Difference between revisions of "Objective-subjective distinction"

(→Cornell Realism) |

(→Cornell Realism) |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

Cornell realism holds that moral properties such as right, wrong, good, bad etc. are natural properties but are not reducible to non-moral properties. | Cornell realism holds that moral properties such as right, wrong, good, bad etc. are natural properties but are not reducible to non-moral properties. | ||

| − | But first: what would it mean for moral properties to be natural properties if they are not reducible to non-moral properties? According to non-reductionists, moral properties ‘are constituted by’, or ‘are multiply realized by’, or ‘supervene upon’ non-moral properties, but they do not reduce to non-moral properties. | + | But first: what would it mean for moral properties to be natural properties if they are not reducible to non-moral properties? According to non-reductionists, moral properties ‘are constituted by’, or ‘are multiply realized by’, or ‘supervene upon’ non-moral properties, but they do not reduce to non-moral properties. To illustrate the difference consider the moral property of rightness: |

: ''We can imagine an indefinite number of ways in which actions can be morally right. [Non-reductionists] think that, in any one example of moral rightness, the rightness can be identified with non-moral properties (e.g. the handing over of money, the opening of a door for someone else, etc.). But they claim that, across all morally right actions, there is no one non-moral property or set of non-moral properties that all such situations have in common and to which moral rightness can be reduced. | : ''We can imagine an indefinite number of ways in which actions can be morally right. [Non-reductionists] think that, in any one example of moral rightness, the rightness can be identified with non-moral properties (e.g. the handing over of money, the opening of a door for someone else, etc.). But they claim that, across all morally right actions, there is no one non-moral property or set of non-moral properties that all such situations have in common and to which moral rightness can be reduced. | ||

'' | '' | ||

| − | For example, one might argue that certain natural kinds like | + | For example, one might argue that certain natural kinds like ‘intelligence’ or ‘organism’ are not obviously reducible to natural kinds in physics, and that mental types like being in pain is not necessarily reducible to neurological types like being in a state of C-fibre stimulation. |

Revision as of 07:37, 16 January 2018

Work In Progress.

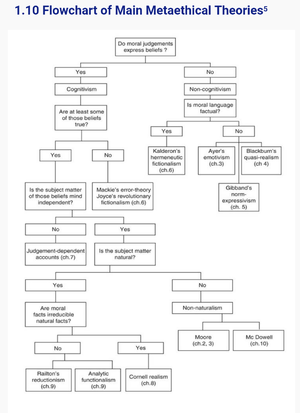

Objective morality is often the subject of straw-manning, whereby, it is claimed that moral objectivism purports the existence of the moral properties, such as rightness and wrongness, that exist independently of the natural properties of the world. This results from a misunderstanding of what objective morality means, and works against rational morality and moral discourse. In this article we will consider distinction between the well defined philosophical positions of moral universalism (moral objectivism) and moral relativism, and between moral realism and moral subjectivism. It's worth noting that due to the way these positions are defined, it is possible to have a subjectivist position that is also universal (objective), such as divine command theory. Whereby morality is universal (objective) and depends on a mind (the mind of God).

Contents

Moral Universalism vs Moral Relativism

The distinction between moral universalism and moral relativism, is that moral universalism holds that morality is universal, meaning that moral principles apply to everyone and apply everywhere. Put simply, what is wrong for me here and now is also wrong for you. Moral relativism, in contrast, holds that there are moral principles that do not apply to everyone or everywhere and are dependent on the opinions of a person (individualist subjectivism), culture (cultural subjectivism) or similar.

The dominant view in philosophy is that morality is universal. The primary argument in its favour holding that morality is by definition universal, and as a consequence, if a rule is not universal then it is not a moral rule. Proponents of this line of reasoning appeal to the traditional use and meaning of morality, such as that found in religions, whereby moral rules apply universally. Moreover moral universalism aligns with the commonsense perception that when discussing conflicting moral statements, e.g. ‘torturing children is good’ versus ‘torturing children is not good’, (uttered by two different individuals), only one of these assertions could possibly be right.

Moral Realism vs Moral Subjectivism

Moral realism and moral subjectivism are defined by commitments to the following theses (where proposition means a statement suitable for truth or falsity):

Moral realism

- moral statements express propositions

- some moral statements are true

- moral statements are true or false in virtue of mind-independent properties of the world

Moral subjectivism

- moral statements express propositions

- some moral statements are true

- moral statements are true or false in virtue of mind-dependent properties of the world

Now if we are going to commit to a form of moral universalism, we must either adopt moral realism or an ideal observer form of subjectivism. Where an ideal observer theory, is a theory in which the moral actions are determined by an ideal observer such as a God, or a fictional ideally rational agent.

Consensus

There is no overwhelming consensus in moral philosophy, however according to a survey by philpapers [1] most philosophers subscribe to a form of moral realism.

Naturalistic Realism

Naturalistic realism refers to moral realist theories in which moral properties such as right and wrong refer to natural properties, such as well-being. These are split into two main categories, theories in which moral properties are reducible to natural properties and ones where they are not (i.e. where moral properties are irreducible to natural properties.). In the following sections we will describe the leading contemporarys views of Railton realism (reducible) and Cornell realism (irreducible).

Railton Realism

Cornell Realism

Cornell realism holds that moral properties such as right, wrong, good, bad etc. are natural properties but are not reducible to non-moral properties.

But first: what would it mean for moral properties to be natural properties if they are not reducible to non-moral properties? According to non-reductionists, moral properties ‘are constituted by’, or ‘are multiply realized by’, or ‘supervene upon’ non-moral properties, but they do not reduce to non-moral properties. To illustrate the difference consider the moral property of rightness:

- We can imagine an indefinite number of ways in which actions can be morally right. [Non-reductionists] think that, in any one example of moral rightness, the rightness can be identified with non-moral properties (e.g. the handing over of money, the opening of a door for someone else, etc.). But they claim that, across all morally right actions, there is no one non-moral property or set of non-moral properties that all such situations have in common and to which moral rightness can be reduced.

For example, one might argue that certain natural kinds like ‘intelligence’ or ‘organism’ are not obviously reducible to natural kinds in physics, and that mental types like being in pain is not necessarily reducible to neurological types like being in a state of C-fibre stimulation.