a non sequitur due to the lack of premises to support P2 and other issues as explained at length under other points.

Part 2 Same Problems

The second part of the argument fails in the same ways the first part does, in addition to:

Value Spectrum

The first part of the argument, if corrected, might establish animals have some value, but does not establish equal value in part one. Part two then attempts to take that spectrum of value and convert it into an absolute: non-exploitation. It should convert a spectrum of value into a spectrum of acceptable exploitation, from no value = total exploitation fine to fully functioning human level value = no exploitation acceptable. Logically, animals like cows would lie somewhere in between where some exploitation would be acceptable, while their interests would also have to be considered somewhat to limit that exploitation (i.e. animal welfare, which already exists and does not necessarily conclude in veganism).

Pt2 P2 Empirically False

P2 in the second part is also just outright empirically false for the vast majority of people in two ways, and in addition causes issues in debates due to perceived hypocrisy, depending on how you look at "exploitation":

The action or fact of treating someone unfairly in order to benefit from their work. -Oxford English Dictionary[3]

The distinction hinges on "fairness"; in a general universal sense of denying the fairness of bad luck or ensuring the arrangement is legitimately in the interest of all of those being used, or based merely on the rules laid out in law by society?

A. In the general sense

Nothing short of non-exploitation is considered adequate? Incorrect.

P2 - There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to consider anything short of non-exploitation to be an adequate expression of respect for human moral value.

The absolutist language is a serious problem here, but it's also the only thing that ties in strict veganism without taking the care to present any empirical argument.

Only a minority of people (largely Marxists) oppose any measure of human exploitation in principle, and people (even most Marxists) certainly don't show agreement in actual practice - we literally consider it an adequate (not ideal, even if just tolerable for some) compromise every day we accept it and function in society rather than abstaining in protest.

If you want to dilute the definition of "inadequate" to include some far-off goal of changing it without any meaningful abstention in the present, then most meat-eaters are already vegan by the same standard that armchair Marxists are already political revolutionaries despite eating meat and working an ordinary 9-5 respectively.

Is that the standard we're after?

Is all you have to do to be vegan is find animal agriculture troubling in some abstract way, imagine some day it will all be different, and post a couple things on Facebook about it?

If not, obviously P2 fails by virtually any trait, because we already DO consider something "short of non-exploitation to be [...] adequate".

You could argue that it's more practical to go vegan than to abstain from capitalism, but some rare people can and DO make efforts to do the latter so it's obviously not impossible to work at it. However, this argument is not about practicality at all: it's about extremes. It's about non-exploitation, not limited exploitation to the extent we find acceptable because it benefits society as a whole (like regulated capitalism, for those of us non-Marxists) -- that would come back to the welfare issue and lead into an empirical argument about whether the exploitation of animals is justified by the overall benefit to society (I don't think it is, but nothing in the #NameTheTrait argument presents that and Isaac doesn't even think it's a valid question to ask).

It's not clear if Isaac (a vehement "anti-SJW") would be personally willing to bite the bullet on that one and accept Marxism and radical Social Justice as co-implications of making this premise work, and admit that they are equally necessary along side veganism.

Given how often he has spoken against hitching veganism to social justice, it seems unlikely he would switch sides on that one and take the intersectional approach just to defend this formulation of #NameTheTrait.

Either way, even if all of the other problems in this argument were fixed or ignored, the inclusion of this premise inherently excludes all but Socialist Social Justice advocates. And given Isaac's primary audience and outreach is to "anti-SJWs", it's a fatal flaw in the argument's utility.

B. In the narrow sense

(The narrow sense of playing by the rules of society)

Some of these rules are absolute and we do not accept violations of them, but they are based on social contract, NOT on expression of human moral value.

For example: According to social rules, it's wrong to steal a million dollars from a billionaire who hoards or wastes it (which would be an "exploitation" the billionaire didn't consent to) in order to save the lives of hundreds of people.

It's even wrong to harvest the organs of a dead person who no longer needs them to save a dozen lives unless the person consented to be an organ donor.

It's also perfectly acceptable to target people you know are not financially responsible to offer them credit cards, and then garnish their wages to milk them indefinitely for the minimum payment on that TV they didn't need.

All in the rules of the game.

Exploitation only occurs in this sense when a contract is violated or laws are broken.

Rules of legal justice are not there because they are morally right in every instance, but because of the social utility; because we, as members of the social contract, value our own consent and property rights over total harm. They're ultimately self interested.

These bounds are not there because people don't want to be unduly exploited, e.g. contract law, no human trafficking, etc.

Isaac would argue that if you don't want to be bought and sold (by somebody from another culture where you're in the out-group, or an alien), that creates a contradiction if you would permit others to be (based on #NameTheTrait) unless there's a trait that separates you and the others that if true of you would make you OK with being bought and sold.

Again, #NameTheTrait is not a valid argument. It doesn't contain premises that forbid arbitrary distinctions, and it doesn't contain premises that necessitate naming traits (it only meaninglessly claims there isn't one). Appealing to another iteration of a broken argument in order to fix holes in the same broken argument doesn't work. Just saying there isn't a trait is fundamentally different from claiming moral value must be justified by such a trait, and different again from claiming that behavior like this which isn't even linked to moral value must be justified by one regardless of moral value.

If an alien bought and sold you, then of course that would be against your social rules which are engaged in to protect humans, and human society would fight the aliens because humanity is self interested. Not wrong, just against the rules of human society. The alien society and the human society might, by treaty, come to terms where they agree not to buy and sell each other, and by this means the social contracts would be unified and it would become a violation of the rule (exploitation) to use an alien like that. The idea that two distinct social contracts (not morality) could be at odds with each other when they serve different populations is not a contradiction.

While there are some vegans involved in an intersectional vegan form of social justice who would disagree (And I would be surprised to learn that after all of his criticism of "SJW"s Isaac is one), the fact of people buying and selling cows does not seem in any readily apparent way to increase the chances of you being bought and sold. Empirically, justice does not seem to be an every sentient being or none game, and at least most people don't think it is one.

This would make the second part of P2 irrelevant:

P2 - There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to consider anything short of non-exploitation to be an adequate expression of respect for human moral value.

And it would either mean that animal agriculture is not exploitative because it is permitted by the arbitrary rules of society with certain limits on welfare (just as slavery would not have been exploitation before abolition; it was your bad luck to be born a cow or a slave), or outside of legal bounds it would mean "exploitation" of animals is meaningless because they have no status in the game by which to evaluate whether they are or are not being exploited according to the narrow definition of social contract.

Either way (ignoring the fact that the whole argument is a non sequitur), if the trait being asked for is meant to justify why forms of exploitation that would not be acceptable for humans are acceptable for animals in the general sense or why the same actions ARE exploitation for humans and not for animals, the social understanding would provide just such a trait P2 claims doesn't exist: Societal Membership Status.

This is not a basis for morality or moral value at, but it is the basis of societal rules and if that's what you're basing actions on then none of this is even a double standard.

--

This is obviously not an issue with the validity of the argument (a false premise doesn't mean the logic is wrong), but it is a serious issue with the soundness. Also, when a premise is this obviously incorrect for the vast majority who don't hold absolute views it creates problems for the perception of the argument (you might as well include a premise about the Earth being flat).

If Isaac were willing to embrace intersectional social justice, he might actually get pretty far with this argument within that limited circle, but it's counterproductive for the internet and society at large where people don't generally agree with the politics.

But even if we restricted the argument to social justice advocates who will be most inclined to agree on those points of justice, and even if we added in the necessary premises to make this P2 and the P2 from the first argument function, and fixed all of the other problems, you're still left with the fact mentioned above of the gradient of moral value. The only "fixing" of this argument to avoid that is to either normalize moral value by somehow asserting all beings of moral consideration have the same moral value, or by ignoring it completely and normalizing outcome despite drastic differences in moral value (which obviously makes the spectrum of "moral value" irrelevant).

Neither of those outcomes are desirable unless you're trying to create an army of fundamentalists who consider exploitation or murder of an insect as severe an infraction as that for a human being because they both have an interests.

C. Issues in debates

Hypocrisy does not mean somebody's point is wrong, but it does in practice makes people unlikely to consider the advice or condemnation of an apparent hypocrite due to the seeming dishonesty and lack of sincerity suggested by actions at odds with claimed beliefs.

These issues have actually been problematic for Richard (Vegan Gains) in debates, who has professed to agree with NTT. When posed with questions such as 'Was exploitation involved in the production of your phone, if yes, why do you not boycott such products?', his answer usually takes the form; yes exploitation was involved, but I need them for my activism, income and youtube videos, and is not immoral for me to do so. All of these are good reasons, however it shows that he does not consider the absolute of 'nothing short of non-exploitation' to be an adequate expression for human moral value, as pragmatic considerations take precedence. And if pragmatic considerations take precedence, then it's an empirical cost-benefit analysis, and not an absolutist argument like this that is useful.

An example of this was during the Warski debate, in which, on the subject of technology Richard stated 'you can justify some amount of exploitation in that sort of area of your life'. Isaac was Richard's partner in this debate and it's fair to say that he agreed.

A similar issue arises when posed with questions such as 'Do you avoid all things produced using animal products, or products that may contain trace animal products e.g. glues etc.?'. Again the answer is no, and it that it is not immoral for me to do so. Which, similarly, means that he does not consider the absolute of 'non-exploitation' to be an adequate expression for animal moral value.

It's worth noting the definition of veganism used by most vegans, including Richard, is

'A philosophy and way of living which seeks to exclude—as far as is possible and practicable—all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing or any other purpose; and by extension, promotes the development and use of animal-free alternatives for the benefit of humans, animals and the environment. In dietary terms it denotes the practice of dispensing with all products derived wholly or partly from animals.'

which is not absolutist in nature.

Fans of Isaac may think you can resolve such issues using the golden-rule, by answering 'yes' to the question 'would you accept the exploitation if you were the victim in these cases?'. There are two issues with this:

I. This would not be relevant, as the argument as framed requires the absolute of non-exploitation. The argument could be rewritten (and Isaac seems to think other variations can be substituted on the fly in discussion) to separate various categories of exploitation (for food, for other products, etc.), but even if so:

II. It seems at least very unlikely that people would be willing to be killed to make glue to bind books, etc. When in practice Isaac demands this kind of assent to validate any action, it fails because nothing is likely to justify requiring our deaths short of some dramatic heroic sacrifice (some people might be willing to die to cure cancer, although it seems unlikely that a cow would be concerned with this and be willing to make that noble sacrifice).

Isaac or Richard can try to make the distinction between products (for which the animal was actually killed) and byproducts (for which the animal was not killed), and claim the latter is not exploitation because the animal has already been killed and a corpse can not care. Again, there are two issues with this:

1. It would mean that once the primary product was identified (e.g. beef), all other products would be vegan, from gelatin to leather to brain, organ meats, bone broth, etc. Possibly even quite a few processed meats, all of which are to various degrees byproducts.

2. The product-byproduct distinction is actually a spectrum, not a dichotomy. All products that are sold contribute to the profit motive to raise and kill the animal; they are all reasons to do so, and use of byproducts subsidizes the primary products to make them cheaper and push them into the market just as consumption of primary products subsidize the byproducts. There's no fundamental, categorical difference between use of glue as a binder and eating a steak; they're differences of degree of exploitation.

Given these considerations, it's clear that Isaac's answers don't resolve the absolutism demanded by this argument. In accordance with this, everybody would be engaged in "logical contradiction" (if the argument were valid). And because logical contradiction itself is not a spectrum (see principle of explosion), either you're logically consistent or you have a contradiction, and that makes everybody equal with respect to the only normative compulsion of this argument (for those who want to avoid "contradiction"), from the most obsessive of personal purity vegans to the most ravenous carnist. If there is no distinction between the two, the argument has no normative force at all, and it has no utility to anybody (even if we fixed all of the other problems).

In practice, and with the defense of the argument

Most of these issues have been covered in brief above, but since they're tucked into the discussion of Isaacs claims about the problems (which are very limited to a few brief assertions, and otherwise must be derived implicitly from his arguments in practice) this section will outline them openly and in more detail

Circular References

(Or infinite regress)

NameTheTrait is a non-sequitur as stated, but rather than correct the argument Isaac has employed some very bad arguments supporting it which only commit him more strongly to a varied assortment of fallacies.

None are more transparent or easy for the layman to grasp than his seeming circular references.

In short, Isaac claims you don't need any additional premises to require justification at all, much less to require justification by a non-arbitrary trait for P2, because P2 creates those premises:

P2 - There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to deem ourselves valueless.

And according to him, this is because you can take something like "arbitrary value" or "fiat" and just (paraphrasing)"feed it through the argument" to show a contradiction. "You wouldn't accept arbitrary so you can't use arbitrary" (something he only allows if you would "accept" it)

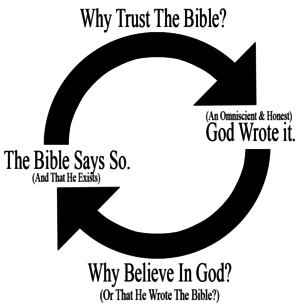

In this way, by referring to an alternative version of the failed premise itself, this is comparable to the common theological circular reference to prove god from scripture and scripture from god, e.g. justifying the existence of God by referring to the Bible, and giving the Bible authority because it's God's word as demonstrated by the Bible. (#NotAllChristians, of course)

A more precise analogy that indicates more clearly the absurdity of the #NameTheTrait claim is this one:

| Argument: | #NameTheTrait | #NameTheVerse |

| Formula: | P1 - Humans are of moral value P2 - There is no trait absent in animals which if absent in humans would cause us to deem ourselves valueless |

P1 - Humans are of moral value P2 - There is no verse absent in the Bible needed to deem God's exclusive right to dictate infallible moral law |

| Missing Premises: | P3 - Such a trait can not be arbitrary P4 - Moral value must be justified by such a trait. |

P3 - A moral-giving God actually exists P4 - The Bible is the infallible word of said God |

| Response: | No you f*cking retard, just feed it back trough the argument.

There's no trait absent in animals that would let you use arbitrary to devalue them that if absent in humans would make you accept arbitrary devaluation. It's so obvious you idiot. |

You're mistaken beloved friend, just feed it back through the argument.

There's no verse absent in the Bible that would be needed to prove it deems God's moral giving nature, existence, and infallible word as the Bible. Please join us in prayer. |

- Note that no Christians actually use a #NameTheVerse argument, this level of transparently bad logic is not to be found among even the worst apologists.

If Isaac was trying to write P2 in a way that made it recursive and generalized the rule by removing it from subjective context, he failed at doing so. This is NOT how the premise is written, and it obviously does not achieve this if you plug in arbitrary traits provided they are worded clearly; it's still a non-sequitur, and doesn't provide an out to arbitrary answers to the claim there's no trait allowing arbitrary (a potential infinite regress).

It's also important to note that IF the premise actually were written like this, it would be a lot easier for people to disagree with directly. As it is, like in the theist example, P2 is relatively non-controversial for most people because it's merely a fact statement (for example, about what is written in the Bible, or about animal physiology).

The issue with the theological version is probably more obvious: in order to be true, a claim about the Bible being true or saying anything with absolute credibility (like that god wrote it) must be premised by an assumption that such a God exists and actually wrote the bible in the first place (and didn't lie, and knew what he was talking about, etc.). Without that premise to start with, the argument fails and can not substantiate itself (i.e. by referring back to the existing unfounded assertion that the Bible is true).

With #NameTheTrait, likewise, in order to function in the first place P2 must be premised by certain claims that we need to justify moral claims at all (to stop it from being a non sequitur) and further that they should be justified by non-arbitrary traits (to make dismissal non-trivial).

If such premises were included (as in the corrected versions), the argument would not need to be self-referential for support, and without them it can't provide that support to itself because this golden rule/anti-double standard aspect Isaac claims never manifests. As it stands, the argument only makes the assertion that you wouldn't consider yourself valueless if you lacked a trait lacking in animals, which is not relevant. This may create a double standard, but a double standard in itself is not a logical contradiction, and nothing in the argument establishes the meta-ethical relevance of that (such as by making assertions of fairness or justice in morality). To equate a double standard to "logical contradiction" is an extreme misunderstanding of the meaning of logical contradiction explained here.

Isaac Claims that is it not the specific arbitrary claim that must be compatible with P2, but a generalized form, as such this fallacy could be partially explained by his invalid generalizing, but this does not seem to be the whole of the story because these self-referential claims go beyond that to dismiss the need for the supporting premises necessary to make P2 function at all (although this could in part be explained by his radical misunderstanding of the Meaning of "logical contradiction").

Given the sum of his other fallacies, his dismissal of criticism with apparent circular references may seem superfluous, but it's a good example of the standards of argument he employs.

Independence from Substantive Ethical Premises

Isaac claims this argument works on the basis of essentially no substantive ethical premises other than (1) one's view that one is of value - as manifest by one's resistance to being killed - and one's (2) conviction that one would not lose value if one were to lose any of the traits that one currently has but (sentient) animals lack - as manifest, it seems, by one's simply wanting not to be killed if one were to lack those traits.

If true, that would be extremely impressive - particularly if one were committed to valuing oneself simply in virtue of one's having a desire / propensity to resist being killed. It might be the most impressive argument created for anything in philosophy, let alone veganism. As is often the case, if something seems too good to be true it probably is.

Unfortunately this desire for a one-size-fits-all argument has led him to an argument that fails in so many ways it achieves a state of fractal wrongness -- outlined in issues. The attempt to dispense with dependence upon substantive premises found in other normative arguments in order to create the best argument ever has instead resulted in what is at best a failed attempt to dispense with such premises (which ends up looking a lot like the argument from less able humans / "marginal cases") and what is at worse an extremely unconvincing argument. Some speculate that his rejection of corrections and insistence in his argument's soundness in its present form is a consequence of that monomaniacal focus on independence from substantive ethical premises (others may attribute it to general arrogance and refusal to admit to errors of any kind).

However, calling something independent doesn't make it so. The way he uses this argument and the way it's *supposed to* work (despite its non sequitur and other fallacies) demonstrates a series of hidden premises. And while some of these hidden premises Isaac agrees with -- even claiming a few are just definitions -- he doesn't realize the substantive ethical implications of these hidden premises, and how they contradict his own claimed positions.

For his part, on a personal level Isaac He claims to be a moral subjectivist (specifically an "ontological subjectivist, and an epistemological objectivist"), his definition of these terms is colloquial and incorrect in the context of philosophy because it generates contradictions and false dichotomies of its own (see objective-subjective distinction), but where it really stands out as a problem is its conflict with the substantive ethical assumptions necessitated by #NameTheTrait (if it is to function in any capacity the way he believes it does), and more specifically a conflict with his own deontological views).

Brief outline of necessary substantive ethical assumptions:

- Rejection of value on the basis of arbitrary traits. Obviously P2 needs another premise to function, although Isaac believes some kind of circular reference is adequate instead.

- Assertion of the view that non-arbitrary traits must be traits such that, if one were to lack them, one would be willing to agree that one would lack moral value. This may be functionally because he believes a double standard is a "logical contradiction"

- Assertion of one's having moral value, and one's having it even if one were to lack certain traits. He does not seem to realize that one could desire to be treated in a certain way even if one did not have value that would give others good reasons to treat one in that way. E.g. he seems to have overlooked the response 'I don't have moral value; you'd be justified in killing me, it's just that I reasonably don't want that to happen - much like, if we were in a chess game, and you were about to check-mate me, you'd be justified in doing that, but I'd reasonably want that not to happen.' In practice, this may be due to his denial of valid dissonant actions, but can also be derived from his brick analogy.

- Assertion of deontological moral evaluation due to assertions of P2 in the second part of the argument.

Beyond his actions and claims which clearly indicate these positions, the mere fact that Isaac believes that it is possible to construct any kind of persuasive and logically valid normative argument outside a specified meta-ethical system should be demonstration enough.

Logical Contradiction Meaning

Isaac seems to believe "logical contradiction" means the same thing as a double standard. His followers have claimed this more explicitly, and he regularly uses this example to dispute claims like "human" as the source of moral value (paraphrasing):

"What if aliens came to Earth to eat Humans because they aren't aliens, would that be OK? Would you give in and let them eat you, or resist them? If you would resist, you're contradicting yourself."

Claims like these indicate double standards, but they do not indicate contradictions:

1: It is wrong to kill a human

2: It is not wrong to kill an animal

3: It is wrong for an alien to kill a human

Doing something to others based an an arbitrary reason (like your species) and opposing others doing that based on a similar reason is a double standard, but it is not a logical contradiction. A logical contradiction requires a direct negation. For example, any of these claims would create a contradiction with the set above:

1. It is right to kill a human

2. It is wrong to kill an animal

3. It is right for an alien to kill a human

An arbitrary moral assertion without objective substantiation can easily promote double standards because most people don't like being treated like that, and while it is without substantiation it is not a logical contradiction; you can even arbitrarily assert a moral system AND further assert that it's the only true moral system and all others are false. Is this unreasonable? Yes. But is it a logical contradiction? No.

To put this in context of the alien example Isaac likes to use: "If aliens came to the Earth and killed you based on their arbitrary morality, would you be OK with that?" the response it simple, "No, because they are wrong and I am right. My arbitrary morality is absolute true universal law, and theirs' is false."

Ridiculous? Yes! A logical contradiction? No.

Isaac either does not understand the definition of a logical contradiction, or he chooses to ignore the actual definition substituting in his folk definition instead. Isaac believes, or claims to believe, that folk definitions of technical vernacular are perfectly fine to use in a philosophical context even if they completely rewrite the rules of logic and argumentation in the process; if that's the case with this substitution, this is not only malpractice, it's transparent intellectual dishonesty; a pseudo-philosophy of the worst kind, a conscious twisting of definitions as incredible as the pseudo-scientific machinations of Deepak Chopra.

Once you have so flippantly thrown out the fundamental rules and definitions in philosophy and substituted in your own custom "logic" for the real thing, there's just no arguing the case. Isaac wholly rejects logic and supplants his own creation to justify his fallacious arguments, and intentional or not, the result is deception.

What's worse is that beyond holding these incoherent folk definitions, Isaac also commits straw-man fallacies and mischaracterizes his opponent's argument by generalizing claims like "humans" vs. "animals" to "species" to make them appear more in contradiction, but this is not valid:

Invalid Generalizing

In practice the way Isaac tricks some people in debates is by taking what they say and twisting the wording just enough to seem to mean the same thing, but slyly generalizing it so as to create the appearance of not being a trait exception.

For example, by replacing an arbitrary fiat of human value with something about the victim of an offense being of a different species: "Are you OK with being eaten by aliens?" is a common reply.

Isaac is either ignoring or not understanding that the claim that the value is "humanity" is absolute; the aliens are wrong according to that, the value given is not "is a different species". He tries to generalize the statements like that, by saying "species" instead of specifically "human species", to create the appearance of a contradiction where none existed (because it was only double standard, not a logical contradiction)

The deformation of arguments committed by Isaac is a form of straw manning.

When an opponent says:

1. It is wrong to kill a human based on species

2. It is right to kill an animal based on species.

This is a double standard, but it is not a logical contradiction. Isaac follows this by asserting something like: "You contradict yourself by saying it is not ok to kill Y based on X and then deploy it as ok to kill Y based on X", and he is making a generalization of the argument that is nowhere to be justified. It is not allowed to have a deduction rule of the type:

∀x: H(x) -> ¬K(x) ⊢ ∀x: ¬K(x)

∀ : for all

H(x) : x is human

¬ : not

K(x) : ok to kill x based on <insert any justification here>

⊢: entails

That is to say, you cannot have a deduction rule of the type; for all x, if x is human then it is not okay to kill x based on some justification, entails for all x it is not okay to kill x based on the same justification. You can't generalize the argument because it has been constrained to the set of humans. And the follow up argument of " please differentiate human and animal ... " doesn't apply because nowhere in the argument is it said that if you can't differentiate then the treatment should be the same.

It's possible that in doing this Isaac knows what he's doing and is trying to play word games and misrepresent people's answers to trick them, but whether he's doing it accidentally or intentionally the outcome is the same: it's intellectually dishonest, and he continues the practice despite being alerted to these problems.

Dissonant Actions

In practice, Isaac demands certain responses (on pain of being accused of "logical contradiction") must result from considering oneself to have no moral value. He demands such specific responses that he thinks permits him to accuse people of contradiction on the basis that they might dare to defend their own lives if (for example) attacked by aliens.

However, this is not necessarily the only viable outcome from "lacking moral value", and as explained above under Meta-Ethical Independence it has some serious implications.

In a logical argument, all potentially controversial terms and claims must be properly established by premises, not hidden. Moral value only equates to self defense if you link it to personal value in general by definition, which is begging the question.

It's possible that Isaac doesn't even understand that people can accept something as ethical but still not do it (as though ethical normative forces were absolute). This is ALSO not a "logical contradiction"; it means people have multiple values that compete for behavior, and the most ethical option doesn't always win.

Even if we believed aliens were in the right to come to Earth and eat us, that doesn't mean we wouldn't try to save our lives despite that. Even if we believed resisting were morally wrong, resisting would not be a contradiction: it would only indicate what most people will already admit: we are not 100% moral with no regard for self preservation. Most people will do some otherwise pretty immoral things by their own admission to save their own lives.

It also doesn't mean we'd be in the wrong to save our own lives. People usually don't claim farmed animals are in the wrong for resisting, so these actions may not even be dissonant at all based on a more complex definition of moral action (one that nothing in the argument's premises rebuts). This doesn't even require a double standard.

To make that line of "would you resist the aliens?" reasoning work and accuse contradiction with carnism if people answered in the affirmative, a premise would have to be added to alter the argument, defining "consider ourselves valueless" clearly in behavioral terms as "not try to defend our own interests". And of course that really narrows down the meta-ethics the argument applies to, and from there is is by no means meta-ethically independent.

Personal Contradictions

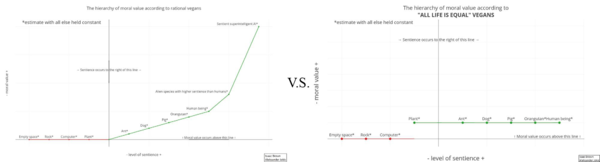

He has for some time claimed to believe that animals exist on a spectrum of moral value from the least to the most, which could be plotted on a rising curve relative to sentience (or something like that). He has claimed that the vegans who assert equal value for all animals are irrational and make other vegans look bad. Both of these are sensible claims, and the images he has produced to illustrate these claims are clear and depict a moral system that very much favors rational value-based calculations.

However, recent comments and the second half of the #NameTheTrait argument indicate a very different perspective on moral evaluation.

The problem people typically have with consequentialism is usually in being short-sighted: they have looked at some of the immediate consequences, but have ignored systemic and long-term consequences, or have generated a false dichotomy and failed to examine alternatives.

Isaac expounds his rejection of (and misunderstanding of) consequentialism in more (grusome and sexually disturbing) detail:

yeah I reject just absolute consequentialism as any thinking rational person should okay if you are a pure consequentialist then you would have to accept a ton of absolutely barbaric nonsense so for example if you can save five people's lives by killing one against their will and harvesting their organs you'd have to say that that is ethical if a bunch of guys raping a girl is going to generate more well-being for them than its gonna generate suffering for her maybe they roofie her or something like this you would have to say that the ethical thing to do is to rape her so if you don't accept those kind of situations then you're not a pure consequentialist

In the "rape" case, the answer should be incredibly obvious: Not raping, and doing something else for enjoyment which is win-win, is the preferable course of action, just as eating food that has a lower harm footprint is vs. eating meat.

This is apparently what Isaac thinks consequentialist morality looks like, in his perverted thought experiment:

- Don't do anything at all: 0

- Gang rape without roofies: -1,000,000 for the girl, + 50 for the men (10 each) = -999,950

- Gang rape with roofies (where the girl never knows, the men are very gentle, and she just has a worse hangover): -10 for the girl +50 for the men = +40

Isaac understands only that the second option isn't good, but he thinks it's OK to set up false dichotomies and consider anything "in the green" to be acceptable to consequentialists while ignoring better options:

- Don't do anything at all: 0